Trends of Oral Cancer with Regard to Age, Gender, and Subsite Over 16 Years at a Tertiary Cancer Center in India

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2018; 39(03): 297-300

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_6_17

Abstract

Introduction: Oral cancers are among the most common cancers in the Indian subcontinent and tobacco is the most common implicated etiologic agent for these cancers. Over last two decades, significant changes have occurred in the lifestyle of people in the subcontinent. Antitobacco legislations have made developed and awareness about the harmful effects of tobacco and related products have increased. We hypothesized that this would lead to change in tobacco use pattern and hence impact the trends of oral cancer in India. Methodology: We analyzed the hospital records of patients having buccal mucosa and tongue cancers at a tertiary care cancer center. We noted the trends of patients presenting with these cancers 4 yearly, over a period of 16 years and in this way tried to assess the impact of legislation and awareness activities upon cancer incidence and trends. Results:: This study has shown that the number of patients presenting with tongue and buccal mucosa cancers has not decreased over the years. Increase in buccal mucosa cancers is marginally more than that of the tongue cancer. Proportion of males with respect to females presenting with these cancers has increased. There has been no significant decline in the younger patients presenting with these cancers. Common age of presentation of tongue cancers has come down. Conclusion: The findings of this study highlight the ineffectiveness of current laws and awareness programs in reducing the menace of oral cancer.

Keywords

Antitobacco legislation - buccal mucosa cancer - India - oral cancer - tongue cancer - trendsPublication History

Article published online:

17 June 2021

© 2018. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Introduction: Oral cancers are among the most common cancers in the Indian subcontinent and tobacco is the most common implicated etiologic agent for these cancers. Over last two decades, significant changes have occurred in the lifestyle of people in the subcontinent. Antitobacco legislations have made developed and awareness about the harmful effects of tobacco and related products have increased. We hypothesized that this would lead to change in tobacco use pattern and hence impact the trends of oral cancer in India. Methodology: We analyzed the hospital records of patients having buccal mucosa and tongue cancers at a tertiary care cancer center. We noted the trends of patients presenting with these cancers 4 yearly, over a period of 16 years and in this way tried to assess the impact of legislation and awareness activities upon cancer incidence and trends. Results:: This study has shown that the number of patients presenting with tongue and buccal mucosa cancers has not decreased over the years. Increase in buccal mucosa cancers is marginally more than that of the tongue cancer. Proportion of males with respect to females presenting with these cancers has increased. There has been no significant decline in the younger patients presenting with these cancers. Common age of presentation of tongue cancers has come down. Conclusion: The findings of this study highlight the ineffectiveness of current laws and awareness programs in reducing the menace of oral cancer.

Keywords

Antitobacco legislation - buccal mucosa cancer - India - oral cancer - tongue cancer - trendsIntroduction

Oral cancers are among the most common cancers in the Indian subcontinent.[1] Tobacco use is very common in Indian subcontinent, and it is the most common implicated etiologic agent for these cancers. Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA) was introduced in 2003 in India. It banned smoking at public places, sale of tobacco, and related products to children <18>

Methodology

This was a retrospective analysis of hospital records in a tertiary care apex referral cancer center from 1996 to 2012. Data of patients diagnosed as having oral tongue cancer and buccal mucosa cancer were collected from the hospital records. As the study involved analyzing of previously collected hospital records, no institutional review board approval was sought for. Demographic data including the age at presentation and gender of these patients were noted. These data were collected and documented in a tabular manner and the trends were depicted graphically and also through tables. These were then analyzed to look for any changes which have occurred over 16 years.

