Management and Long-term Outcomes of Giant Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors in Children

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2019; 40(04): 515-520

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_80_18

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the study is to evaluate the outcome of children with giant mediastinal germ cell tumors (GCTs). Materials and Methods: A retrospective study of children diagnosed with GCTs treated at our hospital from 1998 to 2014 was performed. They were evaluated for their tumor size, malignancy, treatment, complications, and outcome. Results: Twelve giant mediastinal GCT patients were included in the study. Age ranged from 7 to 144 months (median 12 months) and all except one were males. The average tumor size was 10.4 cm (range 6 cm × 5 cm–16 cm × 13 cm) and in four patients, they were large enough to occupy nearly the entire hemithorax. Nine children had benign tumors, and these were resected upfront. The remaining three cases with malignant disease received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. No significant reduction in size was noticed in these patients, but alpha-fetoprotein levels decreased in all the three, and they were later resected. Eight (67%) were resected through posterolateral thoracotomy and 4 (33%) through median sternotomy approach. One patient had a dumbbell-shaped thoracoabdominal tumor extending through a Bochdalek hernia. He required additional laparotomy as well as diaphragmatic repair. There were no postoperative complications. The malignant GCTs received total four courses of PEB. All patients were alive and asymptomatic at a mean follow-up of 55.4 months (range 10–146 months). Conclusions: Mediastinal GCTs have bimodal age distribution and show male preponderance. Malignant mediastinal GCTs responded well to neoadjuvant chemotherapy through a reduction in size was not noticed. Complete excision often in coordination with cardiothoracic-vascular surgeons can lead to long-term symptom-free survival even in giant tumors.

Publication History

Received: 10 April 2018

Accepted: 18 October 2018

Article published online:

03 June 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the study is to evaluate the outcome of children with giant mediastinal germ cell tumors (GCTs). Materials and Methods: A retrospective study of children diagnosed with GCTs treated at our hospital from 1998 to 2014 was performed. They were evaluated for their tumor size, malignancy, treatment, complications, and outcome. Results: Twelve giant mediastinal GCT patients were included in the study. Age ranged from 7 to 144 months (median 12 months) and all except one were males. The average tumor size was 10.4 cm (range 6 cm × 5 cm–16 cm × 13 cm) and in four patients, they were large enough to occupy nearly the entire hemithorax. Nine children had benign tumors, and these were resected upfront. The remaining three cases with malignant disease received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. No significant reduction in size was noticed in these patients, but alpha-fetoprotein levels decreased in all the three, and they were later resected. Eight (67%) were resected through posterolateral thoracotomy and 4 (33%) through median sternotomy approach. One patient had a dumbbell-shaped thoracoabdominal tumor extending through a Bochdalek hernia. He required additional laparotomy as well as diaphragmatic repair. There were no postoperative complications. The malignant GCTs received total four courses of PEB. All patients were alive and asymptomatic at a mean follow-up of 55.4 months (range 10–146 months). Conclusions: Mediastinal GCTs have bimodal age distribution and show male preponderance. Malignant mediastinal GCTs responded well to neoadjuvant chemotherapy through a reduction in size was not noticed. Complete excision often in coordination with cardiothoracic-vascular surgeons can lead to long-term symptom-free survival even in giant tumors.

Introduction

Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors (GCTs) constitute 6%–18% of the pediatric mediastinal tumors.[1] [2] Only 3%–4% of GCTs are mediastinal in location.[3] Giant mediastinal GCTs defined as tumors measuring at least 5 cm × 4.5 cm on computed tomography (CT) scan, are even rarer.[4]

Most children present with prolonged noninfectious respiratory symptoms, chest pain, superior vena cava syndrome, or with nonspecific symptoms.[5] [6] [7] The treatment and clinical outcomes of mediastinal GCT depend on the age, histology, and the nature of malignancy of the tumor. Complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice.[8] [9] [10] [11] [12] The rarity of this tumor, its anatomical location and its varied histology pose a treatment challenge both to the oncologist and the surgeon. Localized disease, complete resection, and platinum-based chemotherapy are associated with improved survival in malignant mediastinal GCTs.[12] In this study, the importance of coordinated effort of the oncologist, pediatric surgeons, and cardiovascular surgeons in achieving complete tumor clearance is highlighted.

