Incidence and Trends of Breast and Cervical Cancers: A Joinpoint Regression Analysis

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2020; 41(05): 654-662

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_83_20

Abstract

Background: Breast and cervical cancers are two major cancers affecting women's health. Breast cancer is the most invasive cancer, and cervical cancer is the fourth most leading cause of death among women. Analysis of updated incidence data and their trends would help policymakers in planning and organizing programs to reduce the burden. This study aims to present regional variations in recent years and study trends of both the cancers in India. Materials and Methods: For recent incidence rates of cervical and breast cancers, data were obtained from the National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP) reports (2009–2011) for 25 registries and of 2012–2014 for 27 registries. Trends were studied for data obtained from different NCRP reports for the years 1982–2014 in six major registries. One in number of person who developed cancer and the annual Percentage change in incidence were calculated along with the trend analysis for both the cancers. The Joinpoint Regression Model was used for trend analysis. Results: The age-adjusted rate (AAR) of incidence of breast cancer in the South region was 36.78 in 2009–2011 as against the North region with 41 in 2012–2014. One in number who develop breast cancer remains highest in the North-East region but changed from 167 in 2009 to 200 in 2012. Cervical cancer was also the highest in the North-East region during 2009 and 2012. There is an increase in the overall cervical cancer incidence with 24.3 AAR in 2009 to 28.0 in 2012 and one in 200 who develop cervical cancer in 2009 to 250 in 2012. The trend analysis for six major registries showed an increase in the incidence of breast cancer, with the highest increase in New Delhi (3.22), and decrease in the incidence of cervical cancer, with the highest decrease in Mumbai (−1.21). Conclusion: There has been an exponential increasing trend in breast cancer and a steep declining linear trend in cervical cancer, conferring an inverse relationship between the two cancers. This trend is present in all the major cancer registries.

Keywords

Breast and cervical cancers - Joinpoint regression analysis - population-based cancer registry - trendsPublication History

Received: 27 February 2020

Accepted: 04 August 2020

Article published online:

17 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background: Breast and cervical cancers are two major cancers affecting women's health. Breast cancer is the most invasive cancer, and cervical cancer is the fourth most leading cause of death among women. Analysis of updated incidence data and their trends would help policymakers in planning and organizing programs to reduce the burden. This study aims to present regional variations in recent years and study trends of both the cancers in India. Materials and Methods: For recent incidence rates of cervical and breast cancers, data were obtained from the National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP) reports (2009–2011) for 25 registries and of 2012–2014 for 27 registries. Trends were studied for data obtained from different NCRP reports for the years 1982–2014 in six major registries. One in number of person who developed cancer and the annual Percentage change in incidence were calculated along with the trend analysis for both the cancers. The Joinpoint Regression Model was used for trend analysis. Results: The age-adjusted rate (AAR) of incidence of breast cancer in the South region was 36.78 in 2009–2011 as against the North region with 41 in 2012–2014. One in number who develop breast cancer remains highest in the North-East region but changed from 167 in 2009 to 200 in 2012. Cervical cancer was also the highest in the North-East region during 2009 and 2012. There is an increase in the overall cervical cancer incidence with 24.3 AAR in 2009 to 28.0 in 2012 and one in 200 who develop cervical cancer in 2009 to 250 in 2012. The trend analysis for six major registries showed an increase in the incidence of breast cancer, with the highest increase in New Delhi (3.22), and decrease in the incidence of cervical cancer, with the highest decrease in Mumbai (−1.21). Conclusion: There has been an exponential increasing trend in breast cancer and a steep declining linear trend in cervical cancer, conferring an inverse relationship between the two cancers. This trend is present in all the major cancer registries.

Keywords

Breast and cervical cancers - Joinpoint regression analysis - population-based cancer registry - trendsIntroduction

In India and other developing countries, breast and cervical cancers are the two leading types of cancer among women. Worldwide, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cause of death from cancer in women.[1] Cervical cancer is second only to breast cancer which affects 12% of all women.[2] As per the International Classification of Disease version 10 codes, breast and cervical cancers have C50 and C53 codes, respectively.[3]

According to the GLOBOCAN report 2018, breast cancer formed 11.6% of new cases of all new cancer cases globally with highest in Asia (43.6%).[4] The incidence of breast cancer varies greatly around the world: lowest in less-developed countries and highest in more-developed countries. Studies have shown that the greatest increase in the incidence rate of breast cancer by 2020 will be among women in developing countries, a majority of whom live in the Asian region.[5],[6] There has been a significant increase in the incidence rates since the 1970s, and is attributed to the modern lifestyle.[7],[8] In India, over 100,000 new cases of breast cancer are estimated to be diagnosed annually[9] with substantial differences in the incidence rates of breast cancer in rural (7–10/100,000) and urban (29–35/100,000) areas of India.[10]

According to the GLOBOCAN report 2018, cervical cancer observed 3.2% of new cases of all new cancer cases globally with highest in Asia (55.3%).[11] About 70% of cervical cancers and 90% of deaths due to cancer occur in developing countries.[12] It is due to poor cervical screening vaccination. In low-income countries, it is one of the most common causes of cancer death.[13] In developed countries, the widespread use of cervical screening programs has dramatically reduced the rates of cervical cancer.[14] In India, the number of people with cervical cancer is rising, but overall, the age-adjusted rates (AARs) are decreasing.

Various studies have reported the magnitude and trend of both the cancers separately and in combination.[15],[16],[17],[18],[19] As the data get updated time to time, repeat analysis of data using latest reports of PBCR is useful for knowing the current emerging picture of the disease status. A latest report by Asthana et al.[15] reported the incidences and trends of breast and cervical cancers up to 2008. Following this, no statement of analysis has been reported using incidence on these cancers that had been reported till 2014. Thus, this article aims to update the assessing trends in breast and cervical cancers from 1982 to 2014 which was reported by Indian cancer registries.

