Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Clinical Outcomes among Men with Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ? Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2018; 39(02): 127-141

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_61_17

Abstract

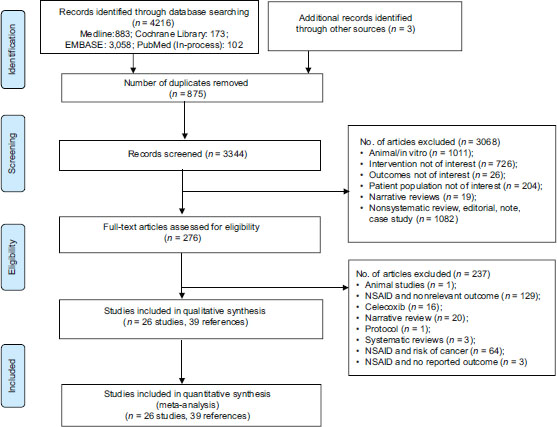

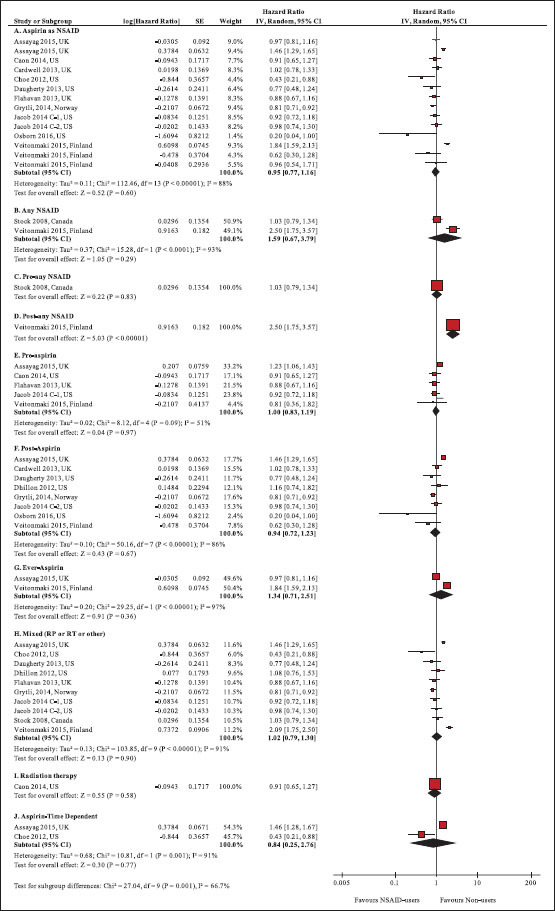

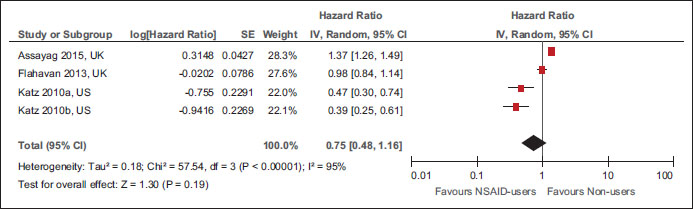

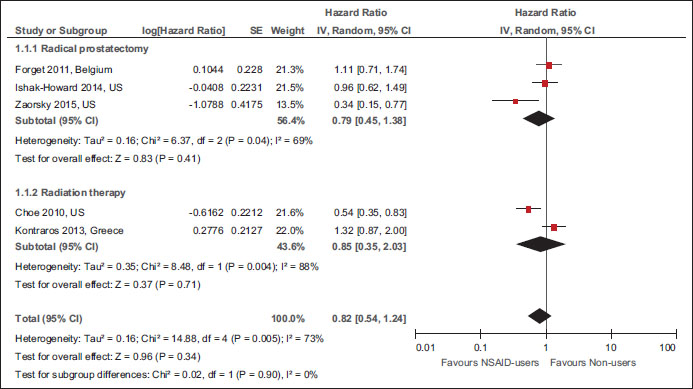

Background:?Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have shown properties of inhibiting the progression of prostate cancer (PCa) in preclinical studies. However, epidemiological studies yield mixed results on the effectiveness of NSAIDs in PCa.?Objective:?The objective of this study was to determine the effect of NSAID use on clinical outcomes in PCa using systematic review and meta-analysis.?Methods:?Original articles published until the 1st week of October, 2016, were searched in electronic databases (Medline-Ovid, PubMed, Scopus, The Cochrane Library, and Web of Science) for studies on NSAID use in PCa. The main clinical outcomes for the review were: PCa-specific (PCM) and all-cause mortality (ACM), biochemical recurrence (BCR), and metastases. Meta-analysis was performed to calculate the pooled hazard ratio (pHR) and their 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Heterogeneity between the studies was examined using I2?statistics. Appropriate subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the reasons for heterogeneity.?Results:?Out of 4216 retrieved citations, 24 observational studies and two randomized controlled studies with a total of 89,436 men with PCa met the inclusion criteria. Overall, any NSAID use was not associated with PCM, ACM, and BCR, with significant heterogeneity. Neither precancer treatment aspirin use (pHR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.83, 1.19,?P?= 0.97, 5 studies, I2: 51%) nor postcancer treatment aspirin use (pHR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.72, 1.23,?P?= 0.67, 8 studies, I2: 86%) was associated with PCM. Similar findings, that is, no significant association was observed for NSAID use and ACM or BCR overall, and in subgroup by types of NSAID use, and NSAID use following radiation or surgery.?Conclusion:?Although NSAID use was not associated with ACM, PCM, or BCR among men with PCa, significant heterogeneity remained in the included studies even after subgroup analyses.

Publication History

Article published online:

23 June 2021

? 2018. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background:?Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have shown properties of inhibiting the progression of prostate cancer (PCa) in preclinical studies. However, epidemiological studies yield mixed results on the effectiveness of NSAIDs in PCa.?Objective:?The objective of this study was to determine the effect of NSAID use on clinical outcomes in PCa using systematic review and meta-analysis.?Methods:?Original articles published until the 1st week of October, 2016, were searched in electronic databases (Medline-Ovid, PubMed, Scopus, The Cochrane Library, and Web of Science) for studies on NSAID use in PCa. The main clinical outcomes for the review were: PCa-specific (PCM) and all-cause mortality (ACM), biochemical recurrence (BCR), and metastases. Meta-analysis was performed to calculate the pooled hazard ratio (pHR) and their 