Materials and Methods

Prospectively, collected data of patients diagnosed with GCT enrolled at the pediatric surgery clinic of BRA Institute Rotary Cancer hospital at AIIMS were analyzed after taking ethical clearance. Patients with mediastinal GCTs operated from 1998 to 2014 were included. Patients had been evaluated on the basis of clinical symptoms, imaging chest X-ray, and contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) of the chest and tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein levels [αFP] and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin [βhCG]). A preoperative histological diagnosis was not done routinely. Well-demarcated lesions with calcifications or well-defined bony elements and heterogeneous attenuation, displacing rather than invading adjacent structures were diagnosed as GCTs. Three patients with doubtful radiology underwent biopsy. Patients with raised αFP were treated as high-risk malignant GCTs with 2/3 courses of PEB (cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin) as neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by reassessment and then surgical resection and subsequent completion of total four courses of PEB.

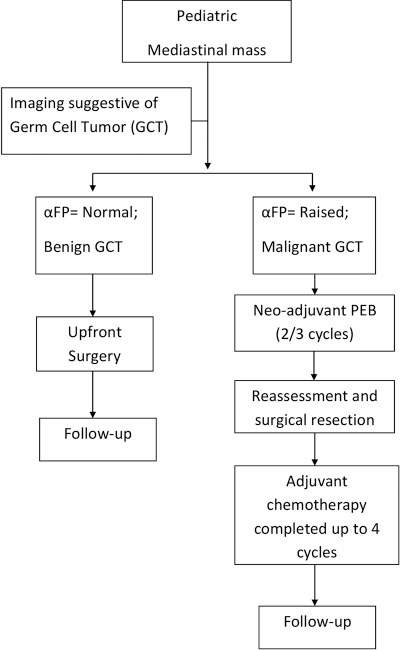

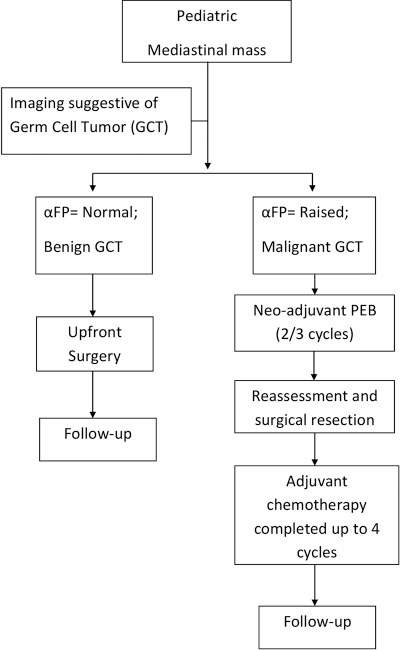

Those with tumors measuring more than 5 cm × 5 cm on imaging were labeled as giant GCTs. The demographic profile, clinical data, presenting symptoms, radiographic findings, biopsy reports, αFP levels, tumor location, tumor size, surgical approach, completeness of resection, tumor histology, chemotherapy, complications, and disease-related outcomes were evaluated. The surgical approach (thoracotomy vs. median sternotomy) was decided on the basis of the location of these tumors, size, tumor extension, infiltration into adjacent structures, and the choice of the surgeon. The follow-up was done by clinical evaluation of symptom assessment, imaging studies (X-rays and CECT chest), and tumor markers (αFP and βhCG). [Figure 1] summarizes the management protocol followed. The Kaplan–Meier estimates were applied to calculate overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS), where an event was either recurrence of the disease or death.

| Fig. 1 Management protocol followed for mediastinal germ cell tumors. GCT – Germ cell tumors; αFP – Alpha-fetoprotein; PEB – Cisplatin, Etoposide, and Bleomycin

Observations and Results

Totally, 12 children were included in the study. During 1998 through 2014, a total of 344 patients with GCTs (175 benign and 169 malignant) were treated at our center. Of these, 12 were mediastinal GCTs (3.5%), and all of these were giant GCTs. Their age ranged from 7 to 144 months (median 12 months). Of these, 5 (42%) were infants, 3 (25%) were 1–10 years old, and 4 (33%) children were older than 10 years of age. There were 11 (91.7%) males and 1 (8.3%) female. The children presented with symptoms of recurrent chest infections in 8 (42.1%), respiratory distress 5 (26.3%), chest pain 3 (15.7%), and chest mass 2 (10.5%). In one patient, the tumor was an incidental finding on radiologic imaging done for evaluating chest wall trauma.