Materials and Methods

The National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP) with a network of population-based cancer registries (PBCRs) across India was started in 1982 which provides authentic data on the incidence and mortality of cancer in India for a defined period.

Data on the recent incidence rates for the present study were obtained from the published consolidated reports on 27 PBCRs for 2012–2014[20] and 25 PBCRs for 2009–2011[21] of NCRP of the Indian Council of Medical Research. The number of registries included for analysis in this article is calculated as per the data utilized in reports as mentioned. However, recently released reports, if any, providing data on new registries were not included in this article. The availability of data in different cities of the country depends on the year a particular registry came under the network of NCRP and/or initiation of the registry in a particular area. The report of 2009–2011 included data from four new registries (Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura, and Wardha). Three other PBCRs (Patiala, Naharlagun, and Patiala), which were included in the 2012–2014 report, were excluded from the 2009 to 2011 report because they just started collating data in that year. Data for cancer registries Chennai, Bengaluru, and Mumbai were available from 1982, whereas, for New Delhi, Bhopal, and Barshi cancer registries, the data were available from 1988. The PBCRs in various parts across the country were divided into six regions for the purpose of the present study, which are as follows: North: Delhi and Patiala; South: Bengaluru, Chennai, Kollam, and Thiruvananthapuram; Central: Bhopal; East: Kolkata; Northeast: Cachar district, Kamrup urban, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Sikkim, and Tripura; West: Mumbai, Nagpur, Pune, Ahmedabad, and Barshi extended. The regions were formed and presented by the authors and not by the original NCRP report.

Indicators such as crude rate (CR) and AAR were collected from the reports, and we computed another indicator named “one in number who develop cancer.” One out of the total number of persons who develop cancer was calculated as 100/cumulative risk, where cumulative risk = 100× (1 − exp [− cumulative rate/100])[20] and cumulative rate = (5× Σ[ASpR] × 100)/100,000; ASpR is the age-specific incidence rate. The cumulative risk is the probability that an individual will be diagnosed with cancer during a certain period in the absence of any competing cause of death and the assumption that the current trends will prevail over the period of time.[22] The age group of 0–64 years is used for computing lifetime cumulative risk.

Long-term trends of breast and cervical cancers in the six major registries (Chennai, Benagaluru, Mumbai, New Delhi, Barshi, and Bhopal) were collected for the years 1982–2014 and analyzed for trends (as per the availability of data in NCRP reports) using the Joinpoint Regression Model. The Joinpoint Regression Program is a statistical software developed by the National Cancer Institute for the analysis of trends using joinpoint models, that is, models where several different lines are connected together at the “joinpoints.”[23] The software takes trend data (e.g., cancer rates) and fits the simplest joinpoint model that the data allow. Analysis starts with the minimum number of joinpoint (i.e., 0 joinpoint, representing a straight line) and tests whether more joinpoints are statistically significant and must be added to the model (up to that maximum number). Joinpoint tests of significance use a Monte Carlo permutation method.[24] We used the Joinpoint Regression Programme version 4.7.0.0 to perform Joinpoint Regression Analysis.[25] It is available in open source. We also computed an annual percentage change (APC) in AAR for each line segment along with 95% confidence interval and P value. The APC was tested to determine whether there exists a difference from the null hypothesis of no change (0%) or not. This method was used to analyze the long-term trends of age-adjusted cancer incidence rates of breast and cervical cancers based on the published data from PBCR reports for six major registries.

Results

In [Table 1] and [Table 2], the incidence rates of breast and cervical cancers, from 2009 to 2014, are compared in six regions of the country. AAR of breast cancer was highest in the South region (25.78–36.65) in 2009–2011, whereas in 2012–2014, it was highest in the North region (33.13–41). The North-East region had the highest one in number who develop breast cancer in both the duration of 2009–2011 (42–167) and 2012–2014 (43–200).

Table 1 Crude rate, age-adjusted rate, and one in number who develop breast cancer

Table 2 Crude rate, age-adjusted rate, and one in number who develop cervical cancer

The North-East region had the highest burden of cervical cancer during 2009–2011 and 2012–2014. The AAR jumped from 5.62 to 24.33 in 2009 to 4.91 to 28.01 in 2012 with increase in one in number who develop cervical cancer from 4.91 to 28.01 in 2009 to 42 to 250 in 2012. [Table 2] states the risk of 42–250 for all regions in cervical cancer. This means one in 42 women in their lifetime is likely to develop cervical cancer to one in 250 in different regions as per the 2012–2014 incidence pattern. In this case, 42 (one in 42) is higher risk than 250 (one in 250).