Results

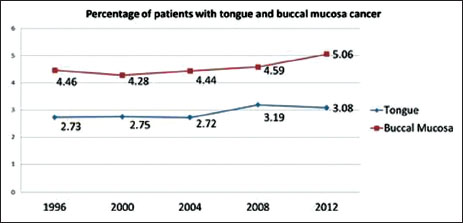

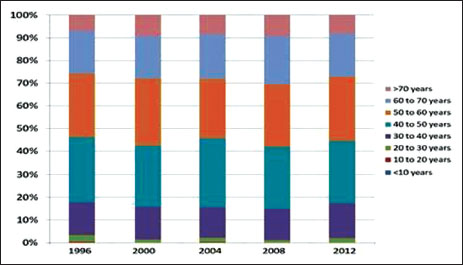

This study evaluated the cancer patients presenting to a tertiary care referral cancer center in India. The trends of tongue and buccal mucosa cancer were observed 4 yearly for 16 years from 1996 to 2004. The total numbers of cancer patients registered at the hospital during these years are mentioned in [Table 1]. There has been increase in the number of patients being registered with about 11,000 more number of patients being registered in 2012 as compared to 1996.

|

Year |

Total cancer patients registered |

Number of patients having tongue cancer |

Percentage of patients having tongue cancer |

Number of patients having buccal mcosa cancer |

Percentage of patients having buccal mucosa cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1996 |

14403 |

393 |

2.73 |

643 |

4.46 |

|

2000 |

15591 |

429 |

2.75 |

668 |

4.28 |

|

2004 |

17163 |

468 |

2.72 |

762 |

4.44 |

|

2008 |

21711 |

693 |

3.19 |

997 |

4.59 |

|

2012 |

25533 |

787 |

3.08 |

1293 |

5.06 |

| Figure.1:Time trends of tongue and buccal mucosa cancer

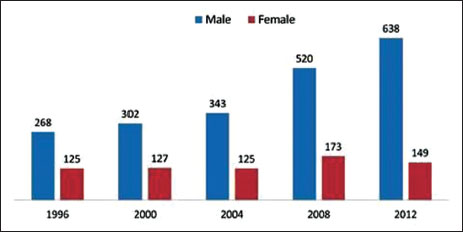

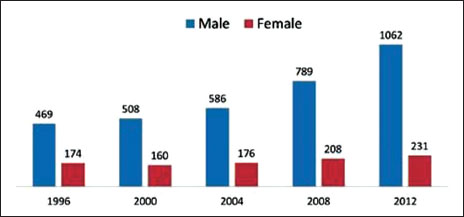

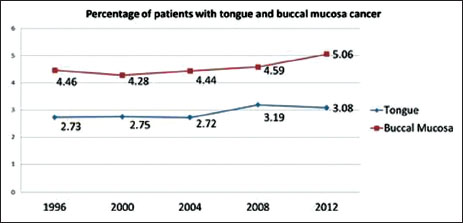

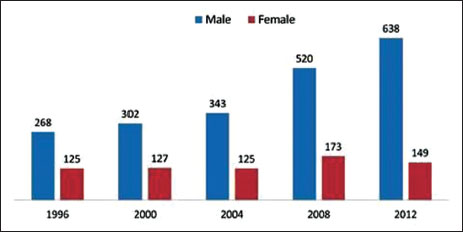

We analyzed the gender-wise distribution of the patients. In patients having tongue cancer, male to female ratio was 2.14 in 1996. The gap between males and females widened and the male to female ratio increased to 4.28 in 2012. In patients having buccal mucosa cancer, male to female ratio in 1996 was 2.69 and it increased to 4.59 in 2012. These are depicted in [Figure 2] and [Figure 3].

