Guidelines for locoregional therapy in primary breast cancer in developing countries: The results of an expert panel at the 8 th Annual Women's Cancer Initiative - Tata Memorial Hospital (WCI-TMH) Conference

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2012; 33(02): 112-122

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.99748

Abstract

Background: Limited guidelines exist for breast cancer management in developing countries. In this context, the Women′s Cancer Initiative - Tata Memorial Hospital (WCI-TMH) organised its 8 th Annual Conference to update guidelines in breast cancer. Materials and Methods: Appropriately formulated guideline questions on each topic and subtopic in the surgical, radiation and systemic management of primary breast cancer were developed by the scientific committee and shared with the guest faculty of the Conference. Majority of the questions had multiple choice answers. The opinion of the audience, comprising academic and community oncologists, was electronically cumulated, followed by focussed presentations by eminent national and international experts on each topic. The guidelines were finally developed through an expert panel that voted on each guideline question after all talks had been delivered and audience opinion elicited. Separate panels were constituted for locoregional and systemic therapy in primary breast cancer. Results: Based on the voting results of the expert panel, guidelines for locoregional therapy of breast cancer have been formulated. Voting patterns for each question are reported. Conclusions: The updated guidelines on locoregional management of primary breast cancer in the context of developing countries are presented in this article. These recommendations have been designed to allow centers in the developing world to improve the quality of care for breast cancer patients.

Publication History

Article published online:

13 April 2022

© 2012. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background:

Limited guidelines exist for breast cancer management in developing countries. In this context, the Women's Cancer Initiative - Tata Memorial Hospital (WCI-TMH) organised its 8th Annual Conference to update guidelines in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods:

Appropriately formulated guideline questions on each topic and subtopic in the surgical, radiation and systemic management of primary breast cancer were developed by the scientific committee and shared with the guest faculty of the Conference. Majority of the questions had multiple choice answers. The opinion of the audience, comprising academic and community oncologists, was electronically cumulated, followed by focussed presentations by eminent national and international experts on each topic. The guidelines were finally developed through an expert panel that voted on each guideline question after all talks had been delivered and audience opinion elicited. Separate panels were constituted for locoregional and systemic therapy in primary breast cancer.

Results:

Based on the voting results of the expert panel, guidelines for locoregional therapy of breast cancer have been formulated. Voting patterns for each question are reported.

Conclusions:

The updated guidelines on locoregional management of primary breast cancer in the context of developing countries are presented in this article. These recommendations have been designed to allow centers in the developing world to improve the quality of care for breast cancer patients.

INTRODUCTION

A number of international guidelines currently exist in breast cancer, all aiming to ensure uniformity and quality in the delivery of care to patients with breast cancer.[1–4] The majority of guidelines have been developed in the context of evidence and clinical practice in the Western world. There is little representation from developing countries, if any, in the expert panels that formulate these guidelines. Clinical practice in developing countries, however, continues to be largely guided by these guidelines as they are based on high-quality evidence with expert appraisal. Many of these guidelines are not literally applicable to developing countries because of constraints on resources and/or expertise.

The Women's Cancer Initiative is a non-governmental organization that focuses on the cause of women's cancers. Women's Cancer Initiative – Tata Memorial Hospital – (WCI-TMH) has organized focussed theme-based Annual Breast and Gynecological Cancers Conferences for the past 8 years. This Conference invites and receives participation from national and international experts and academic and community oncologists from all disciplines. The Steering Committee of WCI-TMH decided, in view of the paucity of relevant guidelines, to commit the 2010 Annual Conference to the development of guidelines for the management of primary breast and cervical cancers in the express context of India and other developing countries. We report herein the results of the expert panel for the development of guidelines for locoregional therapy in primary breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The scientific committee of the Conference met over several sessions in the early part of 2010 to discuss the methodology for the development of these guidelines and important issues to be discussed. Members of the committee developed a series of appropriately formulated questions on each topic and subtopic in the surgical, radiation and systemic management of primary breast cancer. The majority of questions could be answered in the form of multiple choice answers, with the chosen answer amenable to formulation as a guideline, called the guideline questions.