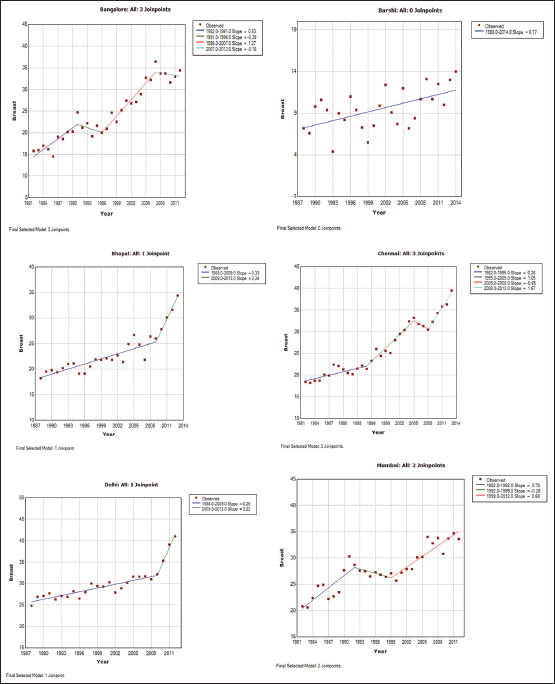

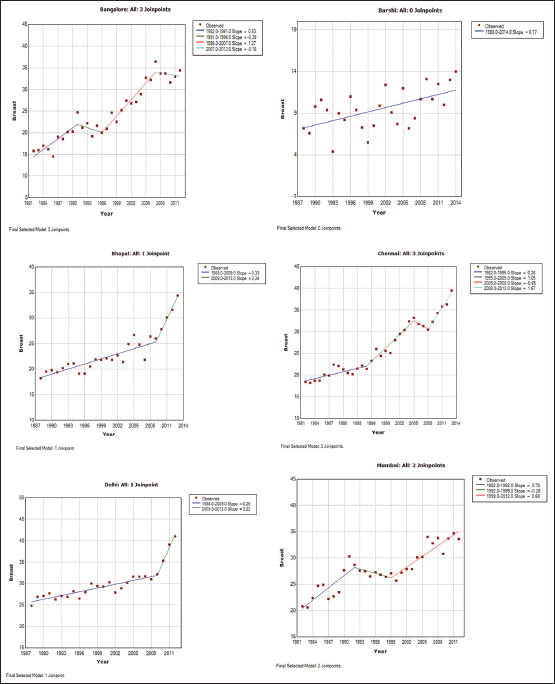

The Joinpoint regression procedures fitted the simplest joinpoint models for different duration slots of breast cancer data depending on the regression procedure, as shown in [Table 3]. [Table 4] and [Figure 1] show the joinpoint regression analysis in the six major registries, along with the APC for breast cancer. Chennai showed a positive trend with different APCs, except during 2005–2008. During these years, there was a negative trend with (−0.65) APC. Negative trends were seen in Bengaluru during 1991–1996 (−0.39) and 2007–2012 (−0.18). Mumbai showed a decrease in cases only in 1992–1999 with (−0.28) APC. New Delhi, Bhopal, and Barshi showed positive trends since enrollment. Delhi and Bhopal showed a drastic increase in the incidence rate of breast cancer during 2009–2012 (3.22) and 2009–2013 (2.24). Barshi showed a constant APC of 0.17 since 1988 till 2014.

| Figure 1: Breast cancer trends in major cancer registries by the Joinpoint regression analysis

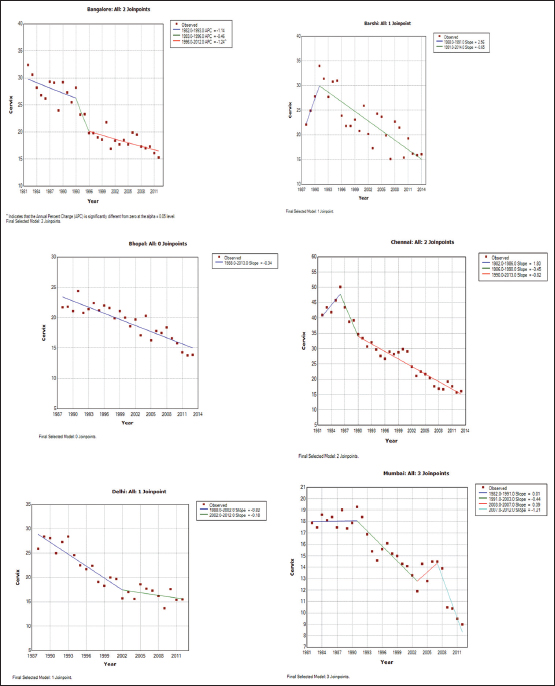

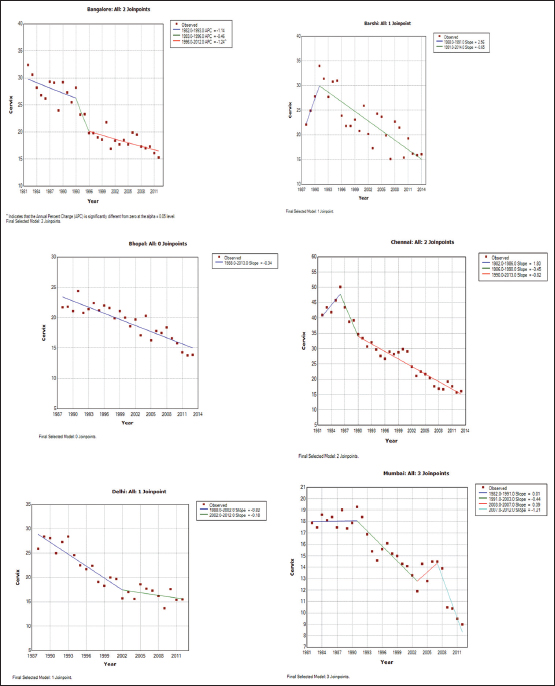

The Joinpoint regression procedures were fitted for different duration slots of cervical cancer data depending on the choice of procedure, as shown in [Table 5]. [Table 6] and [Figure 2] show the joinpoint regression analysis in the six major registries, along with the APC for cervical cancer. The registries showed contrasting trends for cervical cancer. Decline in incidence rates was observed in all the six major registries. Bengaluru, Delhi, and Bhopal showed negative trends since their enrollment in the NCRP, with the highest APC of −0.088 (1993–1996) for Bengaluru, −0.82 (1988–2012) for Delhi, and −0.34 (1988–2013) for Bhopal. Chennai and Barshi showed positive trends in the initial years, that is, 1982–1986, with 1.8 APC, and 1988–1991, with 2.56 APC, respectively, followed by a decrease in incidence. Although there is a decreasing trend over the period of 1982–2012, the jointpoints show a fluctuating trend in the individual time points. AAR was approximately constant during 1982–1991 (0.01) and was decreasing during 1991–2003 and 2007–2012 with −0.44 and −1.21 APC, respectively.