Investigations

Investigations revealed that 3 (25%) children had very high αFP (>3 times as compared to normal for their age). They were treated as malignant GCT. Four had only mildly elevated αFP, and the rest five had normal levels as per age. These patients were managed as benign teratomas.

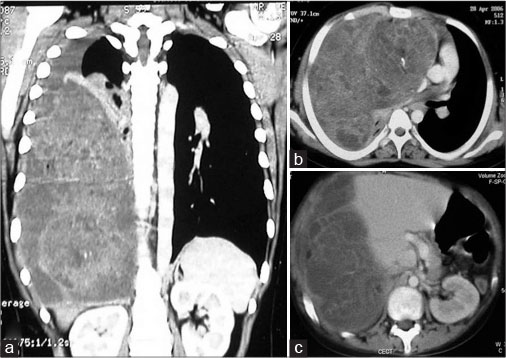

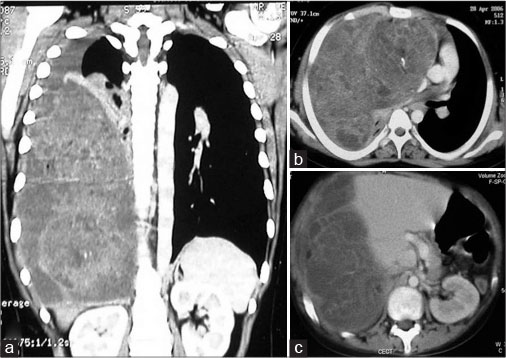

The tumor was located in the anterior mediastinum in 8 (66.7%) patients, left hemithorax in 2 (16.7%), and the right hemithorax in 1 (8.3%) [Figure 2]. In one of the patients, the tumor was located in the left posterior mediastinum and extended into the retroperitoneum through a Bochdalek hernia. In 2 (16.7%) of our patients, the tumor also involved the pericardium. Core needle biopsy was done in 4 (33.3%) patients where imaging was doubtful. Of them, 3 were reported as teratomas and 1 was inconclusive.

| Fig. 2 Computed tomography scan coronal (a) and axial sections (b and c) showing a Giant malignant germ cell tumors pushing the right dome of diaphragm down till the pelvis

Management

Nine patients, who were diagnosed with benign mediastinal teratoma, underwent upfront surgical resection. The 3 (25%) patients of malignant GCT received 2–3 courses of PEB neoadjuvant chemotherapy at 3 weekly intervals. On reassessment, a change in the tumor heterogeneity and decrease in αFP was noticed, but no significant decrease in size (>10% of original) was observed. In 5 (41.7%) patients left thoracotomy, in 4 (33.3%) median sternotomy, and in 3 (25%) right thoracotomy was the surgical approach. One of these tumors was placed in the left posterior mediastinum, and it extended into the retroperitoneum through a Bochdalek hernia. It was approached by a combined left posterolateral thoracotomy and a laparotomy. This dumbbell-shaped tumor had two globular masses measuring 16 cm × 13 cm × 7 cm (in the mediastinum) and 7 cm × 6 cm × 8 cm (in the abdomen) which were connected to each other through a thin stalk through the Bochdalek hernia.

