Epigenetics

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2020; 41(03): 378-380

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_24_20

Abstract

Historically, cancer is known to be a genetic disease. It is now realized that it involves epigenetic abnormalities along with genetic alterations. Epigenetics is an extra layer of instruction that lies upon DNA and controls how the genes are read and expressed. It simply means changes in phenotype without a change in genotype. In this review we aim to discuss the fundamentals of epigenetics, role of these alterations in carcinogenesis and its implications for epigenetic therapies.

Publication History

Received: 26 January 2020

Accepted: 27 May 2020

Article published online:

28 June 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Historically, cancer is known to be a genetic disease. It is now realized that it involves epigenetic abnormalities along with genetic alterations. Epigenetics is an extra layer of instruction that lies upon DNA and controls how the genes are read and expressed. It simply means changes in phenotype without a change in genotype. In this review we aim to discuss the fundamentals of epigenetics, role of these alterations in carcinogenesis and its implications for epigenetic therapies.

Introduction

Darwin's theory of evolution is driven by genetic variation and natural selection, whereas Lamarck's theory is based on the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Conrad Waddington explained these concepts and coined the term epigenetics in 1942, to illustrate the interactions between genes and the environment. The term “Epi” comes from the Greek word meaning “upon or above.” Therefore, epigenetics is an extra layer of instruction that lies upon DNA and controls how the genes are read and expressed. This explains why, despite having same genetic code, cells from different tissues behave differently and also the fact that identical twins are not actually identical!

Epigenetic changes alter gene expression or phenotype without changing the primary DNA sequence and are heritable.[1] Their implications include normal development, disease pathophysiology (including cancers), and therapies for cancer. In contrast to genetic alterations, epigenetic changes are relatively stable and reversible.

Cancer Epigenetics

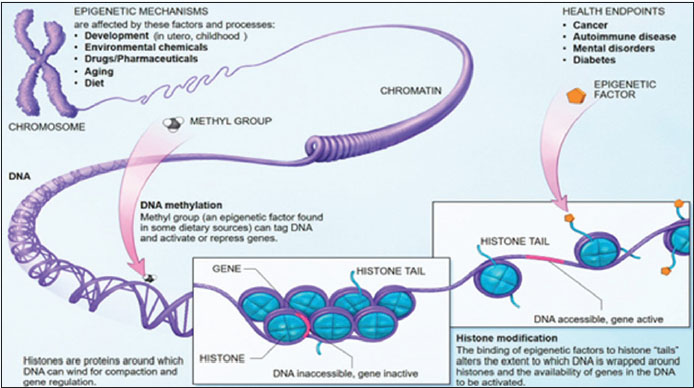

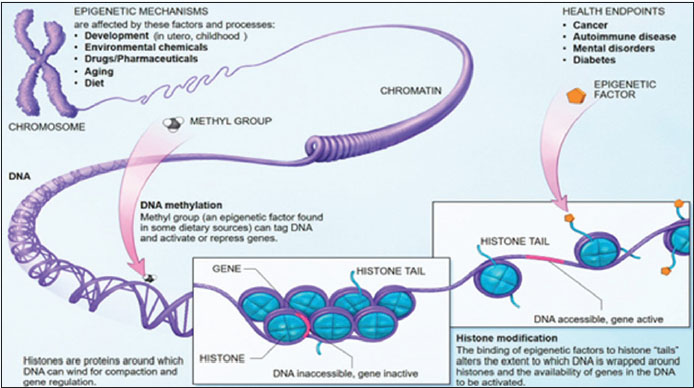

Broadly, epigenetic information falls into three categories: DNA methylation, histone modification, and microRNA (and chromatin) regulation.

Epigenetic modifications involve either covalent attachment (or removal) of a methyl or acetyl group to a DNA base or a histone (DNA-binding proteins), leading to DNA methylation of promoter region (CpG island) and histone modification,[2] which inactivate selected tumor suppressor genes causing loss of expression [Figure 1].[3] DNA methylation is the best understood epigenetic modification for several reasons as it can be copied, interpreted, and erased as required. It is stable over a period of decades making it the most useful epigenetic marker. Histone methylation differs from DNA methylation as the methyl groups are added to lysine and arginine, instead of cytosine and guanine pairs of DNA.

| Figure 1:Epigenetic mechanisms

MiRNAs are small noncoding RNAs of 19–25 nucleotides that bind to the areas on target mRNAs and affect gene expression by inhibiting the translation of the specific mRNA. MiRNAs are implicated in the carcinogenesis of APL and many solid tumors.

Few examples of common epigenetic signatures include:

-

Global hypomethylation, e.g., hypomethylation of RAS oncogenes

-

Promoter hypermethylation, e.g., CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer

-

Inactivation of VHL gene in RCC by hypermethylation of VHL promoter

-

Mutations affecting the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) in malignant gliomas and AML

-

Hematologic malignancies:

-

Mutations in genes that control histone modifications - MLL, EZH2

-

Mutations in genes that control DNA methylation - TET2, IDH1, IDH2, and DNMT3

-

Mutations in genes that control nucleosome position - SNF5, ARID1A.

-

Techniques Used for Studying or Detecting Epigenetic Changes

Various techniques used for studying epigenetics have been summaries in [Table 1].[4]{Table 1}

|

Epigenetic techniques |

Tools for studying |

|---|---|

|

PCR – Polymerase chain reaction; qPCR – Quantitative PCR; ChIP – Chromatin immunoprecipitation; 3C – Chromosome conformation capture; NGS – Next generation sequencing |

|

|

1. DNA methylation analysis |

|

|

Bisulfite conversion |

PCR, qPCR, and sequencing |

|

High-resolution melt analysis |

PCR |

|

Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation |

DNA microarrays or NGS |

|

2. Analysis of DNA/histone |

|

|

ChIP |

PCR, qPCR, sequencing, and microarray hybridization |

|

3. Chromatin accessibility and conformation assays |

|

|

EpiQ™ chromatin analysis kit |

PCR, qPCR |

|

Digital DNase and DNase Seq |

NGS |

|

3C |

PCR |

| Figure 1:Epigenetic mechanisms

References

- Feinberg AP. The key role of epigenetics in human disease prevention and mitigation. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1323-34

- Füllgrabe J, Kavanagh E, Joseph B. Histone onco-modifications. Oncogene 2011; 30: 3391-403

- National Institutes of Health. Available from: http://commonfund.nih.gov/epigenomics/figure.aspx. [Last accessed 2020 May 30].

- Hamamoto R, Komatsu M, Takasawa K, Asada K, Kaneko S. Epigenetics analysis and integrated analysis of multiomics data, including epigenetic data, using artificial intelligence in the era of precision medicine. Biomolecules 2019; 10 DOI: 10.3390/biom10010062.

- Gurion R, Vidal L, Gafter-Gvili A, Belnik Y, Yeshurun M, Raanani P. et al. 5-azacitidine prolongs overall survival in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica 2010; 95: 303-10

- Zagni C, Floresta G, Monciino G, Rescifina A. The search for potent, small-molecule HDACIs in cancer treatment: A decade after vorinostat. Med Res Rev 2017; 37: 1373-428

- Liu X, Gong Y. Isocitrate dehydrogenase inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Biomark Res 2019; 7: 22

- Dear AE. Epigenetic modulators and the new immunotherapies. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 684-6

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share