Effect of Smart Pill Box on Improving Adherence to 6-Mercaptopurine Maintenance Therapy in Pediatric ALL

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025; 46(03): 297-304

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0044-1790580

Abstract

Introduction 6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) forms the backbone of maintenance chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). A Children's Oncology Group study found 3.9-fold increased risk of relapse in children with 6-MP adherence less than 90%.

Objective This article estimates the impact of smart pill box in improving adherence to 6-MP during maintenance phase chemotherapy in children with ALL.

Materials and Methods It is a prospective interventional study done at pediatric oncology clinic of a tertiary care hospital. Participants being 40 newly diagnosed children with ALL. Baseline adherence was assessed and impact of smart pill box was estimated after using it for 60 days. Subjective and objective assessment of baseline adherence and adherence after intervention was done by subjecting the parents of the children to Morisky Medication Adherence Score 8 (MMAS-8) and measurement of patient's red blood cells (RBC) 6-MP metabolites (6-thioguanine [TGN] and 6-methylmercaptopurine [MMP]) levels, respectively, pre- and postintervention.

Results The mean age was 7.39 ± 4.29 years. NUDT15*3 polymorphism was present in 10.26%, and none had TPMT polymorphism. Baseline assessment of adherence to 6-MP by MMAS-8 revealed low, medium, and high adherence in 7.5, 35, and 57.5%, respectively. Baseline 6-TGN and 6-MMP levels by cluster analysis revealed poor adherence in 10%. Following intervention, mean MMAS-8 improved from 7.34 ± 0.78 to 7.66 ± 0.55 (p-value < 0.015) and the median 6-TGN level improved from 150 to 253 pmol/8 × 108 RBCs (p-value < 0.001).

Conclusion Nonadherence to 6-MP is widely prevalent in Indian children. Simple measures like smart pill box can improve adherence.

Keywords

ALL - maintenance chemotherapy - adherence - smart pill box - 6MP metabolitesPatient Consent

Informed patient consent was obtained for this study.

Supplementary MaterialPublication History

Article published online:

30 September 2024

© 2024. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Patients’ Adherence in the Maintenance Therapy of Children and Adolescents with Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaK. Kremeike, Journal of Pediatric Biochemistry, 2015

- Clinical implication of thiopurine methyltransferase polymorphism in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A preliminary Egyptian studyFarida H. El-Rashedy, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2015

- Cystic FibrosisJohn R McArdle, Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2009

- Cystic FibrosisJohn R McArdle, Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 2009

- Rehabilitation after Distal Radius Fractures: Opportunities for ImprovementHenriëtte A.W. Meijer, Journal of Wrist Surgery

- Improving Pneumococcal Vaccination Rates in an Inpatient Pediatric Diabetic Population<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- A Metaanalysis of Interventions to Improve Adherence to Lipid-Lowering Medication<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Pediatric Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Louisiana: Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities for Enhanced Quality of Care<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Emerging issues in the management of infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Celiac disease in the ‘nonclassic’ patient<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

Abstract

Introduction 6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) forms the backbone of maintenance chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). A Children's Oncology Group study found 3.9-fold increased risk of relapse in children with 6-MP adherence less than 90%.

Objective This article estimates the impact of smart pill box in improving adherence to 6-MP during maintenance phase chemotherapy in children with ALL.

Materials and Methods It is a prospective interventional study done at pediatric oncology clinic of a tertiary care hospital. Participants being 40 newly diagnosed children with ALL. Baseline adherence was assessed and impact of smart pill box was estimated after using it for 60 days. Subjective and objective assessment of baseline adherence and adherence after intervention was done by subjecting the parents of the children to Morisky Medication Adherence Score 8 (MMAS-8) and measurement of patient's red blood cells (RBC) 6-MP metabolites (6-thioguanine [TGN] and 6-methylmercaptopurine [MMP]) levels, respectively, pre- and postintervention.

Results The mean age was 7.39 ± 4.29 years. NUDT15*3 polymorphism was present in 10.26%, and none had TPMT polymorphism. Baseline assessment of adherence to 6-MP by MMAS-8 revealed low, medium, and high adherence in 7.5, 35, and 57.5%, respectively. Baseline 6-TGN and 6-MMP levels by cluster analysis revealed poor adherence in 10%. Following intervention, mean MMAS-8 improved from 7.34 ± 0.78 to 7.66 ± 0.55 (p-value < 0.015) and the median 6-TGN level improved from 150 to 253 pmol/8 × 108 RBCs (p-value < 0.001).