| Figure 2: Cervix cancer trends in major cancer registries by the Joinpoint regression analysis

Table 3Years’ data used for trend analysis along with different trends’ distribution for six major registries for breast cancer

|

Registry |

Years |

Trend 1 |

Trend 2 |

Trend 3 |

Trend 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chennai |

1982-2013 |

1982-1995 |

1995-2005 |

2005-2008 |

2008-2013 |

|

Bengaluru |

1982-2012 |

1982-1991 |

1991-1996 |

1996-2007 |

2007-2012 |

|

Mumbai |

1982-2012 |

1982-1992 |

1992-1999 |

1999-2012 |

|

|

New Delhi |

1988-2012 |

1988-2009 |

2009-2012 |

||

|

Bhopal |

1988-2013 |

1988-2009 |

2009-2013 |

||

|

Barshi |

1988-2014 |

1988-2014 |

Years’ data used for trend analysis along with different trends’ distribution for six major registries for cervical cancer

|

Registry |

Years |

Trend 1 |

Trend 2 |

Trend 3 |

Trend 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mumbai |

1982-2012 |

1982-1991 |

1991-2003 |

2003-2007 |

2007-2012 |

|

Chennai |

1982-2013 |

1982-1986 |

1986-1990 |

1990-2013 |

|

|

Bengaluru |

1982-2012 |

1982-1993 |

1993-1996 |

1996-2012 |

|

|

New Delhi |

1988-2012 |

1988-2002 |

2002-2012 |

||

|

Barshi |

1988-2014 |

1988-1991 |

1991-2014 |

||

|

Bhopal |

1988-2013 |

1988-2013 |

Discussion

The present study provided the updated and recently published data of incidence of breast and cervical cancers from last two NCRP reports, that is, 2009–2011 and 2012–2014, and reported the trends of these cancers in six major registries since 1982. The number of registries included for analysis in this article was as per the data utilized in reports as mentioned. However, recently released reports, if any, providing data on new registries, were not included in this article. This study presents the incidence of breast and cervical cancer update in 27 PBCRs in the recent years of 2009–2014 in the first instance. Our earlier study reported the incidence and trends of breast and cervical cancers up to 2008.[15] In addition, trends in the incidence rates of breast and cervical cancers were observed from 1982 to 2014 in six major registries. The burden of cervical cancer is highest in the North-East region in 2009 and 2012. The trend analysis for breast and cervical cancers in the major six registries gave unique and varying trends. The trend analysis using the joinpoint regression showed increasing/positive trends for breast cancer in all the six major registries, with the most significant increase in New Delhi, while Barshi showed constant increase since 1988. The Joinpoint regression analysis for cervical cancer showed overall decrease in the incidence rates in all the six major registries with a sharp decrease in Mumbai and Bhopal, which showed constant decrease in incidence rate since 1988.

Breast cancer is currently the most common cancer among women of all races and ethnicities. Furthermore, breast cancer represents the leading cause of cancer death among Latinas and the second leading cause among non-Hispanic, African - American, Asian - American/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native women.[26] Worldwide, breast cancer incidence has increased by over 20% since the GLOBOCAN 2008.[27],[28] This trend of increasing breast cancer incidence in the range of 4%–10% has also been observed in other countries that have transitioned from low income to middle income (such as the Philippines, Columbia, and Costa Rica) or from middle income to high income (such as Israel and the Czech Republic).[29],[30] According to the World Development Report of 1993, India's economic development has led to changes in diet and anthropometrics.[31] In India, the increase in incidence rate is attributable to lifestyle changes associated with higher economic development, such as women having fewer children and prolonged age at first birth and increased use of oral contraception.[32] Other lifestyle changes can also be due to increases in the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors, such as obesity and low levels of physical activity.[33]

There have been several explanations for the increase in the incidence rate of breast cancer. In 2001, Parkin et al. did a study to estimate the global burden of cancer. They postulated the adaptation of a Western lifestyle – an increased prevalence of ill-defined series of reproductive, hormonal, and dietary determinants in the population as a primary reason for the increasing breast cancer incidence rates observed among Asian and Asian-American women.[34] Bigby and Holmes in 2005 and Kurkure and Yeole in 2006 stated that the association between socioeconomic status and the risk of breast cancer is well established, with women in higher socioeconomic groups at a higher risk of breast cancer diagnosis relative to women with lower average social status.[35],[36] Explaining it further, Macmahon concluded that it was particularly among the higher socioeconomic classes with changing patterns of childbearing and breastfeeding (lower parity and reduced or no breastfeeding).[37] The relation between breast cancer incidence and factors such as diet, lifestyle, childbearing, and breastfeeding patterns was also explained by various other studies.[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43] They all had the same conclusions. Breast cancer patients are at a higher risk of developing cervical cancer among all other cancers because of shared hormonal effects.[44] Parkin et al.[45] reported that the incidence of breast cancer is higher among more affluent Western population. It is because of the changed dietary patterns, generally with increase in the consumption of meat, dairy products, vegetable oils, fruit juice, and alcoholic beverages and decrease in the consumption of starchy staple foods such as bread, potatoes, rice, and maize flour. Such dietary change was also reported in India. Considering lifestyle, one more study[46] emphasized on this aspect and reported that there is a notable reduction in physical activity and increase in obesity.

