Prospective Genomic Profiling Study in Sarcoma Patients

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025; 46(04): 377-383

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0045-1805022

Abstract

Introduction Sarcoma is a heterogenous group of malignancy with diverse pathology and clinical behavior. Survival rates differ among histological subtypes, but overall prognosis remains poor due to the scarcity of effective systemic therapies. An insight into the genomic characteristics of different sarcoma histological subtypes enhances our understanding of the disease and highlights potential targeted therapies.

Objective We aim to enhance our understanding on the genomic profile of sarcomas and identify actionable genetic variants with the associated targeted therapies.

Materials and Methods A prospective tumor genomic profiling study was conducted via next-generation sequencing, involving 30 patients with a diagnosis of soft tissue or bone sarcoma at the University of Malaya Medical Centre. We evaluated the frequency and types of genomic aberrations and identified genomic variants with a therapeutic target.

Results A total of 70 genetic mutations were identified. The most frequently involved genes were TP53 (30.0%), followed by RB1 (20.0%), PIK3CA (10.0%), KIT (10.0%), PDGFR-α (10.0%), CKS1B (10.0%), KDR (10.0%), and MCL1 (10.0%). Genomic alteration involving the ALK gene was the only actionable variant identified. The DCTN1–ALK fusion was found to be targetable using entrectinib.

Conclusion Although the number of actionable variants identified was limited, such data are crucial for the selection of patients into clinical trials on novel therapies in the future and for establishing prognostic biomarkers.

Keywords

sarcoma - genomics - mutation - entrectinib

Data Availability Statement

The data (i.e., FoundationOne Heme test results) used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors' Contributions

G.F.H. designed, conducted, and supervised the study. E.V.C. conducted the literature search and drafted and edited the manuscript. W.Y.C. performed data collection and assisted the patients in the enrollment process. K.S.M. reviewed and prepared the patients' tumor samples to ensure quality control standards were met for genomic profiling. R.A.M. was involved in patient recruitment. M.S. was involved in patient recruitment.

All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Each named author has substantially contributed to conducting this study and the writing of this article. This manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all the coauthors.

Patient's Consent

Written, informed consent was taken from each participant after explanation of the aims, methods, and anticipated benefits of the study.

Publication History

03 March 2025

© 2025. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Adult Soft Tissue Sarcoma: A Prospective Observational Real-World DataShivashankara Mathighatta Shivarudraiah, Indian J Radiol Imaging, 2021

- Toward a Better Understanding of the Use of Targeted Therapies in Pediatric Sarcoma PatientsLars M. Wagner, Journal of Pediatric Biochemistry, 2016

- Analysis of Dedifferentiated Liposarcomas Emphasizing the Diagnostic DilemmasBhagat Singh Lali, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2020

- Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy versus fine-needle aspiration for genomic profiling and DNA yield in pancreatic cancer: a randomiz...Pujan Kandel, Endoscopy

- Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy versus fine-needle aspiration for genomic profiling and DNA yield in pancreatic cancer: a randomiz...Pujan Kandel, Zentralblatt für Chirurgie - Zeitschrift für Allgemeine, Viszeral-, Thorax- und Gefäßchirurgie

- Monocyte-lineage tumor infiltration predicts immunoradiotherapy response in advanced pretreated soft-tissue sarcoma: phase 2 trial results<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> Antonin Lévy, et al., Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2025 - Predicting the next move: tracking the complexity of lung cancer evolution and metastasisCarina Lorenz, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023

- Research Progress on Postoperative Minimal/Molecular Residual Disease Detection in Lung Cancer<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> Manqi Wu, Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine, 2022 - Risk of thoracic soft tissue sarcoma after breast cancer radiotherapy: a population-based cohort study in Osaka, JapanToshiki Ikawa, Journal of Radiation Research

- Bypassing reproductive barriers by chemical epimutagenesisSylvain Bischof, The Plant Cell, 2022

Abstract

Introduction Sarcoma is a heterogenous group of malignancy with diverse pathology and clinical behavior. Survival rates differ among histological subtypes, but overall prognosis remains poor due to the scarcity of effective systemic therapies. An insight into the genomic characteristics of different sarcoma histological subtypes enhances our understanding of the disease and highlights potential targeted therapies.

Objective We aim to enhance our understanding on the genomic profile of sarcomas and identify actionable genetic variants with the associated targeted therapies.

Materials and Methods A prospective tumor genomic profiling study was conducted via next-generation sequencing, involving 30 patients with a diagnosis of soft tissue or bone sarcoma at the University of Malaya Medical Centre. We evaluated the frequency and types of genomic aberrations and identified genomic variants with a therapeutic target.

Results A total of 70 genetic mutations were identified. The most frequently involved genes were TP53 (30.0%), followed by RB1 (20.0%), PIK3CA (10.0%), KIT (10.0%), PDGFR-α (10.0%), CKS1B (10.0%), KDR (10.0%), and MCL1 (10.0%). Genomic alteration involving the ALK gene was the only actionable variant identified. The DCTN1–ALK fusion was found to be targetable using entrectinib.