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Heterogeneity between the studies was examined using I2?statistics. Appropriate subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the reasons for heterogeneity.?Results:?Out of 4216 retrieved citations, 24 observational studies and two randomized controlled studies with a total of 89,436 men with PCa met the inclusion criteria. Overall, any NSAID use was not associated with PCM, ACM, and BCR, with significant heterogeneity. Neither precancer treatment aspirin use (pHR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.83, 1.19,?P?= 0.97, 5 studies, I2: 51%) nor postcancer treatment aspirin use (pHR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.72, 1.23,?P?= 0.67, 8 studies, I2: 86%) was associated with PCM. Similar findings, that is, no significant association was observed for NSAID use and ACM or BCR overall, and in subgroup by types of NSAID use, and NSAID use following radiation or surgery.?Conclusion:?Although NSAID use was not associated with ACM, PCM, or BCR among men with PCa, significant heterogeneity remained in the included studies even after subgroup analyses.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common nonskin cancer with an estimated 508,345,355 survivors and 1,392,727 incident cases by 2020 as per the World Health Organization's report of 184 countries. PCa accounts for 15% of incident cancer cases diagnosed in men as of 2012 and is the fifth leading cause of death due to cancer in men.[1] Along the global disease burden, the worldwide cost of cancer medications is expected to increase by 11.5% from $107 billion in 2015 to 150 billion by 2020, attributed mainly to newly approved cancer chemotherapy.[2] With advance in the health-care management and focus on the value-based incentive payment models, there are needs to find potentially effective and affordable care among men with PCa.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been the first line of treatment to relieve pain and fever ? two common indicators of majority of diseases. With aspirin being the first NSAID, NSAIDs have seven chemical classes: salicylates, fenamates, para-aminophenol, acetic acid, enolic acid and propionic acid derivatives, and diaryl heterocyclic.[3] Biologically, NSAIDs inhibit development prostanoids by blocking the activity of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes. Blockage of COX enzyme activity leads to a cascade of beneficial reactions inhibiting inflammatory response in cancer. For example, preclinical studies have found that NSAIDs inhibit platelet activation which in turn inhibits the development of aggressive cancers and metastases. Such studies have demonstrated that activated platelet could lead to carcinogenesis via releasing angiogenic factors, forming platelet?tumor cell aggregates, and evading immune surveillance in the blood.[4],[5] In addition, NSAIDs could also play a role by inhibiting cancer-related inflammation such as the infiltration of white blood cells; tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs); cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-?; chemokines such as (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and CXCL8; acceleration of cell cycle progression and cell proliferation; evasion from apoptosis; and stimulation of tumor angiogenesis.[6],[7] Therefore, the NSAID may serve as a novel therapeutic option to manage PCa.