Various researchers have studied trend analysis for breast and cervical cancers for various time durations.[16],[17],[18],[47] An increased trend for the incidence of breast cancer across PBCRs was reported by Malvia et al. for 1982–2012[48] and Chaturvedi et al. for 1982–2010.[49] Badwe et al.,[50] Asthana et al.,[15] and Takiar and Srivastav[19] reported an increased trend in breast cancer and decrease in cervical cancer incidence in their trend analysis during their respective time periods. The American Cancer Society estimated cervical cancer statistics for 2019. According to the estimates, there will be 13,170 new cases of invasive cervical cancer and around 4250 women will die of cervical cancer in 2019.[51] In 2007, an analysis was done for the data of National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries, which showed the decrease of 6.7% in the incidence rate of breast cancer in 2003 as compared to 2002. The main reason of this decrease was said to be the discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy and was more common in women older or equal to 50 years of age.[52] The incidence and mortality rates of breast and cervical cancers were calculated in the Regional Health District of Barretos, São Paulo, Brazil. An increased incidence of both in situ and invasive breast cancer as well as a decrease in invasive cervical cancer was observed from 2000 to 2015. While in situ cervical cancer increased during the period, a reduction of cervical cancer mortality was observed. The reason attributing to these findings was said to be the breast and cervical cancer screening programs along with the access to the treatment.[53] Data from two cancer registries of Nigeria covering a 2-year period of 2009–2010 were analyzed, and it was concluded that there is a rise in the incidence rate of breast cancer but a relatively stable cervical cancer. The increase was attributed to improved diagnosis, better case finding, and improved access to care.[54] The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation did a systematic analysis for breast and cervical cancers in 187 countries from 1980 to 2010. They reported an increase in breast cancer from 1980 to 2010 at an annual rate of 3.1%, while the rate of increase in cervical cancer was 0.6%. They reported that the increased prevalence of risk factors is one of the reasons for this increase.[55]

The major advantage of this report is that we have consolidated and analyzed the data of NCRP regarding breast and cervical cancers since its establishment and also did a trend analysis using the joinpoint regression analysis for the six major registries. The Joinpoint regression analysis helped us in assessing the differential incidence pattern in these two cancers. NCRP annual reports contains updated and revised incidence data of the registries after following various rigorous checks on quality control. Although area and population covered by these registries are still small, it gives a fair idea of the extent to which cancer prevails in the country.

There is a need of combined studies on breast and cervical cancers because a causal relationship between human papillomavirus (HPV) and breast cancer has also been suggested,[56] and a review of twenty studies shows that nearly a quarter of breast carcinomas tested for HPV were of HPV positive.[57] Cervical precancer and breast cancer though share some common risk factors, such as hormonal contraceptive use,[58],[59] there are some studies which showed that there exists no relation between both cancers[60],[61],[62],[63],[64],[65] and some have proven the existence of a relationship between the two cancers.[66]

Conclusion

The present study concludes that there has been an exponential increasing trend in breast cancer and a steep declining linear trend in cervical cancer, conferring an inverse relationship between both breast and cervical cancers.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Cancer Report 2014. Ch. 5.12. World Health Organization; 2014. http://publications.iarc.fr/Non-Series-Publications/World-Cancer-Reports/World-Cancer-Report-2014. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- McGuire A, Brown JA, Malone C, McLaughlin R, Kerin MJ. Effects of age on the detection and management of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2015; 7: 908-29

- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. Three-year Report of Population Based Cancer Registries: 2009-2011: Report of 25 PBCRs in India. National Cancer Registry Programme and Indian Council Medical Research. http://www.ncdirindia.org/NCRP/ALL_NCRP_REPORTS/PBCR_REPORT_2009_2011/ALL_CONTENT/Main.htm. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- WHO. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/20-Breast-fact-sheet.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Khokhar A. Breast cancer in India: Where do we stand and where do we go?. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012; 13: 4861-6

- Anuar NS, Zahari SS, Taib IA, Rahman MT. Effect of green and ripe Carica papaya epicarp extracts on wound healing and during pregnancy. Food Chem Toxicol 2008; 46: 2384-9

- Laurance J. Breast Cancer Cases Rise 80% Since 1970s. Women Engage for a Common Future. https://www.wecf.eu/english/articles/2006/10/risks_breastcancer.php. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Imaginis Corporation. Breast Cancer: Statistics on Incidence, Survival, and Screening. https://www.imaginis.com/general-information-on-breast-cancer/breast-cancer-statistics-on-incidence-survival-and-screening-2. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Agarwal G, Pradeep PV, Aggarwal V, Yip CH, Cheung PS. Spectrum of breast cancer in Asian women. World J Surg 2007; 31: 1031-40

- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. Three-year report of population based cancer registries 2006-2008: Report of 20 PBCRs. National Cancer Registry Programme and Indian Council Medical Research. http://www.ncdirindia.org/All_. Available from: Reports/PBCR_2006_08/PBCR_2006_2008.pdf. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- WHO. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/23-Cervix-uteri-fact-sheet.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Saves Lives in the Republic of Korea. http://www9.who.int/features/2018/cervical-cancer-republic-of-korea/en/. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet No. 297: Cancer. https://www.scirp.org/((czeh2tfqyw2orz553k1w0r45))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=746327. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25].