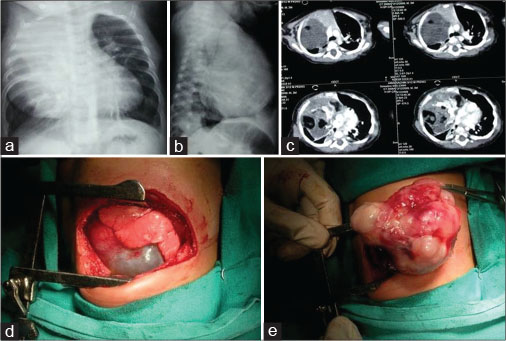

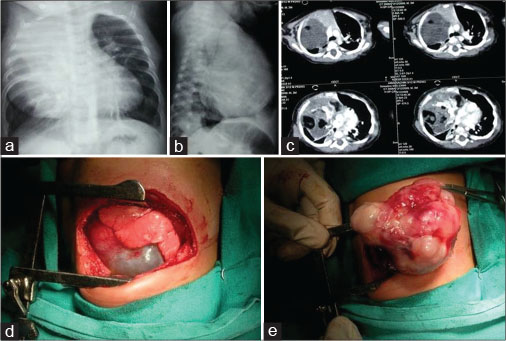

In 4 (33.3%) patients, a median sternotomy approach was used. Two of them had tumors located in the left hemithorax, and the other two had anterior mediastinal tumors. A 3-year-old boy with an 8 cm × 8 cm anterior mediastinal teratoma arising from the pericardium had sustained injury to the right bronchus and the diaphragm during excision, which were repaired after tumor removal. In a 10-year-old boy with anterior mediastinal GCT (7 cm × 7 cm × 6 cm) compressing the left lung, initially, a left thoracotomy had been attempted. The tumor could not be excised completely. A second attempt and complete excision of the tumor was done 2 years later by the median sternotomy approach with the help of cardiothoracic-vascular surgeons. The right thoracotomy was done in 3 (25%) patients and a complete tumor excision was achieved in all of them [Figure 3].

| Fig. 3 Chest X-ray anterior-posterior, lateral view (a and b) showing anterior mediastinal mass. (c) Computed tomography scan of the same patient with areas of calcification and fat in the tumor. (d and e) Right posterolateral thoracotomy and excision of the mass

The average tumor size on imaging was 10.2 cm × 10.4 cm and ranged from 5 cm × 6 cm to 16 cm × 13 cm. Older children had comparatively larger tumor sizes. On gross examination, the tumors were heterogeneous, lobulated with cystic and solid areas and occasional calcification. Operative histology revealed 9 (75%) to be mature teratomas and 3 (25%) to be immature teratomas. All these three immature teratomas had presented with markedly raised αFP confirming the presence of elements endodermal sinus tumors and so had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The raised αFP responded well to neoadjuvant PEB chemotherapy, but the size did not decrease significantly, and the postchemotherapy specimens were reported as immature teratomas.

Follow-up and outcomes

All patients had a complete excision of tumor. There were no major surgical complications, and all were discharged without any major morbidity.

The patients were followed up for an average period of 55.4 months (ranging 10–146 months). The three patients with malignant GCT completed a total of four courses of PEB chemotherapy. None of the patients had tumor recurrence. All the patients were alive and disease free during their last follow-up. [Table 1] summarizes the management and outcomes of these patients with giant mediastinal GCTs.

Table 1 Summary of management and outcome of patients with giant mediastinal germ cell tumors (n=12)

Discussion

The mediastinal lesions occurring in children are neurogenic tumors, mesenchymal tumors, lymphomas, thyroid lesions, GCTs, and various types of cysts in that order.[5] Primary mediastinal GCTs comprise only 6%–18% of pediatric mediastinal neoplasms.[1] [2] [3] Our incidence of 3.5% is lesser than the incidence of 5.4%–7.5%,[7] [13] [14] of mediastinal GCTs reported recently from other centers. Giant mediastinal GCTs are even rarer and pose a treatment challenge as they often compress and displace vital structures in the chest,[4] and pose significant anesthetic risk. Most cases of giant mediastinal GCTs have been reported in an older age group probably due to a comparatively larger chest cavity; the tumor may grow up to greater sizes before the symptoms become evident.[4] [15] This study highlights the successful management of 12 such pediatric cases.

Children presented during infancy (41.7%) and after 10 years of age (33.3%) showing a bimodal age distribution, which is similar to that reported previously.[6] Male preponderance was observed (M:F = 11:1) which is in sharp contrast to other extragonadal GCTs which show female preponderance.[16] [17] Most children (83%) were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis and presented with a recurrent chest infection, cough, and dyspnea. One child was diagnosed incidentally on radiologic imaging following chest trauma. Thus, pointing to the fact that prolonged respiratory symptoms in a child should raise the suspicion of a mediastinal tumor. These symptoms may be due to compression or rarely direct invasion.[7] Some children may also present with nonspecific symptoms such as weakness, loss of appetite, lethargy, chest pain, and superior vena cava syndrome.[5] [18]

According to the GCT management protocol at our institute, preoperative investigations included imaging and tumor markers (αFP and βHCG). Raised serum αFP levels indicate the presence of yolk sac in tumor mixed GCTs. Therefore, patients with raised αFP were managed as malignant GCTs. Tumor marker measurement is mandatory in assessing the response to chemotherapy, especially in malignant GCT. All three malignant GCT patients responded well to platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy showing a significant fall in αFP. However, no significant decrease in size was observed. This was probably due to large areas of mature elements in the mixed tumors. During surveillance, tumor markers should be supplementary to imaging studies and should not replace imaging. Studies show that patients may die of progressive disease despite normalization of tumor marker levels.[7]