Epidemiological studies on NSAIDs yielded mixed results on the association between NSAIDs and clinical outcomes among men with PCa. Previously Liu?et al. conducted a systematic review of eight observational studies and found beneficial association of NSAID and PCa-specific mortality (PCM) for certain subgroups using published literature until 2013.[8] However, there still remains the need for future research to explore significant heterogeneity in the pooled study estimates with limited subgroup analyses. In addition, Liu?et al. did neither examine association between the NSAID use and biochemical recurrence (BCR), metastases, or all-cause mortality (ACM) among men with PCa, nor examine the effect of primary cancer treatment in men with PCa. With available recent publications, there is a need to re-evaluate the impact of NSAIDs and PCa-related outcomes. There have been publications of many studies since the date of search of previous two systematic reviews. Therefore, we carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the effect of NSAID on the clinical outcomes such as PCM, ACM, BCR, and metastases among men with PCa.

Methods

We followed the standard guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [9] and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology statement [10] to conduct and report the current systematic review and meta-analysis.

Criteria for study selection

Our systematic review included both prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs), as well as prospective and retrospective nonrandomized a.k.a observational studies examining the effects of NSAIDs among men with PCa. However, we excluded experimental studies a. k. a cell lines,in vitro?and animal studies, and studies with shorter duration (?6 months) of follow-up. The main outcomes of interest for our review were PCM, ACM, BCR, and development of metastases.

Data sources and searches

We searched electronic databases (Medline [Ovid], Scopus, and the Cochrane library) to identify published articles on topic of our interest from the inception of each database to the 2nd week of March 2016. In addition, we also searched the Web of Science (WOS) to identify gray literature related to conference abstracts from the inception of WOS to the 3rd week of July 2016. We searched these databases using keywords such as ?Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,? ?Aspirin,? ?prostate neoplasm,? and ?prostate cancer.? We reported the details of search strategy for each database in Appendix 1 with keywords and number of retrieved citations per string. Further, we created a weekly alter for new citations' electronic databases. As of now, we included articles available in weekly search until October 10, 2016. Furthermore, we also scanned through the reference lists of identified studies for additional relevant studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (NR and DT) independently assessed the retrieved articles and gray literature for inclusion of articles in the review. We also checked the agreement for inclusion and exclusion of studies between two authors using the kappa statistic. In case of discrepancies about the inclusion or exclusion between two authors, a third author (ADR) resolved the issues with consensus. Three authors (ADR, NR, and DT) independently extracted information from the included studies using a data extraction template. The data extraction template has information on study design, country of participants, year of publication, sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria of individual studies, PCa stage and severity-related variables, duration of NSAID use, and type and other baseline characteristics. In addition, we also extracted reported outcomes from each study on BCR, metastases, ACM, and PCM with details on statistical parameters such as number of events, median time to outcomes, unadjusted rates of outcomes, and unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs).

We utilized the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) tool to examine the risk of bias in included observational studies. The NOS allots up to nine points for the least risk of bias in three domains: (1) selection of study groups (four points); (2) comparability of groups (two points); and (3) ascertainment of exposure and outcomes (three points) for cohort studies. The risk of bias or poor quality was considered as ?high? with one or four score total scores, ?fair? with a total score of 4?6, and ?good? with a total score 7 or more.[11] In addition, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool to evaluate the risk of bias for performance, selection, reporting, and detecting bias domain for RCTs.[12]

Data synthesis and analysis

We computed a pooled hazard ratio (pHR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for all clinical outcomes reported in the included studies using random-effects models. We used the Cochrane Chi-square (Cochran Q) statistic and the I2?test to analyze heterogeneity across included studies.[13] In the presence of heterogeneity of pooled estimates, we performed subgroup analyses by study design, countries of studies, cancer stage, primary cancer treatment, types of NSAIDs, timing of NSAID exposures, and potential adjusted confounders. We also determined the presence of publication bias for observational studies using Egger's method (Kendall's Tau)[14] and using a contour-enhanced funnel plot to determine other causes of publication bias by examining the symmetry of the plot.[15] All the analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Results