- Canavan TP, Doshi NR. Cervical cancer. Am Fam Physician 2000; 61: 1369-76

- Asthana S, Chauhan S, Labani S. Breast and cervical cancer risk in India: An update. Indian J Public Health 2014; 58: 5-10

- Murthy NS, Agarwal UK, Chaudhry K, Saxena S. A study on time trends in incidence of breast cancer – Indian scenario. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007; 16: 185-6

- Murthy NS, Chaudhry K, Saxena S. Trends in cervical cancer incidence–Indian scenario. Eur J Cancer Prev 2005; 14: 513-8

- Dhillon PK, Yeole BB, Dikshit R, Kurkure AP, Bray F. Trends in breast, ovarian and cervical cancer incidence in Mumbai, India over a 30-year period, 1976-2005: An age-period-cohort analysis. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 723-30

- Takiar R, Srivastav A. Time trend in breast and cervix cancer of women in India-(1990-2003). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2008; 9: 777-80

- WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD 10). https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/II. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. Three-Year Report of Population Based Cancer Registries 2012-2014: Report of 27 PBCRs. National Cancer Registry Programme and Indian Council Medical Research. http://ncdirindia.org/All_Reports/PBCR_REPORT_2012_2014/ALL_CONTENT/Main.htm. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- National Cancer Registry Programme. Bangalore: Indian Council of Medical Research. Consolidated Report of the Population Based Cancer Registries 2001-2004. http://ncdirindia.org/NCRP/Rep1/PBCR_2001_2004.aspx. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software. Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000; 19: 335-51

- National Cancer Institute. Download Joinpoint Desktop Software. Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and population sciences. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/download. Available from: [Last acessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2009 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute; 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/uscs. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65: 87-108

- Bray F. Transitions in human development and the global Cancer burden. In: Wild CP. editor World Cancer Report 2014. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/28525/1/World Cancer Report.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Bray F, Jacques F. Age standardization. In: Forman D, Bray F, Brewster DH, Mbalawa CG, Kohler B, Piñeros M. et al., editors Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. IARC Scientific Publication No. 164. Vol. 10. Ch. 7. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5I-X/old/vol10/CI5vol10.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Forman D, Bray F, Brewster D, Mbalawa GC, Kohler B, Piñeros M. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. 10. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5I-X/old/vol10/CI5vol10.pdf. et al. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- World Bank. Invest in Health. World Development Report 1993. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993: 195-324 https://www.nap.edu/read/5513/chapter/4#15. Available from: [Last acessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Porter P. “Westernizing” women's risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 213-6

- Sylla BS, Wild CP. A million Africans a year dying from cancer by 2030: What can cancer research and control offer to the continent?. Int J Cancer 2012; 130: 245-50

- Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37 Suppl 8: S4-66

- Bigby J, Holmes MD. Disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Cancer Causes Control 2005; 16: 35-44

- Kurkure AP, Yeole BB. Social inequalities in cancer with special reference to South Asian countries. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006; 7: 36-40

- MacMahon B. Epidemiology and the causes of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 2373-8

- Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res 2004; 6: 229-39

- Korenman SG. Oestrogen window hypothesis of the aetiology of breast cancer. Lancet 1980; 1: 700-1

- Gao YT, Shu XO, Dai Q, Potter JD, Brinton LA, Wen W. et al. Association of menstrual and reproductive factors with breast cancer risk: Results from the Shanghai breast cancer study. Int J Cancer 2000; 87: 295-300

- Liu YT, Gao CM, Ding JH, Li SP, Cao HX, Wu JZ. et al. Physiological, reproductive factors and breast cancer risk in Jiangsu province of China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011; 12: 787-90

- Yanhua C, Geater A, You J, Li L, Shaoqiang Z, Chongsuvivatwong V. et al. Reproductive variables and risk of breast malignant and benign tumours in Yunnan province, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012; 13: 2179-84

- Bhadoria AS, Kapil U, Sareen N, Singh P. Reproductive factors and breast cancer: A case-control study in tertiary care hospital of North India. Indian J Cancer 2013; 50: 316-21

- Ewertz M, Jensen OM. Trends in the incidence of cancer of the corpus uteri in Denmark, 1943-1980. Am J Epidemiol 1984; 119: 725-32

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55: 74-108

- Key TJ, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC. The effect of diet on risk of cancer. Lancet 2002; 360: 861-8

- Yeole BB. Trends in cancer incidence in female breast, cervix uteri, corpus uteri, and ovary in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2008; 9: 119-22

- Malvia S, Bagadi SA, Dubey US, Saxena S. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Indian women. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017; 13: 289-95

- Chaturvedi M, Vaitheeswaran K, Satishkumar K, Das P, Stephen S, Nandakumar A. Time trends in breast cancer among Indian women population: An analysis of population based cancer registry data. Indian J Surg Oncol 2015; 6: 427-34

- Badwe RA, Dikshit R, Laversanne M, Bray F. Cancer incidence trends in India. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2014; 44: 401-7

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Cervical Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ. et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1670-4

- Da Costa AM, Hashim D, Fregnani JH, Weiderpass E. Overall survival and time trends in breast and cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the Regional Health District (RHD) of Barretos, São Paulo, Brazil. BMC Cancer 2018; 18: 1079

- Jedy-Agba E, Curado MP, Ogunbiyi O, Oga E, Fabowale T, Igbinoba F. et al. Cancer incidence in Nigeria: A report from population-based cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiol 2012; 36: e271-8

- Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. et al. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2011; 378: 1461-84

- Amarante MK, de Sousa Pereira N, Vitiello GA, Watanabe MA. Involvement of a mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) homologue in human breast cancer: Evidence for, against and possible causes of controversies. Microb Pathog 2019; 130: 283-94