Conclusion Nonadherence to 6-MP is widely prevalent in Indian children. Simple measures like smart pill box can improve adherence.

Keywords

ALL - maintenance chemotherapy - adherence - smart pill box - 6MP metabolitesIntroduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is among the most common malignancies in children. Cure rates vary between the risk groups and in developed countries cure rates are up to 90%-in low-risk group.[1] [2] [3] [4] Maintenance chemotherapy of 2 to 2.5 years of duration is an essential component of the treatment to achieve long-term disease-free remission in ALL.[5] [6] [7] Daily oral 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and weekly methotrexate administration form the backbone of maintenance chemotherapy.[6] Similar to other conditions requiring chronic oral intake of medications, nonadherence to 6-MP is frequently reported in children with ALL.[8] [9] Moreover, children are asymptomatic during maintenance phase which may further increase chances of nonadherence. Nonadherence to 6-MP puts them at increased risk of relapse. Indeed, a Children's Oncology Group (COG) study by Bhatia et.al found 3.9-fold increased risk of relapse in children with less than 90%-adherence.[8] This increased relapse risk has greater significance in the context of resource-limited setting as observed in most low-and-middle income countries (LMICs), as children with relapsed ALL have very poor access to intensive and novel therapy required for the cure.[10] Lack of adherence to 6-MP has been studied in children with ALL from developed countries.[9] Yet, little is known about its prevalence in LMICs.

Adherence to 6-MP can be measured by various methods including pill count, smart monitoring system, parent and/or child self-report, or therapeutic drug monitoring.[11] 6-MP has short half-life of 1.5 hours.[8] Hence, 6-MP level is not useful for therapeutic monitoring. However, 6-MP metabolites 6-thioguanine (6-TGN) and 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) accumulate in red blood cells (RBCs) over 1 to 3 weeks and monitoring 6-MP metabolite level is a good objective marker of long-term adherence.[11] Using a single cutoff value of active metabolite 6-TGN may not be helpful as there is a lot of variability in its level even among children with wild-type TPMT and NUDT15 genotype.[12] Hierarchical cluster analysis of RBC 6-MP metabolite level has been shown as good method for picking up children with poor adherence.[13] It is recommended that both objective and subjective methods should be used to better assess adherence to 6-MP.[8] [9] In this first study from India, we aimed to estimate prevalence of nonadherence to 6-MP in children with ALL by using both subjective and objective methods. We also aimed to study the effect of simple intervention like use of smart pill box in improving adherence to 6-MP during maintenance phase chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective interventional study conducted in the pediatric oncology clinic of a tertiary care hospital, over a duration of 1 year, after obtaining ethical clearance from the institutional review board.

Participants

A total of 40 newly diagnosed children with ALL between 0 and 18 years of age, who had completed at least 1 month of maintenance chemotherapy according to the Indian Collaborative Childhood Leukemia protocol were enrolled in the study, after taking informed consent from their parents and assent from children more than 12 years. The children who had received blood transfusion in the 2 months prior to the enrollment, or those in whom 6-MP was withheld for more than 5 days due to 6-MP-related toxicities, were excluded from the study. Clinical, demographic, and laboratory data, which included complete blood count and liver function test of the recruited children, were noted and TPMT and NUDT15 mutation analysis was done by gene sequencing for mutant alleles as per standard guidelines.[14]