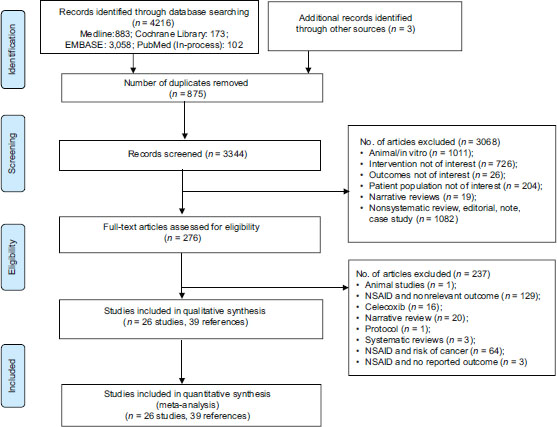

We identified 4219 citations through electronic databases and other resources. Out of the 4219 citations, we removed 875 duplicates with 3344 citations eligible for first-level screening. We excluded 3068 citations in the first pass based on title and abstract and 237 citations in the second level screening based on full-text information. We excluded the following studies: animal models,in vitro studies, reviews, RCTs on interventions other than NSAIDs, RCTs or observational studies on NSAID use in noncancer population, and studies assessing the risk of PCa with the use of NSAIDs. Finally, a total of 26 studies (39 references) met inclusion criteria for our review. [Figure 1] depicts the study selection process as per the PRISMA framework from the retrieved citations.

|?Figure.1Systematic review and meta-analyses flow chart for study selection for the systematic review on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and clinical outcomes in men with prostate cancer. RCT: Randomized Controlled Trials

Characteristics of included studies

[Table 1] describes the general characteristics of included studies published between 2001 and 2016. We identified 24 observational studies and two randomized controlled studies with a total pooled cohort of 89,436 men with PCa. The included studies had a total of 69,247 men from 20 retrospective cohort studies,[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[40],[41] 13,855 men from two prospective cohort studies,[34],[35] 1619 men from one case cohort study [36] and 4715 men from one nested case?control study,[37] and 300 men from two prospective randomized controlled studies.[38],[39] Seventeen studies were carried out in the United States,[16],[17],[18],[20],[21],[26],[27],[28],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[38],[39],[40],[41] three in the United Kingdom (UK),[22],[29],[37] two in Canada,[24],[36] one each in Belgium,[19] Greece,[30] Finland,[41] and Norway.[25] The sample size of the study cohort ranged between 74[27] and 11,779.[29] With respect to types of NSAID use, 23 of the included studies reported aspirin as the NSAID, one of the each studies reported Exisulind and Ketorolac, and two studies did not specify the type of NSAIDs. The proportion of men with NSAID use ranged from 9.7%[30] to 66%.[18] All the included studies had at least 1 year of median follow-up period with a maximum median duration of 9.25 years in a study.[32]

|

Study name |

Study design |

Time frame |

Study sample |

Types of NSAID |

Number of NSAID users |

Percentage of NSAID users |

Follow-up (median, IQR), in years |

Stage of cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

aCardwell et al. had a total of 453 cases and 1619 men in the subcohort, bStock et al. had 1184 cases and 3531 controls of which 617 cases and 1365 controls used any NSAID, cOther NSAID use includes the use of diclofenac, naproxen, indomethacin, and ibuprofen. IQR -?Interquartile range; NCCS -?Nested case-control study; NSAIDs -?Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCa -?Prostate cancer; PCS -?Prospective cohort study; RCS -?Retrospective cohort study; RCT -?Randomized controlled trial; ASA -?Aspirin |