- Li N, Bi X, Zhang Y, Zhao P, Zheng T, Dai M. Human papillomavirus infection and sporadic breast carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 126: 515-20

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Appleby P, Beral V, Berrington de González A, Colin D, Franceschi S. et al. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1609-21

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet 1996; 347: 1713-27

- Bjørge T, Hennig EM, Skare GB, Søreide O, Thoresen SO. Second primary cancers in patients with carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix. The Norwegian experience 1970-1992. Int J Cancer 1995; 62: 29-33

- Levi F, Randimbison L, Vecchia CL, Franceschi S. Incidence of invasive cancers following carcinoma in situ of the cervix. Br J Cancer 1996; 74: 1321-3

- Hemminki K, Dong C, Vaittinen P. Second primary cancer after in situ and invasive cervical cancer. Epidemiology 2000; 11: 457-61

- Evans HS, Newnham A, Hodgson SV, Møller H. Second primary cancers after cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III and invasive cervical cancer in Southeast England. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 90: 131-6

- Kalliala I, Anttila A, Pukkala E, Nieminen P. Risk of cervical and other cancers after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2005; 331: 1183-5

- Jakobsson M, Pukkala E, Paavonen J, Tapper AM, Gissler M. Cancer incidence among Finnish women with surgical treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, 1987-2006. Int J Cancer 2011; 128: 1187-91

- Hansen BT, Nygård M, Falk RS, Hofvind S. Breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ among women with prior squamous or glandular precancer in the cervix: A register-based study. Br J Cancer 2012; 107: 1451-3

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Received: 27 February 2020

Accepted: 04 August 2020

Article published online:

17 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Figure 1: Breast cancer trends in major cancer registries by the Joinpoint regression analysis

| Figure 2: Cervix cancer trends in major cancer registries by the Joinpoint regression analysis

References

- World Cancer Report 2014. Ch. 5.12. World Health Organization; 2014. http://publications.iarc.fr/Non-Series-Publications/World-Cancer-Reports/World-Cancer-Report-2014. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- McGuire A, Brown JA, Malone C, McLaughlin R, Kerin MJ. Effects of age on the detection and management of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2015; 7: 908-29

- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. Three-year Report of Population Based Cancer Registries: 2009-2011: Report of 25 PBCRs in India. National Cancer Registry Programme and Indian Council Medical Research. http://www.ncdirindia.org/NCRP/ALL_NCRP_REPORTS/PBCR_REPORT_2009_2011/ALL_CONTENT/Main.htm. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- WHO. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/20-Breast-fact-sheet.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Khokhar A. Breast cancer in India: Where do we stand and where do we go?. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012; 13: 4861-6

- Anuar NS, Zahari SS, Taib IA, Rahman MT. Effect of green and ripe Carica papaya epicarp extracts on wound healing and during pregnancy. Food Chem Toxicol 2008; 46: 2384-9

- Laurance J. Breast Cancer Cases Rise 80% Since 1970s. Women Engage for a Common Future. https://www.wecf.eu/english/articles/2006/10/risks_breastcancer.php. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Imaginis Corporation. Breast Cancer: Statistics on Incidence, Survival, and Screening. https://www.imaginis.com/general-information-on-breast-cancer/breast-cancer-statistics-on-incidence-survival-and-screening-2. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Agarwal G, Pradeep PV, Aggarwal V, Yip CH, Cheung PS. Spectrum of breast cancer in Asian women. World J Surg 2007; 31: 1031-40

- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. Three-year report of population based cancer registries 2006-2008: Report of 20 PBCRs. National Cancer Registry Programme and Indian Council Medical Research. http://www.ncdirindia.org/All_. Available from: Reports/PBCR_2006_08/PBCR_2006_2008.pdf. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- WHO. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/23-Cervix-uteri-fact-sheet.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Saves Lives in the Republic of Korea. http://www9.who.int/features/2018/cervical-cancer-republic-of-korea/en/. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet No. 297: Cancer. https://www.scirp.org/((czeh2tfqyw2orz553k1w0r45))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=746327. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25].

- Canavan TP, Doshi NR. Cervical cancer. Am Fam Physician 2000; 61: 1369-76

- Asthana S, Chauhan S, Labani S. Breast and cervical cancer risk in India: An update. Indian J Public Health 2014; 58: 5-10

- Murthy NS, Agarwal UK, Chaudhry K, Saxena S. A study on time trends in incidence of breast cancer – Indian scenario. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007; 16: 185-6

- Murthy NS, Chaudhry K, Saxena S. Trends in cervical cancer incidence–Indian scenario. Eur J Cancer Prev 2005; 14: 513-8

- Dhillon PK, Yeole BB, Dikshit R, Kurkure AP, Bray F. Trends in breast, ovarian and cervical cancer incidence in Mumbai, India over a 30-year period, 1976-2005: An age-period-cohort analysis. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 723-30

- Takiar R, Srivastav A. Time trend in breast and cervix cancer of women in India-(1990-2003). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2008; 9: 777-80

- WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD 10). https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/II. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. Three-Year Report of Population Based Cancer Registries 2012-2014: Report of 27 PBCRs. National Cancer Registry Programme and Indian Council Medical Research. http://ncdirindia.org/All_Reports/PBCR_REPORT_2012_2014/ALL_CONTENT/Main.htm. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- National Cancer Registry Programme. Bangalore: Indian Council of Medical Research. Consolidated Report of the Population Based Cancer Registries 2001-2004. http://ncdirindia.org/NCRP/Rep1/PBCR_2001_2004.aspx. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software. Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000; 19: 335-51

- National Cancer Institute. Download Joinpoint Desktop Software. Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and population sciences. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/download. Available from: [Last acessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2009 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute; 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/uscs. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65: 87-108