Conclusion Although the number of actionable variants identified was limited, such data are crucial for the selection of patients into clinical trials on novel therapies in the future and for establishing prognostic biomarkers.

Keywords

sarcoma - genomics - mutation - entrectinib

Introduction

Sarcoma is a rare group of mesenchymal neoplasm, comprising approximately 1% of all adult malignancies.[1] It comprises more than 70 histological subtypes and is especially challenging to study and treat given its diverse pathologies and clinical trajectories.[2] Survival rates vary across histological subtypes, but overall, prognosis is poor due to the limited effective systemic therapies. Five-year survival rates for metastatic soft tissue and bone sarcoma range between 15 and 24%.[3] [4]

An insight into the genomic profile of different sarcoma histological subtypes facilitates our understanding of the disease and the potential targeted therapies that may improve prognosis. A high unmet need exists to explore options beyond conventional chemotherapeutic approach in the treatment of inoperable or metastatic sarcoma across different histological subtypes.

In this study, we sought to utilize next-generation sequencing to ascertain the types and prevalence of genetic mutations across various histological subtypes of sarcoma. Our primary goal was to present an in-depth evaluation of the genomic profiles found in sarcoma that could be used to identify therapeutically actionable mutations and their associated targeted therapies. Our hypothesis is that there is a small number of actionable mutations with approved targeted therapies.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This single-center prospective study was conducted from August 2020 to July 2021 at the University of Malaya Medical Centre, a tertiary referral hospital with oncology services in Malaysia. Data cutoff was on July 31, 2021. All participants provided written informed consent prior to any study procedures.

Patients

Patients with a diagnosis of sarcoma confirmed via histopathological examination and tumor material suitable for genomic assay were deemed eligible for this study. Written informed consent prior to participation was a requirement. For patients under the age of 18 years, a legally authorized representative was required to consent on the patient's behalf. Patients were excluded from the study if they were pregnant or unwilling to provide written informed consent.

The study did not require the patient to attend additional visits to the clinic other than the routine visits planned by their treating doctors during the study inclusion period.

Sampling Protocol

Patient data including demographics and clinical information were extracted from electronic medical records. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue was obtained from each patient. Tumor samples from these patients were either FFPE blocks or 10 to 15 unstained slides with one original hematoxylin and eosin slide. The submission criteria for the submitted tissue samples included at least 25 mm2 of surface area, and a thickness of 4 to 5 μm. To maintain sensitivity for the detection of genomic alteration, it was a requirement for viable tumor cells to comprise at least 20% of the specimen.

Tumor samples were sent for comprehensive genomic profiling (FoundationOne Heme test) at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certified laboratory (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States). The FoundationOne Heme test is designed to detect genomic changes across numerous cancer-related genes in sarcomas. DNA sequencing was utilized to interrogate 406 genes and introns of 31 genes, and RNA sequencing for additional 265 genes. Microsatellite stability was evaluated by analyzing insertion and deletion characteristics at 114 homopolymer repeat loci within or near the targeted gene regions. Tumor mutational burden was established by measuring the number of somatic mutations in the sequenced genes.

The primary outcomes in this study are the prevalence and types of genomic alterations in sarcoma patients. The secondary outcomes are the demographics and the histologic subtypes of sarcoma in our study population.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses included counts and percentages for categorical variables and the median, minimum, and maximum for continuous variables.

Ethical Approval

Study approval was granted by the Medical Research Ethics Committee at the University of Malaya Medical Centre on August 11, 2020 (ethics approval number: 2020723- 8909). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and the International Council on Harmonization guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Thirty-five patients with histopathological confirmation of sarcoma diagnosis consented to be enrolled in the study. Five patients were excluded as their tumor samples did not meet the quality control standards of the laboratory or our histopathologist (2 insufficient tissue samples, 1 insufficient tissue cellularity, 1 extensive decalcification, and 1 with multiple DNA signatures). Thirty patients underwent tumor genomic profiling.