| Figure.2Gender distribution of tongue cancer patients

| Figure.3Gender distribution of buccal mucosa cancer patients

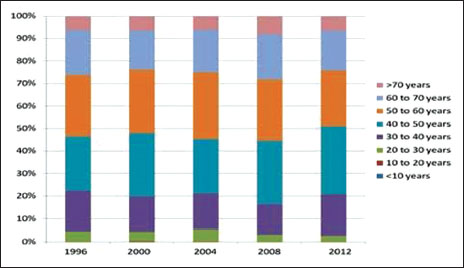

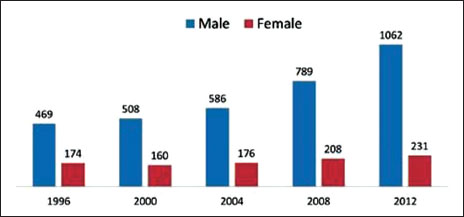

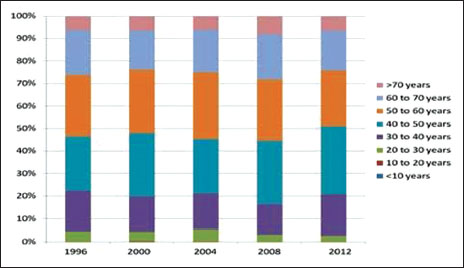

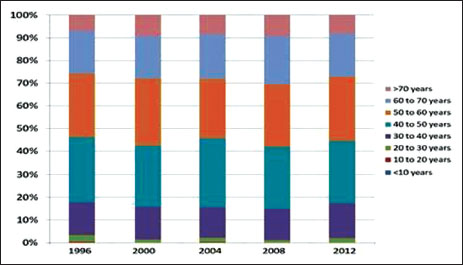

Age group-wise yearly distribution of the patients was also studied. It was found to be similar for both tongue as well as buccal mucosa cancer. No significant change in the age distribution was noticed from 1996 to 2012. Details are given in [Table 2] and [Table 3]. The trends are depicted in [Figure 4] and [Figure 5].

|

Year |

1996 |

2000 |

2004 |

2008 |

2012 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age group (years) |

T |

% |

T |

% |

T |

% |

T |

% |

T |

% |

|

<10> |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

10-20 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.2 |

1 |

0.2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.1 |

|

20-30 |

18 |

4.5 |

18 |

4.2 |

24 |

5.1 |

21 |

3 |

21 |

2.7 |

|

30-40 |

70 |

17.8 |

66 |

15.4 |

74 |

15.8 |

92 |

13.4 |

143 |

18.1 |

|

40-50 |

95 |

24.1 |

121 |

28.2 |

113 |

24.1 |

193 |

28.1 |

238 |

30.2 |

|

50-60 |

107 |

27.2 |

121 |

28.2 |

139 |

29.7 |

187 |

27.2 |

196 |

24.8 |

|

60-70 |

79 |

20.1 |

75 |

17.4 |

88 |

18.8 |

139 |

20.2 |

139 |

17.6 |

|

>70 |

24 |

6.1 |

27 |

6.3 |

29 |

6.2 |

55 |

8 |

51 |

6.5 |

|

Year |

1996 |

2000 |

2004 |

2008 |

2012 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age group (years) |

T |

% |

T |

% |

T |

% |

T |

% |

T |

% |

|

<10> |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.1 |

0 |

0 |

|

10-20 |

3 |

0.5 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0.2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.07 |