Assessment of Adherence to 6-MP

Adherence was assessed first by the subjective method by Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8).[15] Parents of the subjects were interviewed as per the questionnaire in MMAS-8 ([Annuexure 2, 3] and [5], available in the online version). The total score range on the MMAS-8 was 0 to 8. Children with scores of more than 7.2, between 6 and 7.2 and less than 6 were classified as having high, medium, and low adherence, respectively.[8] Following this, objective assessment of adherence was done by cluster analysis of RBC 6-MP metabolites, 6-TGN, and 6 MMP.[16] [17] Briefly, 4 mL blood was collected from each patient and RBCs were cryopreserved at –80°C until analysis of 6-TGN and 6-MMP by mass spectroscopy. Cryopreserved packed RBCs were suspended in 500 µL in peripheral blood smear, and 250 µL of the solution was dispensed into a 1.5-mL microfuge tube. The hydrolysis and extraction process were performed as follows: diluted RBC solution (250 µL) was mixed with 20 µL of isotonic saline, 20 µL of 1.1 M dithiothreitol, and 50 µL of distilled water, vortexed for 30 seconds, and spun down. Then, 34 µL of 70% -perchloric acid was added, vortexed for 30 seconds, and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 minutes at room temperature. The supernatant (220 µL) was transferred to another polypropylene tube and hydrolyzed at 100°C for 1 hour. After cooling at room temperature, the acidic solution was neutralized with 220 µL of sodium hydroxide. Then, 50 µL of this solution was transferred to 1.5 mL of microfuge tube and dried using Speed Vacuum (Thermofisher Scientific, Cat. No. SPD1030-230) at low energy for 30 to 35 minutes. Samples pellets were then resuspended using 50 µL methanol:water (1:1, water:methanol) mixture for injection. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis was performed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography chromatographic system combined with a Q Exactive mass spectrometer fitted with a heated electrospray source operated in the positive ion mode. The software interface was Xcalibur 4.2, SII 1.3, and MSTune 2.8 SP1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Breda, The Netherlands). The levels of 6-TGN and 6-MMP in the samples were calculated on the basis of comparison of peak intensities with that of the internal standards.[18]

Intervention

Parents and children more than 10 years of age were educated regarding adherence to 6-MP and they were provided with I-store medicine storage box (smart pill box) with inbuilt alarm for a duration of 60 days. The smart pill box had a display for time with a facility to schedule three alarm timings and four compartments to keep the medications. This alarm box acted as a reminder for the patients to take the medication at the scheduled time. For assessment of the impact of intervention, the patients were again subjected to subjective and objective measurement of adherence by MMAS-8 and 6-MP metabolite level measurement as described before.

Primary Outcomes

To estimate the prevalence of nonadherence to 6-MP in maintenance phase chemotherapy and assess the impact of smart pill box as simple cost-effective intervention for improving adherence to 6-MP in maintenance phase chemotherapy in pediatric ALL.

Primary Outcomes

To estimate the prevalence of nonadherence to 6-MP in maintenance phase chemotherapy and assess the impact of smart pill box as simple cost-effective intervention for improving adherence to 6-MP in maintenance phase chemotherapy in pediatric ALL.

Secondary Outcomes

To assess effectiveness of MMAS-8 as a subjective method for assessing adherence and its correlation with the objective method of estimating drug metabolite levels.

To look for NUDT and TPMT polymorphism in children with ALL and there correlation with the metabolite levels.

To study the factors affecting adherence in children with ALL.

Inclusion Criteria

Newly diagnosed children with ALL who had completed at least 1 month of maintenance chemotherapy.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients in last 3 months of maintenance phase.

Patients for whom 6-MP was withheld for more than 5 days by treating physician due to any reason during previous 1 month.

Patients who received RBC transfusion in the last 90 days.

Children with relapsed ALL.

Patients not consenting for the study.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was carried out by mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables, frequency, and proportion for categorical variables. Categorical outcomes were compared between study groups using the chi-square test and/or Fisher's exact test. Categorical variables at different time periods of follow-up were compared using the McNamar test; reported frequencies and proportions along with p-values. For normally distributed quantitative parameters, the mean values were compared between study groups using independent sample t-test (two groups). The change in the quantitative parameters, before and after the intervention was assessed by paired t-test. For normally distributed quantitative parameters, the mean values were compared between study groups using analysis of variance. For nonnormally distributed quantitative parameters, medians and interquartile range (IQR) were compared between study groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. The change in the quantitative parameters, before and after the intervention was assessed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. For nonnormally distributed quantitative parameters, medians and IQR were compared between study groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Two numerical parameters (6-TGN and 6-MMP levels) were used to perform cluster analysis by hierarchical agglomerative method. Cluster 1 were characterized by very low levels (above 20th percentile of cutoff point) of 6-TGN levels and 6-MMP levels and these were considered to be nonadherent and other three clusters were considered adherent. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS version 22 was used for statistical analysis. The mean score of MMAS-8 were calculated and the pre- and postintervention mean scores were compared by using the chi-square test. The hierarchical cluster analysis of drug metabolite concentrations was done and the pre- and postintervention levels were compared. Correlation between MMAS-8 and metabolite levels was done and p-value was calculated.