An initial biopsy was not routinely done in our patients. However, a preoperative biopsy is warranted in patients with nonsecretory tumors with suspicion of malignancy on radiology. An initial biopsy yielded diagnosis of teratoma in two such cases but was inconclusive in one. It may also be important in the follow-up of patients with residual disease who undergo malignant transformation or develop non-germ cell malignancies.[19] [20]

CECT scan proved crucial in planning the type of surgical approach. The treatment of choice for all mediastinal GCTs is surgical removal.[5] [7] [17] The MAKEI trial in Germany concluded that the prognosis of mediastinal teratoma was excellent after complete or microscopically incomplete resection.[5] A complete resection though difficult, but was possible even in giant mediastinal GCTs. In our study, 11 of 12 (91.7%) of the tumors underwent complete resection despite their huge sizes in the first attempt. Similar results were observed in 4/5 giant mediastinal teratomas reported by Grabski et al.[7] The following factors contributed to the surgical success.

A flexible surgical approach (posterolateral thoracotomy or median sternotomy or combined thoracotomy and laparotomy) depending on the anatomic location of the tumor and the involvement of adjacent vital structures. In our series, it was observed that two anterior mediastinal and one tumor occupying the right hemithorax were comfortably removed via this approach. Other surgical approaches have also been described for a safe removal of large thoracic tumors. Christison-Lagay et al.[21] have reported 80% OS in pediatric mediastinal tumors managed using clamshell and trap door approaches. Trapdoor incision allows access to the great vessels of the mediastinum and neck; it preserves the sternal clavicular articulation and also by utilizing a fifth inter-costal space incision for the anterior thoracotomy, preserves innervation of sternal portion of pectoralis major.[21]

Most importantly, a team effort by the pediatric surgeons, cardiothoracic-vascular surgeons, pediatric oncologists, pediatric anesthetists, and pediatric radiologists was required to successfully manage these large tumors. However, in cases where the tumor is closely adherent to airway, great vessels, or vital nerves (phrenic and vagus) a partial tumor removal without causing damage is acceptable as was done in one case in this series.

Three-fourths of the mediastinal GCTs were mature teratomas. Prior studies also show that 45%–80% of mediastinal GCTs are benign.[2] [5] [7] [22] After complete tumor excision, a close clinical follow-up of these patients is essential.

The malignant GCTs were treated with a multimodal approach which included four courses of PEB chemotherapy and surgery.[23] Staging and risk categorization should be done to decide regarding the chemotherapy.[24] [25] PEB is recommended as the standard regime in pediatric patients.

Stage I–II mediastinal tumors fall in the intermediate risk and Stage III–IV fall in the high-risk categories.[2] In all these three patients, a complete surgical resection was possible, and the OS was 100%. Neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by delayed resection has previously been proved to be superior for malignant GCTs as compared to primary resection.[7] [13] [23] Routinely, no radiotherapy has been advocated for malignant GCT patients. Recurrent GCTs that are unresectable following salvage chemotherapy may be treated with radiotherapy.[24]

The OS was 100% akin to OS >80% reported in Japanese children ( < 18 years) with malignant mediastinal GCTs.[17] Billmire et al.[6] reported 4 years’ EFS and OS of 69% and 71%, respectively. They suggested that age >15 years was a prognostic factor for mortality.[6] Grabski et al. in their study of 19 cases reported an OS of 75%. They suggested that the strongest independent prognostic factors for malignant mediastinal GCTs included metastatic disease (lung or other solid organs) at diagnosis, complete surgical resection with negative margins and platinum-based chemotherapy.[7]

Association of mediastinal GCTs with Klinefelter disease has been noted in literature.[26] [27] [28] However, in the present study, none of our patients had Klinefelter Disease.

Conclusions

Pediatric mediastinal GCTs fare better than most adult mediastinal tumors. A complete surgical resection of even giant mediastinal tumors is achievable in children. Malignant mediastinal GCTs are best managed by neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, reassessment, and delayed resection. Minor surgical complications can be easily managed. An overall good survival is possible in a child with giant mediastinal GCT.