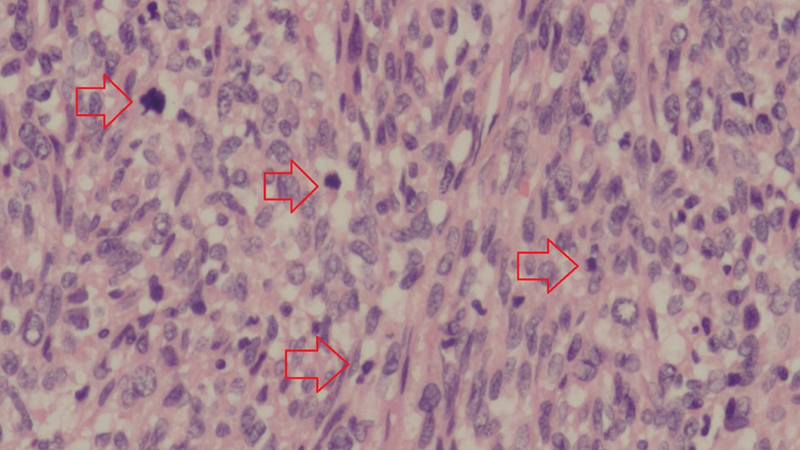

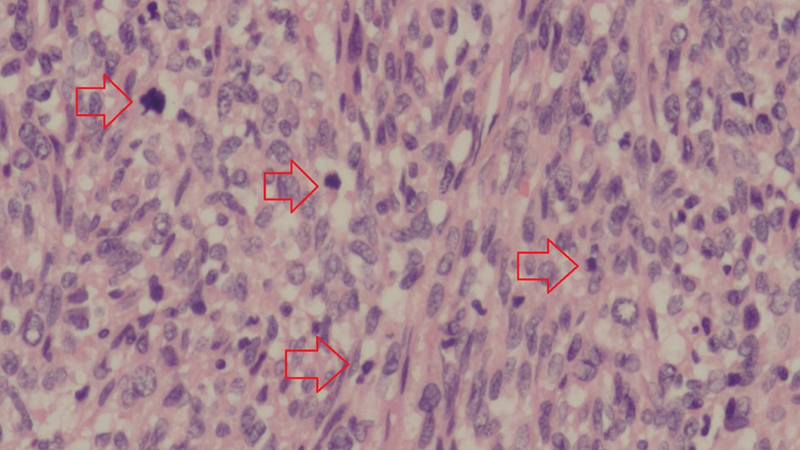

The baseline characteristics of the 30 sarcoma patients who underwent tumor genetic profiling are summarized in [Table 1]. The median age of the patients was 42.5 years, ranging from 21 to 77 years. The majority of the patients were females (66.7%) and Chinese (83.3%). Soft tissue sarcoma was the most common type of sarcoma observed in patients enrolled in this study (n = 26; 86.7%). Seventeen sarcoma subtypes were identified in total. The most common sarcoma subtype was leiomyosarcoma (n = 5; 16.7%; [Fig. 1]), followed by sarcoma, not otherwise specified (n = 4; 13.3%). Over 60% of patients had metastatic disease upon participation (n = 19). Twenty-five patients (83.3%) underwent tumor genomic interrogation via both DNA and RNA sequencing, while five patients (16.7%) had DNA sequencing done only as RNA sequencing failed due to the sample quality.

|

Characteristics |

Estimates[a] |

|---|---|

|

Age (y) |

42.5 (21–77) |

|

Sex |

|

|

Male |

10 (33.3) |

|

Female |

20 (66.7) |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

Malay |

3 (10.0) |

|

Chinese |

25 (83.3) |

|

Indian |

2 (6.7) |

|

Sarcoma types |

|

|

Soft tissue |

26 (86.7) |

|

Bone |

4 (13.3) |

|

Histologic subtypes |

|

|

Leiomyosarcoma |

5 (16.7) |

|

Sarcoma (NOS) |

4 (13.3) |

|

Epithelioid sarcoma |

3 (10.0) |

|

Angiosarcoma |

2 (6.7) |

|

Liposarcoma |

2 (6.7) |

|

Fibrosarcoma |

2 (6.7) |

|

Osteosarcoma |

2 (6.7) |

|

Rhabdomyosarcoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Ewing's Sarcoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Synovial sarcoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Carcinosarcoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Chondrosarcoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Clear cell sarcoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Myxofibrosarcoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Chordoma |

1 (3.3) |

|

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

1 (3.3) |

|

Solitary fibrous tumor |

1 (3.3) |

|

Metastatic disease |

|

|

Yes |

19 (63.3) |

|

No |

11 (36.7) |

|

Genome sequencing |

|

|

DNA and RNA analyses |

25 (83.3%) |

|

DNA only analysis |

5 (16.7%) |

Abbreviation: NOS, not otherwise specified.

a Estimates are reported as median (range) for age and N (%) for categorical variables.

Fig 1: Leiomyosarcoma showing cellular tumor composed of spindle cells that are haphazardly arranged. The nuclei show varying degrees of pleomorphism, and numerous mitotic figures (red arrows) are present (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×20 objective).