It was decided that the best existing evidence on each question would be appraised in the Conference prior to the formulation of guidelines. It was decided to invite national and international experts to deliver focussed talks that will appraise the relevant evidence in the context of the previously decided questions. It was also decided that members of the audience would be invited to opine on the guideline questions through electronic voting prior to each talk. The final development of the guidelines would be done through an expert panel that will electronically vote on each guideline question after all talks had been delivered and audience opinion elicited. Although the majority of the panel time was to be allocated to voting, members of the panel would be allowed to make dissenting or consenting comments. Separate panels were constituted for locoregional and systemic therapy in primary breast cancer. This manuscript deals with the guidelines related to locoregional therapy in primary breast cancer.

RESULTS

The guideline questions (Appendix I) were developed and sent to the invited experts many months in advance of the Conference that was held from 22 to 24 October 2010. The experts were repeatedly reminded about the context of developing countries while preparing their presentations. The experts delivered talks that directly appraised the relevant evidence with respect to each question, preceded by audience voting on each of them. The expert panel on locoregional therapy convened and voted on the guideline questions on 22nd October 2010 after the completion of expert presentations and audience vote.

Pathology guidelines

Routine performance of HER2 testing in all breast tumors

The panel recommended (84% vs. 16%) that all breast tumors in developing countries be subjected to routine HER2 testing by immunohistochemistry (IHC). This was considered important for guiding the choice of systemic HER2-targeted therapy in primary breast cancer, if the latter was feasible. The panel also suggested that there was some prognostic and predictive capability (for anthracycline benefit) of HER2 testing.[5–7] In cases with a 2+ score on IHC, the panel advised performance of fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), if the latter capability is available at the institution/laboratory. The experts suggested that the American Society of Clincal Oncology and College of American Pathologists guidelines be followed in the performance of HER2 testing.[8]

Incorporation of multigene assays in clinical decision making

The expert panel voted (68% vs. 26%) against the routine incorporation of multigene assays like Recurrence Score (RS, Oncotype DX™) in clinical decision making, including prognostication and prediction of chemotherapy benefit. The panel considered the fact that RS had been shown to accurately prognosticate node-negative, hormone receptor-positive patients in retrospective validated analyses and to predict the benefit from chemotherapy in hormone receptor-positive patients, both in node-negative and node-positive situations.[9–11] However, the high cost and the current lack of prospective level 1 evidence for such tests weighed in the final decision of the majority of the panel. A minority of the panel members expressed the opinion that the use of such tests should be discussed with selected patients in developing countries based on financial feasibility.

Radiology guidelines

Local imaging prior to surgery – mammography and ultrasound

The panel voted (82% vs. 18%) for the routine use of both mammography and breast ultrasound in the evaluation of cases with early operable breast cancer. The panel agreed that the cornerstones of accurate local staging of breast cancer involved a good physical examination and bilateral mammography. The panel agreed that the addition of diagnostic breast ultrasound to mammography increases the accuracy and diagnostic yield, especially in patients with dense breasts and asymmetric densities in addition to providing image guidance for diagnostic procedures such as biopsies.[12]

Routine breast magnetic resonance imaging prior to breast conservation

The panel recommended against the routine use (89% vs. 11%) of breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to breast conservation therapy (BCT). The panel considered the randomized trial evidence that revealed a lack of benefit from routine pre-operative breast MRI and the relatively high rate of false positives with this technique.[13–16] The panel, however, also suggested that the use of breast MRI be considered in special situations like evaluation of dense breasts in very young women and in patients with lobular carcinomas.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography for routine staging in early and locally advanced breast cancer

The panel recommended against the routine use of PET and positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) (88% vs. 12%) for pre-treatment staging assessment of patients with early or locally advanced breast cancer. The panel considered the benefits of metabolic imaging, but the lack of good evidence for improvement in patient outcome measures and the possibility for confusion due to false-positive results weighed in its majority opinion. This recommendation is identical to the recent update in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for the use of PET-CT imaging.[1]

Surgical guidelines

Routine use of breast conserving therapy in developing countries

The panel voted in favor of offering breast conserving surgery to all eligible patients (88% vs. 12%) in developing countries. The panel noted that there was overwhelming evidence for the equivalent safety and efficacy of BCT compared with mastectomy in appropriately selected patients.[17,18] The panel considered the fact that tumors in these parts of the world are most often not screen detected, larger and there is variable availability of expertise for undertaking breast conservation.[19] However, the panel recommended that even in the latter situation, the option of BCT should at least be discussed with the patient, with the possibility of referral to centers that possess requisite expertise.