Ethics statement

A proper informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients or their parents for treatment. Institutional Ethics Committee approval for the retrospective study was taken.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1 Billmire DF. Germ cell, mesenchymal, and thymic tumors of the mediastinum. Semin Pediatr Surg 1999; 8: 85-91

- 2 Mullen B, Richardson JD. Primary anterior mediastinal tumors in children and adults. Ann Thorac Surg 1986; 42: 338-45

- 3 Schneider DT, Calaminus G, Koch S, Teske C, Schmidt P, Haas RJ. et al. Epidemiologic analysis of 1,442 children and adolescents registered in the German germ cell tumor protocols. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004; 42: 169-75

- 4 Fumino S, Sakai K, Higashi M, Aoi S, Furukawa T, Yamagishi M. et al. Advanced surgical strategy for giant mediastinal germ cell tumor in children. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2017; 27: 51-5

- 5 Schneider DT, Calaminus G, Reinhard H, Gutjahr P, Kremens B, Harms D. et al. Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors in children and adolescents: Results of the German cooperative protocols MAKEI 83/86, 89, and 96. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 832-9

- 6 Billmire D, Vinocur C, Rescorla F, Colombani P, Cushing B, Hawkins E. et al. Malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors: An intergroup study. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36: 18-24

- 7 Grabski DF, Pappo AS, Krasin MJ, Davidoff AM, Rao BN, Fernandez-Pineda I. et al. Long-term outcomes of pediatric and adolescent mediastinal germ cell tumors: A single pediatric oncology institutional experience. Pediatr Surg Int 2017; 33: 235-44

- 8 Liu Y, Wang Z, Peng ZM, Yu Y. Management of the primary malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors: Experience with 54 patients. Diagn Pathol 2014; 9: 33

- 9 Marina N, London WB, Frazier AL, Lauer S, Rescorla F, Cushing B. et al. Prognostic factors in children with extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors: A pediatric intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2544-8

- 10 Paradies G, Zullino F, Orofino A, Leggio S. Mediastinal teratomas in children. Case reports and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir 2013; 84: 395-403

- 11 Martino F, Avila LF, Encinas JL, Luis AL, Olivares P, Lassaletta L. et al. Teratomas of the neck and mediastinum in children. Pediatr Surg Int 2006; 22: 627-34

- 12 Göbel U, Calaminus G, Engert J, Kaatsch P, Gadner H, Bökkerink JP. et al. Teratomas in infancy and childhood. Med Pediatr Oncol 1998; 31: 8-15

- 13 De Pasquale MD, Crocoli A, Conte M, Indolfi P, D’Angelo P, Boldrini R. et al. Mediastinal germ cell tumors in pediatric patients: A report from the Italian association of pediatric hematology and oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016; 63: 808-12

- 14 Gun F, Erginel B, Unüvar A, Kebudi R, Salman T, Celik A. et al. Mediastinal masses in children: Experience with 120 cases. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012; 29: 141-7

- 15 Hayati F, Ali NM, Kesu Belani L, Azizan N, Zakaria AD, Rahman MR. et al. Giant mediastinal germ cell tumour: An enigma of surgical consideration. Case Rep Surg 2016; 2016: 7615029

- 16 Liu T, Al-Kzayer LFY, Xie X, Fan H, Sarsam SN, Nakazawa Y. et al. Mediastinal lesions across the age spectrum: A clinicopathological comparison between pediatric and adult patients. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 59845-53

- 17 Takeda S, Miyoshi S, Ohta M, Minami M, Masaoka A, Matsuda H. et al. Primary germ cell tumors in the mediastinum: A 50-year experience at a single Japanese institution. Cancer 2003; 97: 367-76

- 18 Lack EE, Weinstein HJ, Welch KJ. Mediastinal germ cell tumors in childhood. A clinical and pathological study of 21 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985; 89: 826-35

- 19 Biskup W, Calaminus G, Schneider DT, Leuschner I, Göbel U. Teratoma with malignant transformation: Experiences of the cooperative GPOH protocols MAKEI 83/86/89/96. Klin Padiatr 2006; 218: 303-8

- 20 Ulbright TM, Loehrer PJ, Roth LM, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Clark SA. et al. The development of non-germ cell malignancies within germ cell tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Cancer 1984; 54: 1824-33