- Bray F. Transitions in human development and the global Cancer burden. In: Wild CP. editor World Cancer Report 2014. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/28525/1/World Cancer Report.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Bray F, Jacques F. Age standardization. In: Forman D, Bray F, Brewster DH, Mbalawa CG, Kohler B, Piñeros M. et al., editors Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. IARC Scientific Publication No. 164. Vol. 10. Ch. 7. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5I-X/old/vol10/CI5vol10.pdf. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Forman D, Bray F, Brewster D, Mbalawa GC, Kohler B, Piñeros M. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. 10. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5I-X/old/vol10/CI5vol10.pdf. et al. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- World Bank. Invest in Health. World Development Report 1993. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993: 195-324 https://www.nap.edu/read/5513/chapter/4#15. Available from: [Last acessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Porter P. “Westernizing” women's risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 213-6

- Sylla BS, Wild CP. A million Africans a year dying from cancer by 2030: What can cancer research and control offer to the continent?. Int J Cancer 2012; 130: 245-50

- Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37 Suppl 8: S4-66

- Bigby J, Holmes MD. Disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Cancer Causes Control 2005; 16: 35-44

- Kurkure AP, Yeole BB. Social inequalities in cancer with special reference to South Asian countries. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006; 7: 36-40

- MacMahon B. Epidemiology and the causes of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 2373-8

- Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res 2004; 6: 229-39

- Korenman SG. Oestrogen window hypothesis of the aetiology of breast cancer. Lancet 1980; 1: 700-1

- Gao YT, Shu XO, Dai Q, Potter JD, Brinton LA, Wen W. et al. Association of menstrual and reproductive factors with breast cancer risk: Results from the Shanghai breast cancer study. Int J Cancer 2000; 87: 295-300

- Liu YT, Gao CM, Ding JH, Li SP, Cao HX, Wu JZ. et al. Physiological, reproductive factors and breast cancer risk in Jiangsu province of China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011; 12: 787-90

- Yanhua C, Geater A, You J, Li L, Shaoqiang Z, Chongsuvivatwong V. et al. Reproductive variables and risk of breast malignant and benign tumours in Yunnan province, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012; 13: 2179-84

- Bhadoria AS, Kapil U, Sareen N, Singh P. Reproductive factors and breast cancer: A case-control study in tertiary care hospital of North India. Indian J Cancer 2013; 50: 316-21

- Ewertz M, Jensen OM. Trends in the incidence of cancer of the corpus uteri in Denmark, 1943-1980. Am J Epidemiol 1984; 119: 725-32

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55: 74-108

- Key TJ, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC. The effect of diet on risk of cancer. Lancet 2002; 360: 861-8

- Yeole BB. Trends in cancer incidence in female breast, cervix uteri, corpus uteri, and ovary in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2008; 9: 119-22

- Malvia S, Bagadi SA, Dubey US, Saxena S. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Indian women. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017; 13: 289-95

- Chaturvedi M, Vaitheeswaran K, Satishkumar K, Das P, Stephen S, Nandakumar A. Time trends in breast cancer among Indian women population: An analysis of population based cancer registry data. Indian J Surg Oncol 2015; 6: 427-34

- Badwe RA, Dikshit R, Laversanne M, Bray F. Cancer incidence trends in India. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2014; 44: 401-7

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Cervical Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 25]

- Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ. et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1670-4

- Da Costa AM, Hashim D, Fregnani JH, Weiderpass E. Overall survival and time trends in breast and cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the Regional Health District (RHD) of Barretos, São Paulo, Brazil. BMC Cancer 2018; 18: 1079

- Jedy-Agba E, Curado MP, Ogunbiyi O, Oga E, Fabowale T, Igbinoba F. et al. Cancer incidence in Nigeria: A report from population-based cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiol 2012; 36: e271-8

- Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. et al. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2011; 378: 1461-84

- Amarante MK, de Sousa Pereira N, Vitiello GA, Watanabe MA. Involvement of a mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) homologue in human breast cancer: Evidence for, against and possible causes of controversies. Microb Pathog 2019; 130: 283-94

- Li N, Bi X, Zhang Y, Zhao P, Zheng T, Dai M. Human papillomavirus infection and sporadic breast carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 126: 515-20

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Appleby P, Beral V, Berrington de González A, Colin D, Franceschi S. et al. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1609-21

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet 1996; 347: 1713-27

- Bjørge T, Hennig EM, Skare GB, Søreide O, Thoresen SO. Second primary cancers in patients with carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix. The Norwegian experience 1970-1992. Int J Cancer 1995; 62: 29-33

- Levi F, Randimbison L, Vecchia CL, Franceschi S. Incidence of invasive cancers following carcinoma in situ of the cervix. Br J Cancer 1996; 74: 1321-3

- Hemminki K, Dong C, Vaittinen P. Second primary cancer after in situ and invasive cervical cancer. Epidemiology 2000; 11: 457-61

- Evans HS, Newnham A, Hodgson SV, Møller H. Second primary cancers after cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III and invasive cervical cancer in Southeast England. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 90: 131-6

- Kalliala I, Anttila A, Pukkala E, Nieminen P. Risk of cervical and other cancers after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2005; 331: 1183-5

- Jakobsson M, Pukkala E, Paavonen J, Tapper AM, Gissler M. Cancer incidence among Finnish women with surgical treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, 1987-2006. Int J Cancer 2011; 128: 1187-91

- Hansen BT, Nygård M, Falk RS, Hofvind S. Breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ among women with prior squamous or glandular precancer in the cervix: A register-based study. Br J Cancer 2012; 107: 1451-3

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share