Tuberculosis of Frontal Bone—A Rare Entity: Case Report and Review of Literature

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025; 46(03): 332-336

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-1772234

Abstract

Tuberculosis of the frontal bone is a rare entity, most commonly occurring in childhood. In situations of painless scalp swelling coupled with or without a discharging sinus that has not responded to antibiotics, a strong index of suspicion must be raised. Generally, conventional radiography and computed tomography are used for establishing the diagnosis along with microbiological confirmation. We present an interesting case of a young boy who presented with a 2-month-old bone lesion in the frontal scalp, accompanied by mediastinal lymph node involvement. Histopathology revealed tuberculous origin and successful antitubercular therapy resulted in significant improvement within 3 months. The calvarial bones can rarely be affected by tuberculosis, which can present with swelling, sinus discharge, pain, or in rare cases as blindness. Prompt diagnosis of this disease is needed as it is potentially curable and has an excellent prognosis. The cornerstone of treatment is antitubercular therapy, while surgical intervention may sometimes be required. Our case highlights the importance of keeping tuberculosis as a differential at the back of the mind when dealing with scalp swellings, particularly in children.

Patient Consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Publication History

Article published online:

26 September 2023

© 2023. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Primary mandibular tuberculous osteomyelitis mimicking ameloblastoma: A case report and literature review of mandibular tuberculous osteomyelitisChandrashekhar Chalwade, Archives of Plastic Surgery

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Frontal Sinus Presenting as a Pott Puffy Tumor: Case ReportNickalus Khan, Journal of Neurological Surgery Reports, 2015

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Frontal Sinus Presenting as a Pott Puffy Tumor: Case ReportNickalus Khan, J Neurol Surg Rep, 2015

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Frontal Sinus Presenting as a Pott Puffy Tumor: Case ReportNickalus Khan, VCOT Open, 2015

- Concurrent Inverted Papilloma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Intradural Extension Presenting with Frontal Lobe SyndromeAbdul Jaleel, Indian Journal of Neurosurgery, 2021

- Note on the Cranial Characters of a large Teleosaur from the Whitby Lias preserved in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge, indicating a new Sp...<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- II. Description of the Human Skull and Mandible and the Associated Mammalian Remains. [A. S. W.]<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- On the Occurrence of Antelope remains in Newer Pliocene Beds in Britain, with the Description of a new Species, Gazella anglica<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- On the Skull of Argillornis longipennis, Ow.<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Entity Relationship Extraction from Text Data Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

Abstract

Tuberculosis of the frontal bone is a rare entity, most commonly occurring in childhood. In situations of painless scalp swelling coupled with or without a discharging sinus that has not responded to antibiotics, a strong index of suspicion must be raised. Generally, conventional radiography and computed tomography are used for establishing the diagnosis along with microbiological confirmation. We present an interesting case of a young boy who presented with a 2-month-old bone lesion in the frontal scalp, accompanied by mediastinal lymph node involvement. Histopathology revealed tuberculous origin and successful antitubercular therapy resulted in significant improvement within 3 months. The calvarial bones can rarely be affected by tuberculosis, which can present with swelling, sinus discharge, pain, or in rare cases as blindness. Prompt diagnosis of this disease is needed as it is potentially curable and has an excellent prognosis. The cornerstone of treatment is antitubercular therapy, while surgical intervention may sometimes be required. Our case highlights the importance of keeping tuberculosis as a differential at the back of the mind when dealing with scalp swellings, particularly in children.

Keywords

case report - tuberculosis - calvaria - CT - PET-CTIntroduction

Infection with mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) is still widespread in developing nations. With the resurgence of immunocompromised states like human immunodeficiency virus infection, malignancies, etc. there is a rise in the incidence of TB in developed countries. In the last 10 years, there has been a dramatic transformation in the clinical pattern and presentation of TB. Disseminated TB may occur either due to activation of a latent focus of infection or secondary to progressive primary pulmonary TB. The tubercular bacilli are said to erode the epithelial layer of the alveoli, and enter the pulmonary vein. Following this, they enter the left side of the heart, and get disseminated into the systemic circulation thereby reaching bones, kidneys, brain, and other organs. Only 0.2 to 1.3%-of skeletal TB cases involve calvarial bones, which is almost always secondary to disseminated TB. The first case was reported in Germany by Reid.[1] Strauss reported 220 cases in 1933.[2] Meng and Wu reported 40 cases.[3]

Case History

An 8-year-old boy, born of a nonconsanguineous marriage and with no family history of cancer, presented with a 2-month-old history of bulge in the frontal region of the scalp. It was initially peanut-sized, and showed subsequent increase in size. The swelling was associated with mild pain. Skin over the swelling, however, was normal. There were no constitutional symptoms, no loss of weight, or loss of appetite. On examination, the vitals were stable. There was no sinus at the site of the swelling. No neurological deficits were present.