Ethical Approval

IEC, JNMC, Belgaum; No. MDC/DOME/161 dated January 25, 2021. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Results

A total of 40 children with ALL in complete remission 1 (CR1), who had completed at least 1 month of maintenance phase of chemotherapy were enrolled in the study. The mean age was 7.39 ± 4.29 years and male-to-female ratio was 1.5:1. B-cell ALL was the most common immunophenotype of ALL accounting for 87.50%-of the cases. As per the National Cancer Institute risk stratification, 55%-belonged to standard risk and 45%-to high risk. As far as distribution of patients in different maintenance cycle was concerned, 32.50, 20.00, 5.00, 10.00, 15.00, 7.50, and 10%-belonged to M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, M6, and M7 number of maintenance cycles, respectively. Evaluation of NUDT15 and TPMT polymorphisms revealed presence of NUDT15*3 polymorphism in heterozygous state in 4 out of 39 (10.26%) patients, and none had TPMT polymorphism ([Table 5]).

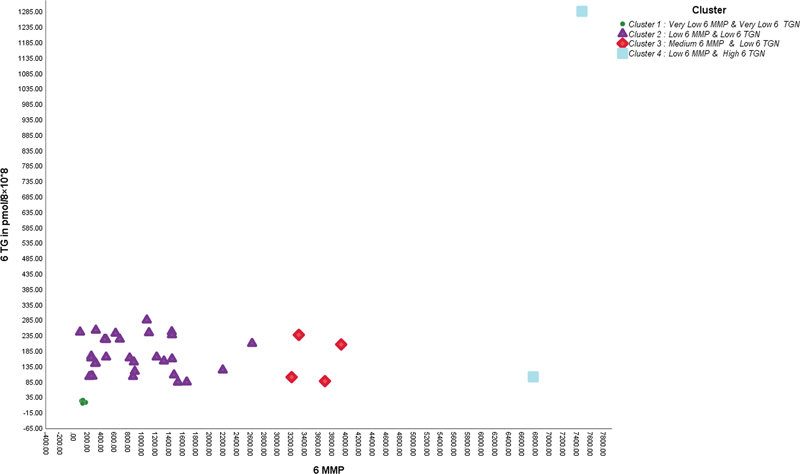

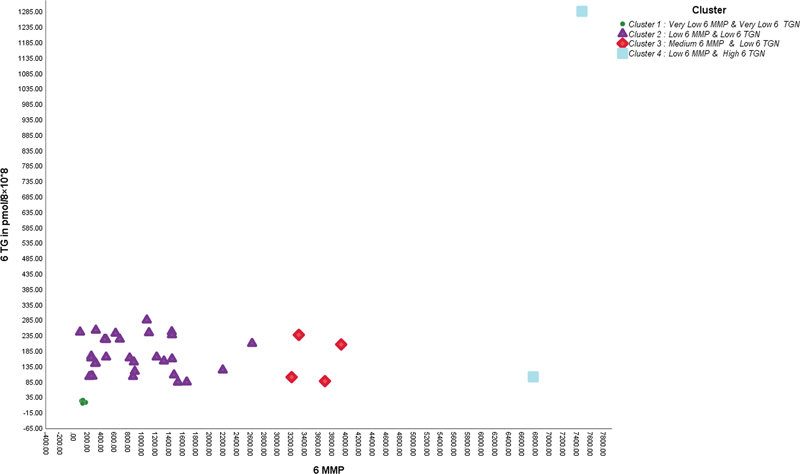