Importance of potential cosmetic outcome in decision making for BCT

The panel could not reach a majority verdict on the preference between a potentially cosmetically poor BCT and mastectomy (50% vs. 50%). The panel noted that number of patients and tumor and treatment-related factors are known to influence the cosmetic outcome after BCT,[20,21] and the fact that cosmesis could itself potentially affect physical, social, sexual and other domains in a patient's life. Some members discussed the element of subjectivity in evaluation of cosmesis, with patients sometimes rating their cosmesis better than the healthcare providers.

Separate incisions for primary and axillary surgery

The panel recommended that communication of the axillary dissection with the breast cavity be avoided as far as possible (78% vs. 22%) in order to prevent transfer of seroma fluid between these locations and to improve the cosmetic outcome. This is in agreement with the recommendations of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project.[22]

Use of oncoplastic procedures

The panel recommended (83% vs. 17%) that oncoplastic procedures be considered only in specialized centers with multidisciplinary expertise in these techniques. Oncoplastic surgery refers to techniques involving volume displacement and replacement in order to achieve superior cosmetic outcomes.[23–25] The panel noted that close cooperation among expert oncosurgeons, plastic surgeons, pathologists and radiation oncologists is required in order to achieve satisfactory cosmetic outcomes. The panel also suggested that surgical decisions like those on the type of incisions (linear versus quadrilateral), flap reconstruction and reduction mammoplasty could be important in achieving optimal results. The panel suggested that advanced centers with expertise could help to train individuals from developing countries in these techniques.

Defining adequacy of margins in primary breast surgery

The panel voted that the extent of margins after BCT was irrelevant as long as it was technically free (62% vs. 32%). A positive margin has often generated debate and controversy with respect to its significance related to local control rates and disease-free survival.[26–29] Guidelines have variously defined an adequate margin in breast conservation from 1 mm to 10 mm or more.[28–31] Interestingly, the rate of finding Invasive Ductal Carcinoma in the revised specimens has been in the range of only 30–40%.[32] Although there are conflicting reports, it is evident that obtaining a wide negative margin is desirable. However, a focally involved margin, particularly when re-excision is not technically feasible, as may be the case with a focally involved deep margin at the pectoralis fascia, is not a contraindication to planned therapy.

Management of positive posterior (chest wall) margin after mastectomy

The panel recommended (52% vs. 36%) that the posterior margin after an otherwise adequate mastectomy be revised wherever possible if it is reported to be grossly positive and if the area to be re-excised can be localized by the surgeon. Because this finding predicts for increased rates of local recurrence, all such patients should receive post-operative radiotherapy.[33,34]

Surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

The panel voted for marking the initial location and extent of tumor (94% vs. 6%) using techniques like biopsy scar, clips, tattoos, etc. in patients being planned for neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT). The panel noted that this facilitates ease of subsequent surgery and has a bearing on local control.[35,36]

The panel recommended (88% vs. 12%) that BCT is a valid option in selected cases of large or locally advanced breast cancer who achieve excellent response after NACT. The panel noted that this recommendation was not based on randomized level 1 evidence but on the low local recurrence rates in single-arm prospective series[37] and the non-randomized use of BCT in trials that evaluated NACT.[38] The panel also noted that there is likely to have been careful selection of good prognostic patients for post-NACT BCT in the latter reports and, therefore, similar selection be applied during routine use of this procedure in patients with large and locally advanced breast cancer.

Extent of post-NACT margins

The panel could not arrive at a majority decision (50% vs. 50%) on whether post-NACT BCT should be based on pre-chemotherapy or post-chemotherapy tumor volume. The panel noted that the administration of NACT often obscures the initial tumor size and makes planning of BCT difficult.[39,40] The panel also noted that some institutions have reported successful surgery based on post-chemotherapy tumor volume.[40]

Full axillary dissection as a routine standard of care

The panel recommended (59% vs. 41%) that a full axillary clearance that includes level III lymph nodes be undertaken as a standard procedure in breast cancer surgery in developing countries. The panel noted the relative abundance of large, non-screen-detected cancers and locally advanced breast cancers in these regions, with a high possibility of axillary nodal involvement being an important factor in this recommendation.[41] The panel also noted that there was high-quality evidence that the clearance of involved axillary lymph nodes improves overall survival.[42] The panel was cognizant of the reports that extensive axillary procedures could lead to increased incidence of adverse effects like shoulder stiffness and arm edema.[43,44]