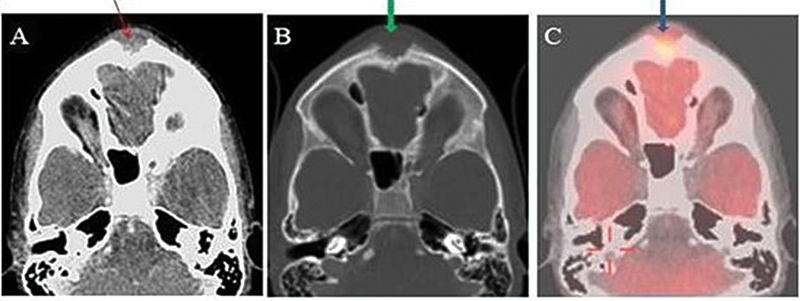

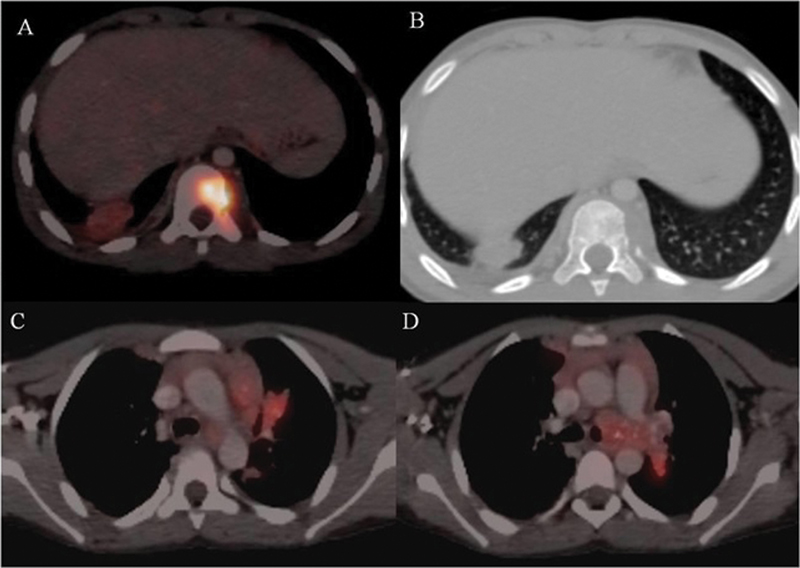

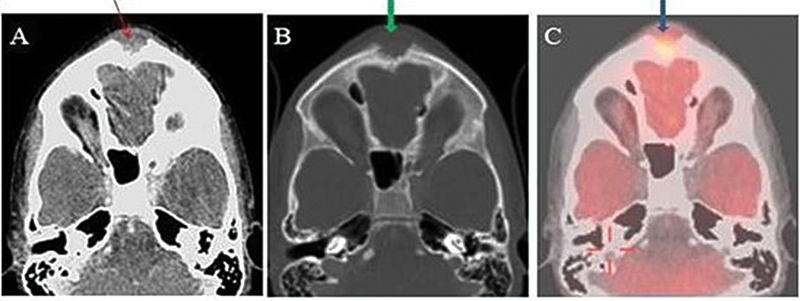

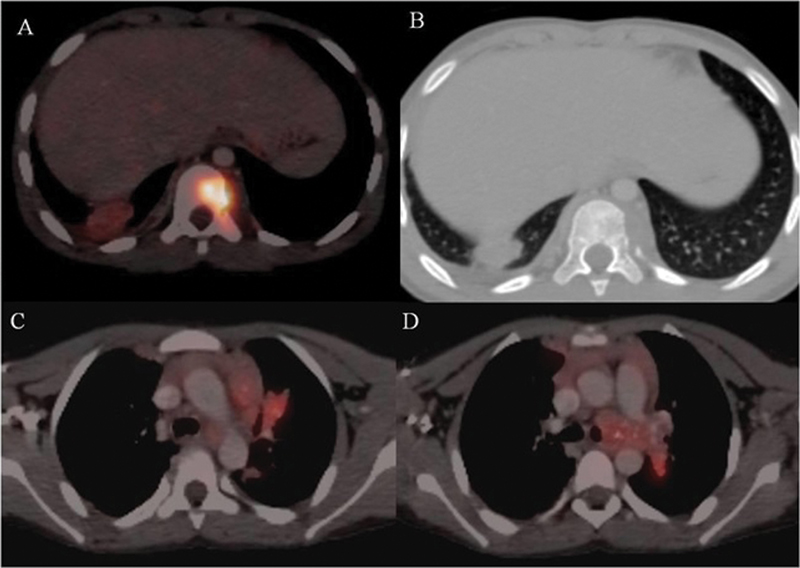

There was no pallor or organomegaly. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography was done outside our institute that revealed a hypermetabolic osteolytic lesion in the frontal bone in the midline as shown in [Fig. 1] and D10 vertebra body associated with soft tissue component. Pleural and parenchymal nodules with associated mediastinal lymph nodes (left hilar, left prevascular, aorta pulmonary, paratracheal, pretracheal and subcarinal nodes) were also seen as shown in [Fig. 2]. A frontal bone lesion biopsy was performed under ultrasonography guidance for further assessment, and the sample was tested for acid-fast bacilli staining and polymerase chain reaction (cartridge based nucleic-acid amplification) testing. Results revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of TB etiology. The patient took antitubercular drugs including rifampicin (10 mg/kg), ethambutol (15 mg/kg), isoniazid (5 mg/kg), and pyrazinamide (25 mg/kg) for a period of 3 months followed by rifampicin (10 mg/kg) and isoniazid (5mg/kg) for the next 9 months. The swelling size reduced and complete resolution of the scalp lesion was noted 3 months post initiating the therapy.