The baseline subjective assessment of adherence to 6-MP by MMAS-8 revealed that 3 children (7.5%) had low adherence, 17 (42.5%) had medium adherence, and 20 (50%) had high adherence ([Table 1]). Objective assessment of baseline adherence was done by quantifying 6-TGN and 6MMP levels and subjecting them to cluster analysis. Cluster 1 consisted of those with very low 6-MMP and very low 6-TGN levels, cluster 2 included those with low 6-MMP and low 6-TGN, cluster 3 consisted of those with medium 6-MMP and low 6-TGN, and cluster 4 included those with low 6-MMP and high 6-TGN levels ([Fig. 1]). Cluster analysis revealed that 4 (10%) had very low 6-TGN and 6-MMP levels reflecting poor adherence ([Fig. 2]). The baseline mean MMAS-8 score was 7.34 ± 0.78 and the baseline median 6-TGN and 6-MMP levels were 150 (100, 221) and 879 (270, 1528) pmol/8 × 108 RBCs, respectively. There was no statistically significant association of baseline adherence with patient- or parent-related factors ([Table 2]).

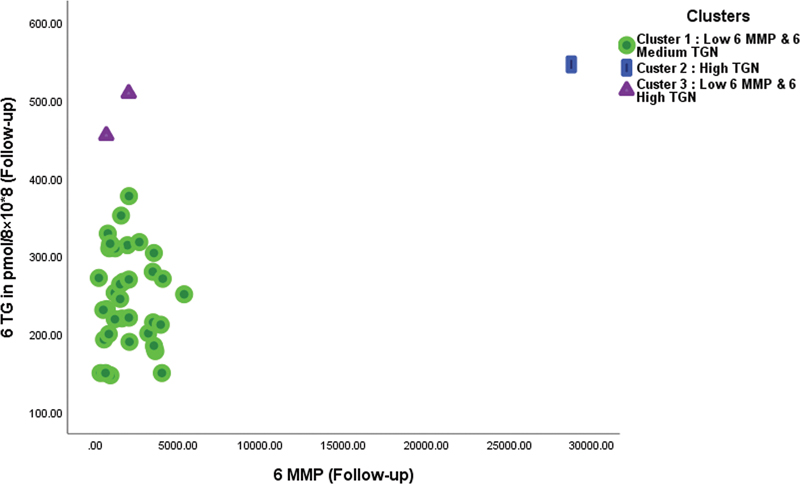

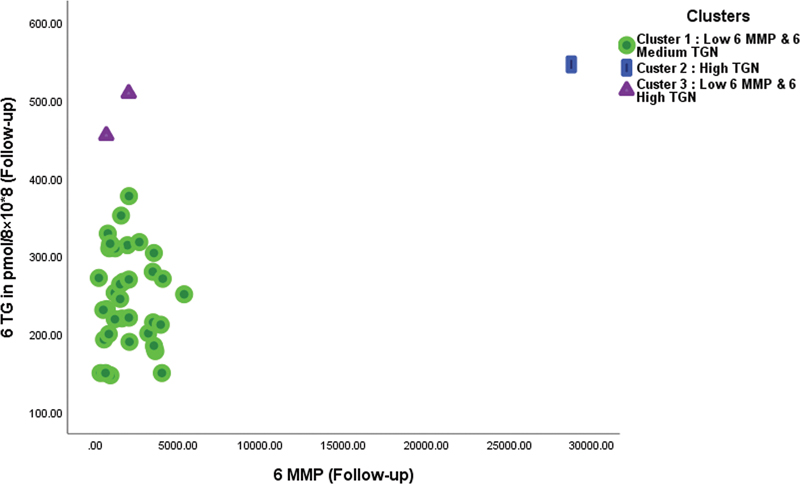

| Fig 1 : Scatter plot showing the clusters for 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TGN) follow-up levels.

| Figure 2: Scatter plot showing the clusters for 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TGN) baseline levels.