Sentinel lymph node procedure and axillary sampling in breast cancer patients

The panel recommended (74% vs. 26%) that the sentinel lymph node technique could be considered in carefully selected patients with early breast cancer and clinically negative axilla in centers that have this expertise. The panel noted that there was now sufficient evidence regarding the oncological safety of this procedure from high-quality trials.[45,46] However, the panel recommended that in order to establish the safety of this procedure in developing countries, centers that undertake these procedures should regularly audit their outcome with adequate patient follow-up.

The panel recommended (54% vs. 46%) that anatomically defined sampling of lower-level axillary lymph nodes could be considered an alternative to the sentinel node technique. The boundaries of such a sampling would be intercostobrachial nerve cranially, insertion of lattisimus dorsi pedicle into the muscle caudally, chest wall medially and lateral border of lattisimus dorsi muscle laterally. Caveats for the sentinel technique, including those of careful patient selection and follow-up, apply to axillary sampling. The panel noted single-institution non-randomized reports of the safety of this procedure in selected patients.[47,48]

Depot hydroxyprogesterone prior to surgery for primary breast cancer

The panel voted against (65% vs. 35%) the adoption of pre-operative injection depot hydroxyprogesterone as a standard of care in patients with operable breast cancer. The panel acknowledged that a recently presented large randomized trial had suggested statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in disease-free and overall survival in patients with node-positive operable breast cancer with this intervention.[49] It also noted that a number of retrospective analyses had suggested improvements in outcome for surgery performed during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, although there had also been reports of no benefit.[50–52] The panel felt that the results would need to be published and replicated in other centers before pre-operative progesterone could be recommended as a routine standard of care.

Radiation therapy guidelines

Use of radiation in patients with one to three positive axillary nodes after mastectomy

The panel recommended (50% vs. 33%) that among post-mastectomy patients with one to three positive nodes, patients with additional poor risk features (young age, vessel invasion, inadequate axillary lymph node dissection) should receive radiotherapy This was based on the subgroup analysis from the Danish study that showed a survival benefit in these (one to three node positive) patients equivalent to those with more than three involved nodes involved and other studies that have tried to analyze specific risk factors in these patients.[53–56] The panel acknowledged that there is continuing controversy on the use of radiation in patients with one to three positive nodes.[55]

Benefit of modern radiation techniques in terms of local adverse effects and cosmesis

The panel voted (88% vs. 12%) in favor of newer radiation techniques (like three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D CRT), intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)) for achievement of better cosmesis and fewer local reactions when feasible and in specific situations.[57–59] The panel noted that larger breast sizes and left-sided breast cancer merited more careful planning and specialized radiotherapy techniques. On the question of the best technique for IMRT, the panel voted (60% vs. 40%) for forward planning IMRT as being the most suitable.

Use of Cobalt (Co) machines for radiation therapy after BCT and mastectomy

The panel voted (57% vs. 29%) that the Cobalt (Co)[60] machine could be used for post-BCT radiation in selected patients, especially in those with small breasts (interfield separation < 17 cm).[61] The panel considered the fact that cosmesis is an important outcome after BCT, and a number of radiation machine-related factors like beam energy and regional field separation play an important part in achievement of optimal outcomes.[21] The panel recognized that some studies have shown better cosmetic outcome for patients treated on linear accelerators compared with cobalt therapy units, especially in those with large breast size.[20] The panel also voted (62% vs. 38%) that the Co[60] unit was a valid option for radiotherapy after mastectomy when such treatment was indicated.

Adoption of hypofractionated radiation schedules as standard therapy

The panel initially voted in favor of hypofractionated radiotherapy (50% vs. 33%) based on recent reports of its equivalent efficacy in comparison with standard schedules in terms of local control and cosmesis.[62,63] However, some panellists expressed concern regarding the lack of long-term safety data (>10 years) with these techniques. After deliberation, the panel qualified its initial vote in favor of hypofractionated schedules, to state that such techniques be used only in centers with advanced simulation and planning systems.