- 21 Christison-Lagay ER, Darcy DG, Stanelle EJ, Dasilva S, Avila E, La Quaglia MP. et al. “Trap-door” and “clamshell” surgical approaches for the management of pediatric tumors of the cervicothoracic junction and mediastinum. J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49: 172-6

- 22 Yalçın B, Demir HA, Tanyel FC, Akçören Z, Varan A, Akyüz C. et al. Mediastinal germ cell tumors in childhood. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012; 29: 633-42

- 23 Agarwala S, Mitra A, Bansal D, Kapoor G, Vora T, Prasad M. et al. Management of pediatric malignant germ cell tumors: ICMR consensus document. Indian J Pediatr 2017; 84: 465-72

- 24 Cushing B, Giller R, Cullen JW, Marina NM, Lauer SJ, Olson TA. et al. Randomized comparison of combination chemotherapy with etoposide, bleomycin, and either high-dose or standard-dose cisplatin in children and adolescents with high-risk malignant germ cell tumors: A pediatric intergroup study – Pediatric oncology group 9049 and children’s cancer group 8882. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 2691-700

- 25 Jain V, Agarwala S, Bakshi S, Srinivas M, Bajpai M, Bhatnagar V. et al. Malignant germ cell tumors in children: Management and outcomes from AIIMS-MGCT 94 trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer Supplement 2009(0.073):732-3

- 26 Hartmann JT, Nichols CR, Droz JP, Horwich A, Gerl A, Fossa SD. et al. Hematologic disorders associated with primary mediastinal non seminoma to us germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 54-61

- 27 Nichols CR, Hoffman R, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Wheeler LA, Garnick MB. et al. Hematologic malignancies associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumors. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102: 603-9

- 28 Nichols CR, Roth BJ, Heerema N, Griep J, Tricot G. Hematologic neoplasia associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumors. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 1425-9

Address for correspondence

Dr. Sandeep AgarwalaDepartment of Pediatric Surgery, All India Institute of Medical SciencesR. No 4007, New DelhiIndiaEmail: sandpagr@hotmail.comPublication History

Received: 10 April 2018

Accepted: 18 October 2018

Article published online:

03 June 2021© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Fig. 1 Management protocol followed for mediastinal germ cell tumors. GCT – Germ cell tumors; αFP – Alpha-fetoprotein; PEB – Cisplatin, Etoposide, and Bleomycin

| Fig. 2 Computed tomography scan coronal (a) and axial sections (b and c) showing a Giant malignant germ cell tumors pushing the right dome of diaphragm down till the pelvis

| Fig. 3 Chest X-ray anterior-posterior, lateral view (a and b) showing anterior mediastinal mass. (c) Computed tomography scan of the same patient with areas of calcification and fat in the tumor. (d and e) Right posterolateral thoracotomy and excision of the mass

References

- 1 Billmire DF. Germ cell, mesenchymal, and thymic tumors of the mediastinum. Semin Pediatr Surg 1999; 8: 85-91

- 2 Mullen B, Richardson JD. Primary anterior mediastinal tumors in children and adults. Ann Thorac Surg 1986; 42: 338-45

- 3 Schneider DT, Calaminus G, Koch S, Teske C, Schmidt P, Haas RJ. et al. Epidemiologic analysis of 1,442 children and adolescents registered in the German germ cell tumor protocols. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004; 42: 169-75

- 4 Fumino S, Sakai K, Higashi M, Aoi S, Furukawa T, Yamagishi M. et al. Advanced surgical strategy for giant mediastinal germ cell tumor in children. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2017; 27: 51-5

- 5 Schneider DT, Calaminus G, Reinhard H, Gutjahr P, Kremens B, Harms D. et al. Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors in children and adolescents: Results of the German cooperative protocols MAKEI 83/86, 89, and 96. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 832-9

- 6 Billmire D, Vinocur C, Rescorla F, Colombani P, Cushing B, Hawkins E. et al. Malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors: An intergroup study. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36: 18-24

- 7 Grabski DF, Pappo AS, Krasin MJ, Davidoff AM, Rao BN, Fernandez-Pineda I. et al. Long-term outcomes of pediatric and adolescent mediastinal germ cell tumors: A single pediatric oncology institutional experience. Pediatr Surg Int 2017; 33: 235-44

- 8 Liu Y, Wang Z, Peng ZM, Yu Y. Management of the primary malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors: Experience with 54 patients. Diagn Pathol 2014; 9: 33