|

20-30 |

20 |

3.1 |

10 |

1.5 |

15 |

2 |

11 |

1.1 |

25 |

1.9 |

|

30-40 |

92 |

14.3 |

98 |

14.4 |

103 |

13.5 |

137 |

13.7 |

198 |

15.4 |

|

40-50 |

182 |

28.3 |

180 |

26.5 |

229 |

30 |

269 |

27 |

348 |

27 |

|

50-60 |

180 |

28 |

200 |

29.5 |

198 |

26 |

274 |

27.4 |

365 |

28.3 |

|

60-70 |

122 |

19 |

128 |

18.8 |

152 |

20 |

213 |

21.3 |

245 |

19 |

|

>70 |

44 |

6.8 |

62 |

9.1 |

63 |

8.2 |

92 |

9.2 |

104 |

8 |

| Figure.4:Age group-wise yearly distribution of tongue cancer patients

| Figure.5Age group-wise yearly distribution of buccal mucosa cancer patients

Discussion

Oral cancers are among the most common cancers in the Indian subcontinent.[1] Tobacco (both chewable and nonchewable) is responsible for the majority of oral cancers. According to Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 34.6% of adults in India; including 47.9% of males and 20.3% of females consume tobacco. Among these, 14% of adults smoke tobacco whereas 25.9% consume smokeless tobacco.[2] Global Youth Tobacco Survey assessed the use of tobacco in Indian children of the age group 13–15 years. It found that 14.6% of these children had used tobacco products (boy = 19.0%, girl = 8.3%). 4.4% smoked cigarettes (boy 5.8%, girl 2.4%), 12.5% currently used tobacco products other than manufactured cigarettes (boys 16.2%, girl 7.2%). Smokeless tobacco usage in these children has been shown to be about 9% (boys 11.1%, girls 6%). These percentages show a high prevalence of tobacco use in the children as well as adults.[3],[4] COTPA was introduced in 2003 in India.[5] India also became part of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.[6] This legislation banned smoking in public places and illegalized sale of tobacco to minors and near educational institutions. Prohibition was put on advertising through media. Laws were also framed regarding pictorial and textual warnings, along with this antitobacco advertisements were also displayed in movie halls and in television.

As per National Family Health Survey-4,[7],[8] tobacco and alcohol use among men has fallen down from 50%–47% to 38%–34%, respectively, over the last decade. In a study on the trends of head neck cancers in India, it was observed that incidence of tongue cancer is decreasing and the incidence of other oral cancer is stable or increasing as per different cancer registries.[9] In Indian subcontinent, there are more number of people who are tobacco chewers as compared to smokers. Chewing tobacco more often results in buccal mucosa and lower alveolus cancer whereas smoking and alcohol consumption has been associated with higher incidence of tongue cancer. We had hypothesized that over the recent years with increasing influence of the western culture, there may be a change in tobacco and alcohol use pattern and there by a rising trend of tongue cancers due to more number of people switching over to smoking. We also wanted to see if due to early onset of tobacco use, whether the number of younger patients presenting with cancer had increased or if the changing addiction habits had an impact upon gender-specific incidence of oral cancers. With legislations, educational drives for increasing awareness about harmful effects of cancer and higher taxes on tobacco-related products, we expected to have some changes in incidence of oral cancer and in its demographic profile. Oral cancer is the most common tobacco-related cancer in India and among oral cancers, tongue and buccal mucosa cancers are the most common. Hence, we decided to observe the trend of patients presenting with these cancers every 4 years from the year 1996–2012.

In our study, we found that over the years, there was increase in the percentage of patients having tongue and buccal mucosa cancer. The increase in buccal mucosa cancer was 0.6% as compared to that of tongue which was 0.35%. This was contrary to our hypothesis that incidence of tongue cancers has increased more than that of buccal mucosa cancers. This probably indirectly demonstrates that in Indian subcontinent, chewing tobacco still remains the most common addiction.

Gender-wise distribution of the tongue and buccal mucosa cancers did not show any significant change over the years. Both the subsites showed similar male-to-female ratio thereby signifying that there was no significant gender-specific difference between the two subsites. For both tongue and buccal mucosa cancer, male-to-female ratio has increased over the years. It was 2.14 and 2.69 in 1996, and it increased to 4.28 and 4.59 in 2012, respectively. The number of male patients has increased 2 folds as compared to the female patients. This shows that though the actual numbers of female cancer patients has risen, still the problem remains much more extensive amongst the males.

On studying the age-wise distribution of these cancers, a few changes were seen over the years. Majority of the patients (about 55%) presented between the ages of 40–60 years. It was observed that the most common age of presentation of tongue cancers came down from 50–60 years in 1996 to 40–50 years in 2012. No such change was noted for buccal mucosa cancer. There was no decrease in incidence observed in the younger age group. Although a very small decrease in incidence in the age group of 30–40 years was seen, in cases of tongue cancer from 4.5% to 2.7% and in buccal mucosa cancer from 3.1 and to 1.9%. However, no meaningful conclusion can be drawn from such a minimalistic decrease.

The data show a trend of over 16 years from 1996 to 2012. This period has seen significant changes in the lifestyle of the population and in tobacco-related legislations. This study was a retrospective study done by assessing the hospital records at a tertiary care referral cancer center. The data analyzed are that of the patients who presented to this single center and it is not of a population-based cancer registry. Still, it is a good depiction of the general trends because the center gets referred patients from all over the subcontinent.