Use of tumor bed boost after BCT

The panel recommended (50% vs. 33%) that tumor bed boost be given to all patients after whole breast radiotherapy, based on randomized evidence that its use improves local failure rates.[64] Radiotherapy boost after breast conservation can be given by various techniques including external beam conformal photon RT, interstitial implantation and use of electrons. As no technique has been shown to be better than others,[65] the panel recommended that any reasonable locally available technique could be used.

On the question of whether higher boost dose could compensate for the deleterious effect of a positive margin, the panel felt that this was not the case (50% vs. 43%).

Use of axillary nodal radiation after surgery

The panel voted (79% vs. 14%) for the omission of routine axillary radiation after adequate surgical clearance. This was primarily based on the low rates of axillary failure in such patients and the increased risk of arm edema and shoulder morbidity with the use of both modalities.[66–71] Thus, axillary radiation should be reserved for patients who have not undergone adequate axillary dissection.

Use of internal mammary radiation

The panel recommended (44% vs. 38%) that internal mammary radiation may be given only to a select group of breast cancer patients with adverse factors like large, inner quadrant tumors with heavy nodal burden that place them at higher risk of internal mammary nodal involvement. The panelists noted that a definitive European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer study has addressed this issue in a randomized design, and its results are expected soon. The panel also suggested that other factors such as pulmonary and cardiac comorbidities should be taken into account before delivering internal mammary radiation. Internal mammary lymphatics are relatively uncommon sites for recurrences, and radiation of this field is best omitted in patients with cardiac concerns, consistent with other guidelines.[71] The panel also noted a recent trial with 3 years follow-up that reported good tolerance to internal mammary radiation, including cardiac safety, but with higher rates of lung fibrosis and pneumonitis.[72]

Use of accelerated partial breast radiation

The panel voted (56% vs. 37%) for the use of (accelerated partial breast radiation (APBI) in a highly selected group of patients with low risk features (such as age >65 years, pathological tumor size < 2 cm and negative axillary nodes), which is consistent with the recent American Society of Therapeutic Radiation Oncology Guidelines.[79] There has been recent interest in using brachytherapy as the sole modality of radiation to decrease the treatment time and toxicities without compromising control.[73–77] The American Brachytherapy Society recommends a total dose of 34 Gy in 10 fractions to the clinical tumor volume and high dose rate brachytherapy is used as the sole modality.[78] The panel felt that considering present evidence, it is not possible to determine a subgroup of patients otherwise suitable for APBI who would not need any radiotherapy at all.

Follow-up of patients after primary treatment

Need for follow-up after primary treatment

The panel voted (67% vs. 33%) for the regular post-treatment follow-up of all patients with primary breast cancer. The panel recognized that there is lack of evidence from randomized trials supporting any particular follow-up sequence or protocol. The panel however felt that regular follow-up would help to ensure continuity of care, including early detection of local recurrences, contralateral breast cancer, management of therapy-related complications and facilitation of psychological support to enhance return to normal life after breast cancer.[80,81]

Use of investigative modalities during follow-up

The panel voted (67% vs. 33%) for annual mammogram as the only routinely required investigation during follow-up in patients who are asymptomatic and have a normal physical examination. This was based on evidence from two randomized trials that failed to prove any benefit from more extensive investigations during follow-up care.[82,83] The panel also suggested that the follow-up protocol could be institution based, and stressed the importance of good history taking and physical examination. Some panelists commented that the use of other investigations like imaging is occasionally useful in detecting early relapse in some patients.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