||||||||

|

Radical prostatectomy |

||||||||

|

Goluboff, 2001, US |

RCT |

2000-2001 |

94 |

Exisulind |

47 |

50 |

1 |

Any PCa |

|

Forget, 2011, Belgium |

RCS |

1993-2006 |

1111 |

Ketorolac |

278 |

25 |

3.16 (1.33-5.75) |

Any PCa |

|

Mondul, 2011, US |

RCS |

1993-2006 |

2399 |

ASA |

1584 |

66 |

7 |

Localized PCa |

|

Kontraros, 2013, Greece |

RCS |

1999-2010 |

588 |

ASA |

74 |

13 |

p: 3.4 (SD: 2.6) |

Any PCa |

|

Ishak-Howard, 2014, US |

RCS |

1999-2009 |

539 |

ASA |

270 |

50 |

p: 7.9 (SD: 4.7) |

Any PCa |

|

Zaorsky, 2015, US |

RCS |

1991-2008 |

189 |

ASA |

60 |

32 |

4.17 (0.28, 17.8) |

Localized PCa |

|

Radiation therapy |

||||||||

|

Zaorsky, 2011, US |

RCS |

1989-2006 |

2051 |

ASA |

743 |

36 |

6.3 (1.5-19.9) |

Localized PCa |

|

Caon, 2014, Canada |

RCS |

2000-2007 |

3851 |

ASA |

917 |

24 |

8.0 |

Localized PCa |

|

Jacobs, 2014b, US |

RCS |

2005-2008 |

74 |

ASA |

41 |

55 |

4.63 |

Advanced PCa |

|

Choe, 2010, US |

RCS |

1988-2005 |

662 |

ASA |

196 |

30 |

4.08 |

Any PCa |

|

Osborn, 2016, US |

RCS |

2003-2010 |

469 |

ASA |

147 |

31 |

5.08 (2.42-6.83) |

Any PCa |

|

Active surveillance |

||||||||

|

Agarwal, 2015, US |

RCS |

1994-2000 |

102 |

NSAIDs |

51 |

50 |

9.25 (6.1-12.2) |

Localized PCa |

|

Any prostate cancer treatment |

||||||||

|

Ratansinghe, 2004, US |

PCS |

1971-1992 |

9,869 |

ASA |

3934 |

40 |

Any PCa |

|

|

D?Amico, 2008, US |

RCT |

1995-2001 |

206 |

ASA |

86 |

42 |

8.2 (7.0-9.5) |

Any PCa |

|

Choe, 2012, US |

RCS |

- |

5955 |

ASA |

1817 |

31 |

5.83 |

Any PCa |

|

Dhillon, 2012, US |

PCS |

1990-2005 |

3986 |

ASA |

1586 |

40 |

p: 8.4 |

Any PCa |

|

Cardwell, 2013a, UK |

NCCS |

1998-2006 |

4715 |

ASA |

1982 |

42 |

p: 6.0 |

Any PCa |

|

Daugherty, 2013, US |

RCS |

1993-2009 |

3857 |

ASA |

- |

- |

5 |

Any PCa |

|

Flahavan, 2013, UK |

RCS |

2001-2006 |

2936 |

ASA |

1131 |

39 |

5.5 |

Any PCa |

|

Grytli, 2014, Norway |

RCS |

2004-2009 |

3561 |

ASA |

1149 |

32 |

3.25 |

Any PCa |

|

Stock, 2008b, Canada |

Case-Cohort |

1990-1999 |

1619 |

ASA + others |

419 |

26 |

- |

Any PCa |

|

NSAIDs |

||||||||

|

Veitonmaki, 2015, |

RCS |

1996-2012 |

6537 |

ASA + others |

NSAID: |

NSAID: |

7.5 |

Any PCa |

|

Finland |

NSAIDs |

5,591; |

86%; ASA: |

|||||

|

ASA: 637 |

10 |

|||||||

|

Katz, 2010, US |

RCS |

1990-2003 |

7042 |

NSAIDs |

1830 |

26 |

4(0-16) |

Any PCa |

|

Jacob, 2014C-1, US |

RCS |

1992-2010 |

8427 |

ASA |

4827 |

57 |

p: 9.3 |

Localized PCa |

|

Jacobs, 2014-C2, US |

RCS |

1992-2010 |

7118 |

ASA |

4151 |

58 |

p: 8.4 |

Localized PCa |

|

Assayag, 2015, UK |

RCS |

1996-2012 |

11,779 |

ASA |

4147 |

35 |

p: 5.4 (SD: 2.9) |

Localized PCa |

|

Study name |

Study groups |

Age (years) |

Race/ ethnicity (%) |

Comorbidities (%) |

BMI (kg/m2) |

Smoking (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

? - mean; M - median; AA -?African-American; ASA -?Aspirin; BMI -?Body mass index; CCI -?Charlson Comorbidity Score; COPD -?Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD -?Cardiovascular disease; DM -?Diabetes mellitus; HF -?Heart failure; HTN -?Hypertension; LT -?Less than; MI -?Myocardial infarction; NSAID -?Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OD -?Once daily; UK -?United kingdom; US -?United states; W -?Whites; ACS -?Adult Comorbidity Score-27; C/P -?Current smoker or past smoker |

||||||

|

Radical prostatectomy |

||||||

|

Mondul, 2011, US |

Overall |

|?Figure.1Systematic review and meta-analyses flow chart for study selection for the systematic review on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and clinical outcomes in men with prostate cancer. RCT: Randomized Controlled Trials

|?Figure.2Forest plot of comparison: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users versus nonusers for prostate cancer-specific mortality

|?Figure.3Forest plot of comparison: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users versus nonusers for all-cause mortality

|?Figure.4Forest plot of comparison: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users versus nonusers for biochemical recurrence References

| ||||

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share