Genomic Profile

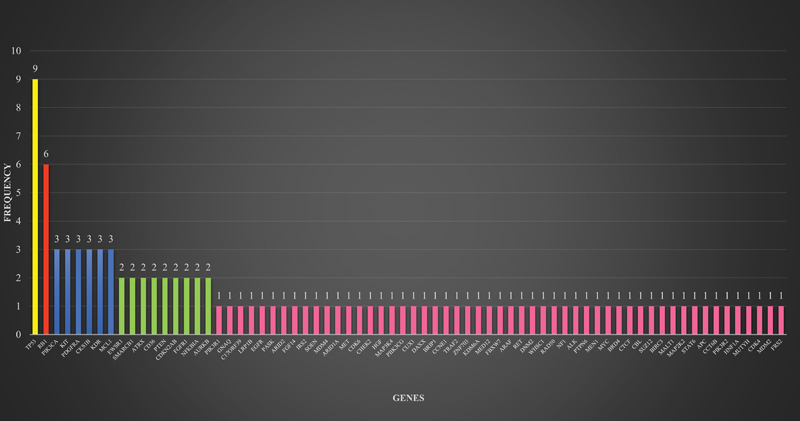

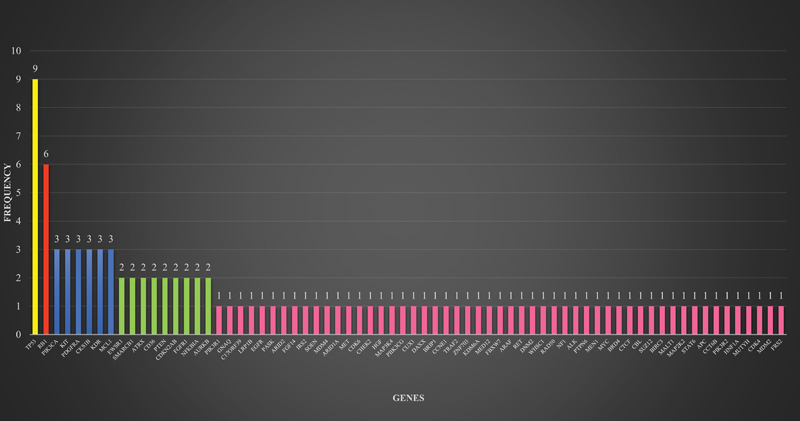

All patients in this study harbored at least one genetic mutation. The number of genetic mutations found in each patient ranged from 1 to 12, with an average of 3.5. The majority of patients had three or more coexisting genetic mutations (n = 16; 53.3%). The frequency, distribution and type of genomic aberrations are illustrated in [Fig. 2] and [Table 2]. A total of 70 genes were found to harbor mutations. The most frequently involved gene was TP53 (30.0%), followed by RB1 (20.0%), PIK3CA (10.0%), KIT (10.0%), PDGFRA (10.0%), CKS1B (10.0%), KDR (10.0%), and MCL1 (10.0%). Genomic alteration involving the ALK gene was the only targetable mutation identified. The DCTN1–ALK fusion was found to be targetable using entrectinib in this study.

Fig 2 : Frequency and distribution of genomic alterations in sarcoma patients.