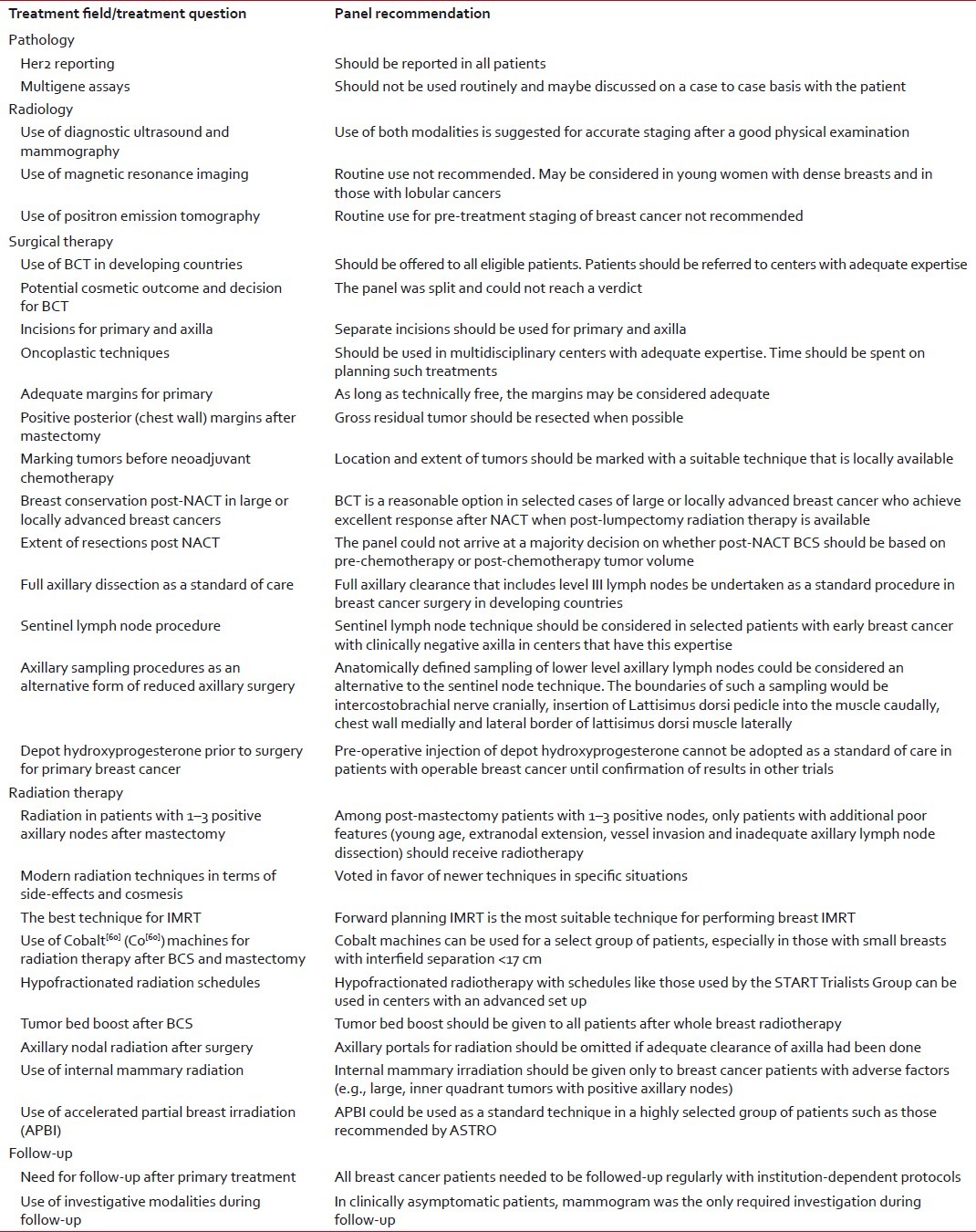

The development of evidence-based and effective breast cancer treatment techniques and guidelines is of great importance in developing countries. This is especially important for optimizing the efficacy of available therapies and early referral of selected patients to expert centers. The recommendations of the WCI-TMH Expert Panel have been summarized here. These recommendations have been designed to allow centers in the developing world to improve the quality of care for breast cancer patients. It needs to be noted that even though the guidelines are meant for developing countries, the bulk of evidence utilized for formulating these guidelines is generated from studies done in developed countries. Adoption of these guidelines and consistent collection of patient, disease, treatment and outcome data in developing countries would allow evaluation of the public health impact of guideline adherence in these regions [Table 1].

Table 1

Summary of the guidelines for developing countries for locoregional treatment of breast cancer

APPENDIX: GUIDELINE QUESTIONS

- Should Her2 be considered a standard in all histopathology reports?

- Is extent of margin for infiltrating ductal carcinoma irrelevant as long as the margin is technically free?

- Should gene profiling be pursued as a prognostic and predictive option?

- What imaging should patients of primary breast cancer ideally undergo?

- Should MRI be routinely done before surgery in patients undergoing breast conservation?

- Is PET CT a standard during work up for large and locally advanced breast cancer?

- Should BCT be offered as a standard to all eligible patients?

- Is a cosmetically poor BCT a preferable alternative to a mastectomy?