- 9 Marina N, London WB, Frazier AL, Lauer S, Rescorla F, Cushing B. et al. Prognostic factors in children with extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors: A pediatric intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2544-8

- 10 Paradies G, Zullino F, Orofino A, Leggio S. Mediastinal teratomas in children. Case reports and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir 2013; 84: 395-403

- 11 Martino F, Avila LF, Encinas JL, Luis AL, Olivares P, Lassaletta L. et al. Teratomas of the neck and mediastinum in children. Pediatr Surg Int 2006; 22: 627-34

- 12 Göbel U, Calaminus G, Engert J, Kaatsch P, Gadner H, Bökkerink JP. et al. Teratomas in infancy and childhood. Med Pediatr Oncol 1998; 31: 8-15

- 13 De Pasquale MD, Crocoli A, Conte M, Indolfi P, D’Angelo P, Boldrini R. et al. Mediastinal germ cell tumors in pediatric patients: A report from the Italian association of pediatric hematology and oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016; 63: 808-12

- 14 Gun F, Erginel B, Unüvar A, Kebudi R, Salman T, Celik A. et al. Mediastinal masses in children: Experience with 120 cases. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012; 29: 141-7

- 15 Hayati F, Ali NM, Kesu Belani L, Azizan N, Zakaria AD, Rahman MR. et al. Giant mediastinal germ cell tumour: An enigma of surgical consideration. Case Rep Surg 2016; 2016: 7615029

- 16 Liu T, Al-Kzayer LFY, Xie X, Fan H, Sarsam SN, Nakazawa Y. et al. Mediastinal lesions across the age spectrum: A clinicopathological comparison between pediatric and adult patients. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 59845-53

- 17 Takeda S, Miyoshi S, Ohta M, Minami M, Masaoka A, Matsuda H. et al. Primary germ cell tumors in the mediastinum: A 50-year experience at a single Japanese institution. Cancer 2003; 97: 367-76

- 18 Lack EE, Weinstein HJ, Welch KJ. Mediastinal germ cell tumors in childhood. A clinical and pathological study of 21 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985; 89: 826-35

- 19 Biskup W, Calaminus G, Schneider DT, Leuschner I, Göbel U. Teratoma with malignant transformation: Experiences of the cooperative GPOH protocols MAKEI 83/86/89/96. Klin Padiatr 2006; 218: 303-8

- 20 Ulbright TM, Loehrer PJ, Roth LM, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Clark SA. et al. The development of non-germ cell malignancies within germ cell tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Cancer 1984; 54: 1824-33

- 21 Christison-Lagay ER, Darcy DG, Stanelle EJ, Dasilva S, Avila E, La Quaglia MP. et al. “Trap-door” and “clamshell” surgical approaches for the management of pediatric tumors of the cervicothoracic junction and mediastinum. J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49: 172-6

- 22 Yalçın B, Demir HA, Tanyel FC, Akçören Z, Varan A, Akyüz C. et al. Mediastinal germ cell tumors in childhood. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012; 29: 633-42

- 23 Agarwala S, Mitra A, Bansal D, Kapoor G, Vora T, Prasad M. et al. Management of pediatric malignant germ cell tumors: ICMR consensus document. Indian J Pediatr 2017; 84: 465-72

- 24 Cushing B, Giller R, Cullen JW, Marina NM, Lauer SJ, Olson TA. et al. Randomized comparison of combination chemotherapy with etoposide, bleomycin, and either high-dose or standard-dose cisplatin in children and adolescents with high-risk malignant germ cell tumors: A pediatric intergroup study – Pediatric oncology group 9049 and children’s cancer group 8882. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 2691-700

- 25 Jain V, Agarwala S, Bakshi S, Srinivas M, Bajpai M, Bhatnagar V. et al. Malignant germ cell tumors in children: Management and outcomes from AIIMS-MGCT 94 trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer Supplement 2009(0.073):732-3

- 26 Hartmann JT, Nichols CR, Droz JP, Horwich A, Gerl A, Fossa SD. et al. Hematologic disorders associated with primary mediastinal non seminoma to us germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 54-61

- 27 Nichols CR, Hoffman R, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Wheeler LA, Garnick MB. et al. Hematologic malignancies associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumors. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102: 603-9

- 28 Nichols CR, Roth BJ, Heerema N, Griep J, Tricot G. Hematologic neoplasia associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumors. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 1425-9

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share