|

Genes |

Types of mutation |

|---|---|

|

TP53 |

C229fs*10, L194R, E346fs*24, loss, splice site 994–1G > A, R273C, P152L, H193P |

|

RB1 |

Loss, R320, L477fs*18, loss exons 1–17, deletion exons 4–17, loss exons 3–27 |

|

PIK3CA |

V344G, G118D, C378Y |

|

KIT |

Amplification |

|

PDGFRA |

Amplification |

|

CKS1B |

Amplification |

|

KDR |

Amplification |

|

MCL1 |

Amplification |

|

EWSR1 |

EWSR1-FLI1 fusion, EWSR1-CREB3L1 fusion |

|

SMARCB1 |

E280, loss |

|

ATRX |

Q883fs*13, T1239fs*9 |

|

CD36 |

T111fs*22, Q74 |

|

PTEN |

Loss exons 1–2, C136R |

|

CDKN2A/B |

Loss |

|

FGFR1 |

N546K, amplification |

|

NFKBIA |

R17fs*69, amplification |

|

AURKB |

Amplification |

|

PIK3R1 |

G376R |

|

GNAQ |

R183Q |

|

C17orf39 |

Amplification |

|

LRP1B |

R902S |

|

EGFR |

P753S |

|

PASK |

R1267 |

|

ARID2 |

Rearrangement exon 21 |

|

FGF14 |

Amplification |

|

IRS2 |

Amplification |

|

SOEN |

Rearrangement exon 11 |

|

MDM4 |

Amplification |

|

ARID1A |

Q510 |

|

MET |

Amplification |

|

CDK6 |

Amplification |

|

CHEK2 |

Q487 |

|

HGF |

Amplification |

|

MAP3K4 |

Rearrangement exon 21 |

|

PIIK3CG |

Amplification |

|

CUX1 |

Splice site 1516–1G > A |

|

DAXX |

Rearrangement exon 2 |

|

BRIP1 |

Rearrangement intron 4 |

|

CCNE1 |

Amplification |

|

TRAF2 |

Rearrangement exon 2 |

|

ZNF703 |

Amplification |

|

KDM6A |

S700fs*29 |

|

MED12 |

G44C |

|

FBXW7 |

R505C |

|

ARAF |

R188H |

|

RET |

R813W |

|

DNM2 |

Deletion exons 2–11 |

|

WHSC1 (MMSET) |

E1099K |

|

RAD50 |

E723fs*5 |

|

NF1 |

S1100 |

|

ALK |

DCTN1-ALK fusion |

|

PTPN6 |

R554C |

|

MEN1 |

R521fs*15 |

|

MYC |

Amplification |

|

BRD4 |

Amplification |

|

CTCF |

Rearrangement exon 11 |

|

CBL |

Y371N |

|

SUZ12 |

Rearrangement intron 4 |

|

BIRC3 |

Loss |

|

MALT1 |

Amplification |

|

MAP2K2 (MEK2) |

Amplification |

|

STAT6 |

NAB2–STAT6 fusion |

|

APC |

C2042fs*2 |

|

CCT6B |

I4V |

|

PIK3R2 |

D163fs*24 |

|

HNF1A |

R131W |

|

MUTYH |

Splice site 892–2A > G |

|

CDK4 |

Amplification |

|

MDM2 |

Amplification |

|

FRS2 |

Amplification |

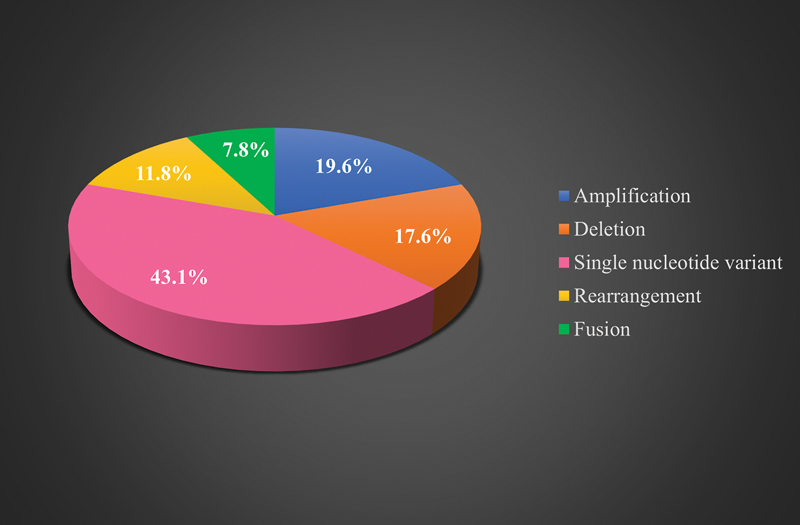

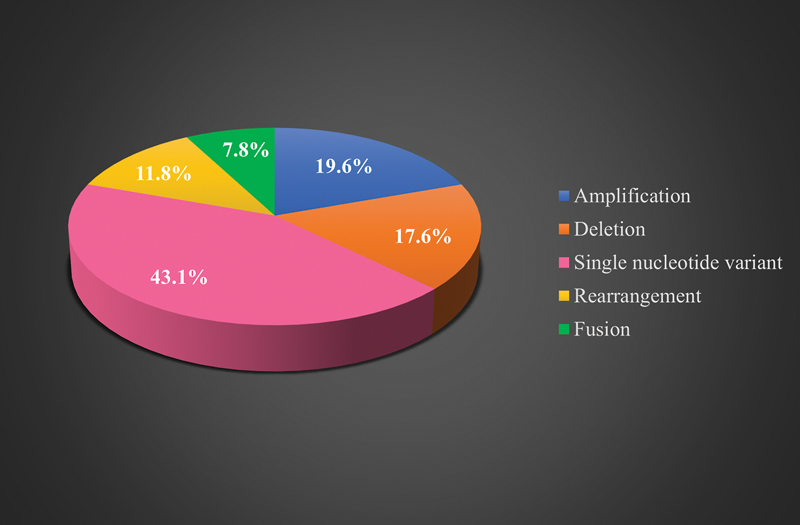

Fig 3 : Types of genomic aberrations in sarcoma patients.

Microsatellite status could not be determined in 2 patients, while the other 28 patients had microsatellite-stable tumors. Tumor mutational burden ranged from 0 to 7 mutations per megabase with an average of 3.0.

Discussion

Conclusion

This study shows that sarcomas do carry genetic mutations, some of which are targetable. Although the number of actionable variants identified remains limited, such data will be crucial for the selection of patients into clinical trials on novel therapies in the future and for establishing prognostic biomarkers. An understanding of the type and prevalence of mutations in sarcoma patients may guide treatment decisions and facilitate prognostication.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their patients for consenting to participate in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data (i.e., FoundationOne Heme test results) used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors' Contributions

G.F.H. designed, conducted, and supervised the study. E.V.C. conducted the literature search and drafted and edited the manuscript. W.Y.C. performed data collection and assisted the patients in the enrollment process. K.S.M. reviewed and prepared the patients' tumor samples to ensure quality control standards were met for genomic profiling. R.A.M. was involved in patient recruitment. M.S. was involved in patient recruitment.

All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Each named author has substantially contributed to conducting this study and the writing of this article. This manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all the coauthors.

Patient's Consent

Written, informed consent was taken from each participant after explanation of the aims, methods, and anticipated benefits of the study.