- Oncoplastic techniques in developing countries: 1) Should be used in all oncology centers, 2) Should be used only with good pathology, plastic and related services, 3) Do not know.

- Is level III clearance a must in routine practice of large and locally advanced cancers?

- Should communication with the breast cavity be avoided as far as possible during axillary dissection?

- Is sentinel lymph node biopsy a standard of care in a select group of breast cancer patients?

- Can axillary sampling be considered a preferred alternative to sentinel lymph node biopsy?

- Is there a role of sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

- Should we mark the initial tumor/tumor size in some way before giving neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

- Should the margin of resection in BCT after NACT be based on the initial lump size/clinical local findings?

- Should the margin of resection in BCT after NACT be based on the initial lump size?

- Is breast conservation a valid option for selected large and locally advanced breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

- Should margin-positive bases be reexcised after otherwise adequate mastectomy?

- Can solitary focal IDC margin positivity after breast conservation be safely ignored?

- Does surgery in a particular phase of ovulatory cycle affect outcome in breast cancer?

- Should administration of Proluton (hydroxyprogesterone) before surgery be considered a standard of care?

- Is cobalt machine an option in select group of patients post BCT?

- Can hypofractionated external beam radiotherapy be adopted as a standard of care at present?

- Which should be the preferred technique of doing whole breast IMRT?

- Should boost be given to all breast cancer patients who undergo conservation?

- Can a higher radiotherapy boost dose abrogate the effect of a positive margin?

- Is APBI a standard technique for a select group of patients?

- Would some patients suitable for APBI not need any radiotherapy at all?

- Regarding post-mastectomy, patients with 1–3 positive axillary nodes: 1) All should receive RT, 2)None should receive RT, 3)Only patients with additional poor features should receive RT, 4)Do not know.

- Is a cobalt machine as good as a linear accelerator for chest wall radiotherapy?

- Should axillary radiation be done after adequate axillary dissection in patients otherwise requiring post-operative radiotherapy?

- Should internal mammary radiation be given to breast cancer patients who are otherwise eligible for LRRT?

- Have modern radiotherapy machines improved local reactions and cosmetic outcome after breast conservation?

- Do we need to do any other investigation (besides a mammogram) in follow-up when patients are clinically asymptomatic?

- Do we need to regularly follow-up breast cancer cases?

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

Members of the Panel are listed at the end of manuscript. All members were present at the voting panel during the conference. The manuscript draft was sent to all the panellists for their approval. Dr. P K Julka was not present during the panel voting but gave his approval to the content of the manuscript. The authors of this manuscript want to thank the delegates of the 8th Tata Memorial Hospital - Women's Cancer Initiative (TMH-WCI) Conference for their contribution and useful comments.

Locoregional therapy consensus panel

- -R A Badwe, Director, Tata Memorial Center, Department of Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital

- -Benjamin Anderson: Professor and Director, Breast Health Clinic University of Washington/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Chair and Director Breast Health Global Initiative

- -Anurag Srivastava, Department of Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

- -Mandar Nadkarni: Head Breast Surgery at Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mumbai

- -Hemant Raj: Head, Department of Surgery, Apollo Hospital, Chennai, India

- -John Yarnold: Professor of Clinical Oncology, Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden Hospital, Surrey UK. (Representative of ESTRO at the conference)

- -P K Julka, Professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

- -Stephen Johnston, Professor, Department of Medical Oncology, Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton, UK

- -Sanjiv Sharma, Department of Radiation Oncology, Bangalore Institute of Oncology, Bangalore, India

- -Charlotte Coles, Department of Clinical Oncology, Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton, UK

- -Sangeeta Desai, Professor, Department of Pathology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

- -Vivek Kaushal, Professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, Medical College, Rohtak, India

- -Puneeta lal, Professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, SGPGI, Lucknow, India

- -G V Giri, Department of Radiation Oncology, Kidwai Institute, Bangalore, India

- -Seigo Nakamura, Professor, Department of Breast Surgical Oncology, Showa University, Japan

- -Indraneel Mittra, Professor Emeritus, Department of Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

- -S C Sharma, Professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India

- -Seema Medhi, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

- -Rakesh Jalali, Associate Professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

- -Nuran Bese, Professor in Radiation Oncology, Istanbul University, Cerrahpasa Medical School, Fatih Istanbul, Turkey

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share