Conclusion

This study has shown that the number of patients presenting with tongue and buccal mucosa cancers has not decreased over the years. Increase in buccal mucosa cancers is marginally more than that of the tongue cancer. Proportion of males with respect to females presenting with these cancers has increased. There has been no significant decline in the younger patients presenting with these cancers. Common age of presentation of tongue cancers has come down. These findings highlight the persistent effects of rampant tobacco use in the Indian subcontinent and the ineffectiveness of antitobacco awareness activities and enforcement of tobacco-related legislations.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C. et al.GLOBOCAN 2012 Ver. 1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01]

- International Institute for Population Sciences, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Global Adult Tobacco Survey India (GATS India), 2009-2010. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2010. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/en/Section20/Section25_1861.htm. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- Sinha DN, Palipudi KM, Rolle I, Asma S, Rinchen S. Tobacco use among youth and adults in member countries of South-East Asia region: Review of findings from surveys under the Global Tobacco Surveillance System. Indian J Public Health 2011; 55: 169-76

- Sinha DN, Palipudi KM, Jones CK, Khadka BB, Silva PD, Mumthaz M. et al. Levels and trends of smokeless tobacco use among youth in countries of the World Health Organization South-East Asia Region. Indian J Cancer 2014; 51 Suppl 1: S50-3

- The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003; An Act enacted by the Parliament of Republic of India by Notification in the Official Gazette. (Act 32 of 2003) Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/index1.php?lang&level=2&sublinkid=671&lid=662. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/en/Section20/Section25_927.htm. [Last accessed on 2013 Jun 06].

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-4, State Fact Sheet Madhya Pradesh, 2015-2016: India, Mumbai: IIPS; 2016. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/NFHS/pdf/NFHS4/MP_FactSheet.pdf. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-4, State Fact Sheet Bihar, 2015-2016: India, Mumbai: IIPS; 2016. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/NFHS/pdf/NFHS4/BR_FactSheet.pdf. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- Yeole BB. Trends in incidence of head and neck cancers in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2007; 8: 607-12

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

17 June 2021

© 2018. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2,

Noida-201301 UP, India

| Figure.1:Time trends of tongue and buccal mucosa cancer

| Figure.2Gender distribution of tongue cancer patients

| Figure.3Gender distribution of buccal mucosa cancer patients

| Figure.4:Age group-wise yearly distribution of tongue cancer patients

| Figure.5Age group-wise yearly distribution of buccal mucosa cancer patients

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C. et al.GLOBOCAN 2012 Ver. 1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01]

- International Institute for Population Sciences, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Global Adult Tobacco Survey India (GATS India), 2009-2010. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2010. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/en/Section20/Section25_1861.htm. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- Sinha DN, Palipudi KM, Rolle I, Asma S, Rinchen S. Tobacco use among youth and adults in member countries of South-East Asia region: Review of findings from surveys under the Global Tobacco Surveillance System. Indian J Public Health 2011; 55: 169-76

- Sinha DN, Palipudi KM, Jones CK, Khadka BB, Silva PD, Mumthaz M. et al. Levels and trends of smokeless tobacco use among youth in countries of the World Health Organization South-East Asia Region. Indian J Cancer 2014; 51 Suppl 1: S50-3

- The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003; An Act enacted by the Parliament of Republic of India by Notification in the Official Gazette. (Act 32 of 2003) Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/index1.php?lang&level=2&sublinkid=671&lid=662. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/en/Section20/Section25_927.htm. [Last accessed on 2013 Jun 06].

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-4, State Fact Sheet Madhya Pradesh, 2015-2016: India, Mumbai: IIPS; 2016. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/NFHS/pdf/NFHS4/MP_FactSheet.pdf. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-4, State Fact Sheet Bihar, 2015-2016: India, Mumbai: IIPS; 2016. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/NFHS/pdf/NFHS4/BR_FactSheet.pdf. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 01].

- Yeole BB. Trends in incidence of head and neck cancers in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2007; 8: 607-12

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share