References

- Schöffski P, Cornillie J, Wozniak A, Li H, Hompes D. Soft tissue sarcoma: an update on systemic treatment options for patients with advanced disease. Oncol Res Treat 2014; 37 (06) 355-362

- Jo VY, Fletcher CDM. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology 2014; 46 (02) 95-104

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Survival Rates for Soft Tissue Sarcoma. 2021. Accessed June 25, 2024 at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Survival Rates for Osteosarcoma. 2023. Accessed June 25, 2024 at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/osteosarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

- Prendergast SC, Strobl AC, Cross W. et al; RNOH Pathology Laboratory and Biobank Team, Genomics England Research Consortium. Sarcoma and the 100,000 Genomes Project: our experience and changes to practice. J Pathol Clin Res 2020; 6 (04) 297-307

- Bui NQ, Przybyl J, Trabucco SE. et al. A clinico-genomic analysis of soft tissue sarcoma patients reveals CDKN2A deletion as a biomarker for poor prognosis. Clin Sarcoma Res 2019; 9: 12

- Lovly CM, Gupta A, Lipson D. et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors harbor multiple potentially actionable kinase fusions. Cancer Discov 2014; 4 (08) 889-895

- Davis LE, Nusser KD, Przybyl J. et al. Discovery and characterization of recurrent, targetable ALK fusions in leiomyosarcoma. Mol Cancer Res 2019; 17 (03) 676-685

- Hallberg B, Palmer RH. The role of the ALK receptor in cancer biology. Ann Oncol 2016; 27 (Suppl. 03) iii4-iii15

- Drilon A, Siena S, Ou SI. et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the multitargeted pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor entrectinib: combined results from two phase I trials (ALKA-372-001 and STARTRK-1). Cancer Discov 2017; 7 (04) 400-409

- Patel MR, Bauer TM, Liu SV. et al. STARTRK-1: phase 1/2a study of entrectinib, an oral Pan-Trk, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors with relevant molecular alterations. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2596

- Braud FGD, Niger M, Damian S. et al. Alka-372–001: first-in-human, phase I study of entrectinib—an oral pan-trk, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor—in patients with advanced solid tumors with relevant molecular alterations. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2517

- Multani P, Manavel EC, Hornby Z. et al. Preliminary evidence of clinical response to entrectinib in three sarcoma patients. Paper presented at: 2017 Connective Tissue Oncology Society Annual Meeting; November 8–11, 2017; Maui, Hawaii

- Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E. et al. RECIST 1.1-update and clarification: from the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer 2016; 62: 132-137

- Meijer D, de Jong D, Pansuriya TC. et al. Genetic characterization of mesenchymal, clear cell, and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012; 51 (10) 899-909

- Pérot G, Chibon F, Montero A. et al. Constant p53 pathway inactivation in a large series of soft tissue sarcomas with complex genetics. Am J Pathol 2010; 177 (04) 2080-2090

- Koehler K, Liebner D, Chen JL. TP53 mutational status is predictive of pazopanib response in advanced sarcomas. Ann Oncol 2016; 27 (03) 539-543

- Engel BE, Cress WD, Santiago-Cardona PG. The retinoblastoma protein: a master tumor suppressor acts as a link between cell cycle and cell adhesion. Cell Health Cytoskelet 2015; 7: 1-10

- Kleinerman RA, Schonfeld SJ, Tucker MA. Sarcomas in hereditary retinoblastoma. Clin Sarcoma Res 2012; 2 (01) 15

- Liu Y, Sánchez-Tilló E, Lu X. et al. Rb1 family mutation is sufficient for sarcoma initiation. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2650

- Pandey P, Khan F, Upadhyay TK, Seungjoon M, Park MN, Kim B. New insights about the PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway as a promising target to develop cancer therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother 2023; 161: 114491

- Cassier PA, Fumagalli E, Rutkowski P. et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Outcome of patients with platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha-mutated gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18 (16) 4458-4464

- von Mehren M, Heinrich MC, Shi H. et al. Clinical efficacy comparison of avapritinib with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors in gastrointestinal stromal tumors with PDGFRA D842V mutation: a retrospective analysis of clinical trial and real-world data. BMC Cancer 2021; 21 (01) 291

- FDA. Approval Package for AYVAKIT (avapritinib). 2023. Accessed June 25, 2024 at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/212608Orig1s013.pdf

- Heinrich MC, Jones RL, von Mehren M. et al. Avapritinib in advanced PDGFRA D842V-mutant gastrointestinal stromal tumour (NAVIGATOR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21 (07) 935-946

- Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11 (12) 865-878

- Wei H, Zhao MQ, Dong W, Yang Y, Li JS. Expression of c-kit protein and mutational status of the c-kit gene in osteosarcoma and their clinicopathological significance. J Int Med Res 2008; 36 (05) 1008-1014

- Entz-Werlé N, Marcellin L, Gaub M-P. et al. Prognostic significance of allelic imbalance at the c-kit gene locus and c-kit overexpression by immunohistochemistry in pediatric osteosarcomas. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23 (10) 2248-2255

- Handolias D, Hamilton AL, Salemi R. et al. Clinical responses observed with imatinib or sorafenib in melanoma patients expressing mutations in KIT. Br J Cancer 2010; 102 (08) 1219-1223