|

MMAS-8 |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

High adherence (> 7.2) |

20 |

50 |

|

Medium adherence (6–7.2) |

17 |

42.50 |

|

Low adherence (< 6> |

3 |

7.50 |

|

Parameter |

MMAS-8 baseline |

Chi-square value |

p-Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

High adherence(N = 20) |

Medium adherence(N = 17) |

Low adherence(N = 3) |

|||

|

Gender |

|||||

|

Male |

11 (55.00%) |

10 (58.82%) |

3 (100.00%) |

− |

* |

|

Female |

9 (45.00%) |

7 (41.18%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

Number of siblings |

|||||

|

Zero |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (11.76%) |

0 (0.00%) |

− |

* |

|

One |

11 (55.00%) |

9 (52.94%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

Two |

6 (30.00%) |

5 (29.41%) |

3 (100.00%) |

||

|

Three |

3 (15.00%) |

1 (5.88%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

Socioeconomic status (as per modified B.G. Prasad classification[30]) |

|||||

|

I |

3 (15.00%) |

1 (5.88%) |

0 (0.00%) |

− |

* |

|

II |

2 (10.00%) |

3 (17.65%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

III |

4 (20.00%) |

3 (17.65%) |

1 (33.33%) |

||

|

IV |

2 (10.00%) |

7 (41.18%) |

2 (66.67%) |

||

|

V |

9 (45.00%) |

3 (17.65%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

Type of family |

|||||

|

Joint |

9 (45.00%) |

6 (35.29%) |

2 (66.67%) |

1.13 |

0.5686 |

|

Nuclear |

11 (55.00%) |

11 (64.71%) |

1 (33.33%) |

||

|

Education (mother) |

|||||

|

No formal education |

3 (15.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

Primary education |

2 (10.00%) |

6 (35.29%) |

2 (66.67%) |

− |

* |

|

Secondary education |

11 (55.00%) |

9 (52.94%) |

1 (33.33%) |

||

|

Graduate |

4 (20.00%) |

2 (11.76%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

Postgraduate |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

||

|

Education (father) |

|||||

|

No formal education |

3 (15.00%) |

1 (6.25%) |

0 (0.00%) |

− |

* |

|

Primary education |

3 (15.00%) |

3 (18.75%) |

1 (33.33%) |

||

|

Secondary education |

7 (35.00%) |

9 (56.25%) |

1 (33.33%) |

||

|

Graduate |

7 (35.00%) |

2 (12.50%) |

1 (33.33%) |

||

|

Postgraduate |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (6.25%) |

0 (0.00%) |

||

|

MMAS-8 (follow-up) |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

High adherence |

26 |

65.00 |

|

Medium adherence |

14 |

35.00 |

|

Parameter |

Mean ± SD |

Mean difference |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Morisky scale parent score (N = 40) |

|||

|

Baseline |

7.34 ± 0.78 |

–0.32 |

0.015 |

|

Follow-up |

7.66 ± 0.55 |

||

|

6-TGN in pmol/8 × 108 RBC |

Median (interquartile range) |

Wilcoxon's sign rank test statistics |

p -Value |

|

Baseline |

150 (121) |

–4.80 |

< 0> |

|

Follow-up |

253 (114) |

||

|

6-MMP in pmol/8 × 108 RBC |

|||

|

Baseline |

879 (1258) |

–3.82 |

< 0> |

|

Follow-up |

1678 (2593) |

|

Parameter |

NUDT mutation (mean ± SD) |

p-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Positive (N = 4) |

Negative (N = 35) |

||

|

6-TGN in pmol/8 × 10*8 (baseline) |

177.25 ± 42.95 |

220.21 ± 252.87 |

0.739 |

|

6-MMP (baseline) |

499.75 ± 262.27 |

1670.64 ± 1719.99 |

0.187 |

References

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

30 September 2024

© 2024. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Patients’ Adherence in the Maintenance Therapy of Children and Adolescents with Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaK. Kremeike, Journal of Pediatric Biochemistry, 2015

- Clinical implication of thiopurine methyltransferase polymorphism in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A preliminary Egyptian studyFarida H. El-Rashedy, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2015

- Cystic FibrosisJohn R McArdle, Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2009

- Cystic FibrosisJohn R McArdle, Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 2009

- Rehabilitation after Distal Radius Fractures: Opportunities for ImprovementHenriëtte A.W. Meijer, Journal of Wrist Surgery

- Improving documentation of oral chemotherapy doses in a pediatric oncology clinic<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- A Video Game Improves Behavioral Outcomes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer: A Randomized Trial<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- The 2020 Focused Updates to the NIH Asthma Management Guidelines: Key Points for Pediatricians<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Medicine Won’t Work if It Isn’t Taken<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Health Care Provider-Delivered Adherence Promotion Interventions: A Meta-Analysis<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

| Fig 1 : Scatter plot showing the clusters for 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TGN) follow-up levels.

| Figure 2: Scatter plot showing the clusters for 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TGN) baseline levels.

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share