- Minor DR, Kashani-Sabet M, Garrido M, O'Day SJ, Hamid O, Bastian BC. Sunitinib therapy for melanoma patients with KIT mutations. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18 (05) 1457-1463

- André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G. et al; SOLAR-1 Study Group. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 380 (20) 1929-1940

- Schmid P, Abraham J, Chan S. et al. Capivasertib plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: the PAKT trial. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38 (05) 423-433

- Barretina J, Taylor BS, Banerji S. et al. Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nat Genet 2010; 42 (08) 715-721

- Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D. et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 2017; 9 (01) 34

- Monument MJ, Lessnick SL, Schiffman JD, Randall RT. Microsatellite instability in sarcoma: fact or fiction?. ISRN Oncol 2012; 2012: 473146

- Lam SW, Kostine M, de Miranda NFCC. et al. Mismatch repair deficiency is rare in bone and soft tissue tumors. Histopathology 2021; 79 (04) 509-520

- Fernandes I, Dias E Silva D, Segatelli V. et al. Microsatellite instability and clinical use in sarcomas: systematic review and illustrative case report. JCO Precis Oncol 2024; 8: e2400047

- Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN. et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet 2019; 51 (02) 202-206

Address for correspondence

Publication History

03 March 2025

© 2025. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Adult Soft Tissue Sarcoma: A Prospective Observational Real-World DataShivashankara Mathighatta Shivarudraiah, Indian J Radiol Imaging, 2021

- Toward a Better Understanding of the Use of Targeted Therapies in Pediatric Sarcoma PatientsLars M. Wagner, Journal of Pediatric Biochemistry, 2016

- Analysis of Dedifferentiated Liposarcomas Emphasizing the Diagnostic DilemmasBhagat Singh Lali, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2020

- Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy versus fine-needle aspiration for genomic profiling and DNA yield in pancreatic cancer: a randomiz...Pujan Kandel, Zentralblatt für Chirurgie - Zeitschrift für Allgemeine, Viszeral-, Thorax- und Gefäßchirurgie

- Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy versus fine-needle aspiration for genomic profiling and DNA yield in pancreatic cancer: a randomiz...Pujan Kandel, Endoscopy

- BRAF and MEK Inhibitor Treatment for Metastatic Undifferentiated Sarcoma of the Spermatic Cord with BRAF V600E Mutation<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> Ken Saijo, Case Reports in Oncology, 2022 - A Pan-Cancer Landscape Analysis Reveals a Subset of Endometrial Stromal and Pediatric Tumors Defined by Internal Tandem Duplications of BCORLuke T. Juckett, Oncology, 2019

- Sequencing PEComas: Viewing Unicorns through the Molecular Looking Glass<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> Roman Groisberg, Oncology, 2021 - Activity of c-Met/ALK Inhibitor Crizotinib and Multi-Kinase VEGF Inhibitor Pazopanib in Metastatic Gastrointestinal Neuroectodermal Tumor Harboring EWSR1-CREB1 ...<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> Vivek Subbiah, Oncology, 2016 - Breast Cancer Patients' Views on the Use of Genomic Testing to Guide Decisions about Their Postoperative ChemotherapyV. Seror, Community Genetics, 2013

Fig 1: Leiomyosarcoma showing cellular tumor composed of spindle cells that are haphazardly arranged. The nuclei show varying degrees of pleomorphism, and numerous mitotic figures (red arrows) are present (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×20 objective).

Fig 2 : Frequency and distribution of genomic alterations in sarcoma patients.

Fig 3 : Types of genomic aberrations in sarcoma patients.

References

- Schöffski P, Cornillie J, Wozniak A, Li H, Hompes D. Soft tissue sarcoma: an update on systemic treatment options for patients with advanced disease. Oncol Res Treat 2014; 37 (06) 355-362

- Jo VY, Fletcher CDM. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology 2014; 46 (02) 95-104

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Survival Rates for Soft Tissue Sarcoma. 2021. Accessed June 25, 2024 at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Survival Rates for Osteosarcoma. 2023. Accessed June 25, 2024 at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/osteosarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

- Prendergast SC, Strobl AC, Cross W. et al; RNOH Pathology Laboratory and Biobank Team, Genomics England Research Consortium. Sarcoma and the 100,000 Genomes Project: our experience and changes to practice. J Pathol Clin Res 2020; 6 (04) 297-307

- Bui NQ, Przybyl J, Trabucco SE. et al. A clinico-genomic analysis of soft tissue sarcoma patients reveals CDKN2A deletion as a biomarker for poor prognosis. Clin Sarcoma Res 2019; 9: 12

- Lovly CM, Gupta A, Lipson D. et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors harbor multiple potentially actionable kinase fusions. Cancer Discov 2014; 4 (08) 889-895

- Davis LE, Nusser KD, Przybyl J. et al. Discovery and characterization of recurrent, targetable ALK fusions in leiomyosarcoma. Mol Cancer Res 2019; 17 (03) 676-685

- Hallberg B, Palmer RH. The role of the ALK receptor in cancer biology. Ann Oncol 2016; 27 (Suppl. 03) iii4-iii15

- Drilon A, Siena S, Ou SI. et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the multitargeted pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor entrectinib: combined results from two phase I trials (ALKA-372-001 and STARTRK-1). Cancer Discov 2017; 7 (04) 400-409

- Patel MR, Bauer TM, Liu SV. et al. STARTRK-1: phase 1/2a study of entrectinib, an oral Pan-Trk, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors with relevant molecular alterations. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2596

- Braud FGD, Niger M, Damian S. et al. Alka-372–001: first-in-human, phase I study of entrectinib—an oral pan-trk, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor—in patients with advanced solid tumors with relevant molecular alterations. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2517

- Multani P, Manavel EC, Hornby Z. et al. Preliminary evidence of clinical response to entrectinib in three sarcoma patients. Paper presented at: 2017 Connective Tissue Oncology Society Annual Meeting; November 8–11, 2017; Maui, Hawaii

- Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E. et al. RECIST 1.1-update and clarification: from the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer 2016; 62: 132-137

- Meijer D, de Jong D, Pansuriya TC. et al. Genetic characterization of mesenchymal, clear cell, and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012; 51 (10) 899-909

- Pérot G, Chibon F, Montero A. et al. Constant p53 pathway inactivation in a large series of soft tissue sarcomas with complex genetics. Am J Pathol 2010; 177 (04) 2080-2090

- Koehler K, Liebner D, Chen JL. TP53 mutational status is predictive of pazopanib response in advanced sarcomas. Ann Oncol 2016; 27 (03) 539-543

- Engel BE, Cress WD, Santiago-Cardona PG. The retinoblastoma protein: a master tumor suppressor acts as a link between cell cycle and cell adhesion. Cell Health Cytoskelet 2015; 7: 1-10

- Kleinerman RA, Schonfeld SJ, Tucker MA. Sarcomas in hereditary retinoblastoma. Clin Sarcoma Res 2012; 2 (01) 15

- Liu Y, Sánchez-Tilló E, Lu X. et al. Rb1 family mutation is sufficient for sarcoma initiation. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2650

- Pandey P, Khan F, Upadhyay TK, Seungjoon M, Park MN, Kim B. New insights about the PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway as a promising target to develop cancer therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother 2023; 161: 114491

- Cassier PA, Fumagalli E, Rutkowski P. et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Outcome of patients with platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha-mutated gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18 (16) 4458-4464

- von Mehren M, Heinrich MC, Shi H. et al. Clinical efficacy comparison of avapritinib with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors in gastrointestinal stromal tumors with PDGFRA D842V mutation: a retrospective analysis of clinical trial and real-world data. BMC Cancer 2021; 21 (01) 291

- FDA. Approval Package for AYVAKIT (avapritinib). 2023. Accessed June 25, 2024 at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/212608Orig1s013.pdf

- Heinrich MC, Jones RL, von Mehren M. et al. Avapritinib in advanced PDGFRA D842V-mutant gastrointestinal stromal tumour (NAVIGATOR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21 (07) 935-946

- Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11 (12) 865-878

- Wei H, Zhao MQ, Dong W, Yang Y, Li JS. Expression of c-kit protein and mutational status of the c-kit gene in osteosarcoma and their clinicopathological significance. J Int Med Res 2008; 36 (05) 1008-1014

- Entz-Werlé N, Marcellin L, Gaub M-P. et al. Prognostic significance of allelic imbalance at the c-kit gene locus and c-kit overexpression by immunohistochemistry in pediatric osteosarcomas. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23 (10) 2248-2255

- Handolias D, Hamilton AL, Salemi R. et al. Clinical responses observed with imatinib or sorafenib in melanoma patients expressing mutations in KIT. Br J Cancer 2010; 102 (08) 1219-1223

- Minor DR, Kashani-Sabet M, Garrido M, O'Day SJ, Hamid O, Bastian BC. Sunitinib therapy for melanoma patients with KIT mutations. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18 (05) 1457-1463

- André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G. et al; SOLAR-1 Study Group. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 380 (20) 1929-1940

- Schmid P, Abraham J, Chan S. et al. Capivasertib plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: the PAKT trial. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38 (05) 423-433

- Barretina J, Taylor BS, Banerji S. et al. Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nat Genet 2010; 42 (08) 715-721

- Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D. et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 2017; 9 (01) 34

- Monument MJ, Lessnick SL, Schiffman JD, Randall RT. Microsatellite instability in sarcoma: fact or fiction?. ISRN Oncol 2012; 2012: 473146

- Lam SW, Kostine M, de Miranda NFCC. et al. Mismatch repair deficiency is rare in bone and soft tissue tumors. Histopathology 2021; 79 (04) 509-520

- Fernandes I, Dias E Silva D, Segatelli V. et al. Microsatellite instability and clinical use in sarcomas: systematic review and illustrative case report. JCO Precis Oncol 2024; 8: e2400047

- Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN. et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet 2019; 51 (02) 202-206

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share