| Fig 1 : (A) Axial computed tomography (CT) soft tissue window shows a lytic lesion in the frontal bone with associated soft tissue (red arrow). (B) Axial CT bone window shows soft tissue in the frontal bone associated with erosion of underlying bone. No periosteal reaction was seen. (C) The fused transverse image shows 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose avid lytic frontal bone lesion. Possibilities on imaging were Langhans cell histiocytosis, metastasis. Frontal bone lesion biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of tuberculous etiology.

| Figure 2: (A, B) Axial positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) shows a lytic lesion with associated soft tissue involving body of D10 vertebrae. (C, D) Axial PET-CT shows pleura and parenchymal nodules with associated mediastinal lymph nodes with foci of calcification within.

Discussion

TB of the calvarium is almost always secondary to primary tubercular infection at various other sites such as lungs, lymph nodes, bones, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system. It is highly unusual to have isolated calvarial TB. There is a male preponderance, with the male to female ratio being 2:1. The maximum numbers of cases (75–80%) occur in less than 20 years of age.[3] It is extremely rare in infants, likely due to a paucity of cancellous bone. Due to the relatively higher proportion of cancellous bone, the frontal and parietal bones are most frequently damaged, followed by the occipital and sphenoid bones. Sphenoid bone involvement has been reported in a few cases.[4] The tubercular bacilli from the primary focus hematogenously seed the diploe to begin the pathogenesis of calvarial TB. The virulence depends on the patient's state of immunity. In immunodeficiency states, there is increased pathogenicity of the organism that causes the infection to spread to both the outer and inner table, thus destroying them, causing obliteration of capillaries, and replacement of bony trabeculae by granulation tissue. Microscopic examination shows necrotic areas, caseation, granulation tissue, epithelial cells, and Langhans giant cells. Involvement of the outer table leads to the formation of soft tissue swelling in the subgaleal region also referred to as Pott's puffy tumor and discharging sinuses. On the other hand, extradural granulation tissue forms when the inner table is involved and its extension continues. Since cranial sutures do not prevent granulation tissue from spreading, substantial bone destruction may take place before a sinus or swelling manifests. The majority of patients with frontal bone TB have painless scalp edema and discharge-producing sinuses. Initial presentation with seizures, focal neurological deficits, and meningeal signs is uncommon. Despite the dura being an effective barrier, subdural empyemas, meningitis, and intraparenchymal extension can also occur. Usually, skeletal TB occurs along with pulmonary involvement.[3] Sometimes, it may have local spread from adjacent mastoiditis. Trauma is also considered as one of the contributing factors due to increased vascularity and decreased resistance.[5] Radiological features are not always classical and diagnostic. The earliest finding is an area of rarefaction. This is followed by a punched-out lytic lesion with a central sequestrum. Sometimes, the defect may be surrounded by a sclerotic rim. There can be single or multiple lesions. Diffuse involvement or base of the skull is less commonly involved.[5] Since sometimes there may be multiple lytic lesions, multiple myeloma and metastases are considered differentials. Conventional radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used for the diagnosis of frontal bone TB. The disintegration of one or both of the tables is visible on CT with associated soft tissue swelling.[6] On conventional radiography, three types of tubercular osteitis lesions are identified based on the type of calvarial destruction. The most common subtype are small, punched-out lesions with granulation tissue covering the inner and outer tables of the calvaria also known as “circumscribed lytic lesions.” This term was used by Volkmann.[7] It is not associated with periosteal reaction.

Our case likely belonged to this subtype of tubercular osteitis, based on its radiological features as seen in [Fig. 1].

“Spreading-type” is the term coined for lesions causing extensive extradural granulation tissue in addition to substantial damage of the inner skull table. The least common is the “circumscribed sclerotic variant.”[8] Periosteal reaction is very rare but has been reported. CT is used to assess the degree of bone involvement, demonstration of the soft tissue component, sequestrum, and spread of disease to the extradural space meninges and brain parenchyma. A hypoattenuating lentiform or crescent-shaped collection describes the characteristic appearance of epidural granulation tissue on CT. The surrounding meninges show intense post-contrast enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT scan. MRI reveals a high signal intensity soft tissue mass within the bone defect projecting into the epidural space, with intense capsular enhancement on post-contrast sequences. MRI has higher sensitivity for the detection of meningeal enhancement, ventriculitis, and intraparenchymal granulomas or tuberculomas (rarely present along with calvarial TB). MRI was not required in our case as neurological symptoms suggestive of complications were absent.

Microbiological and histological confirmation is essential before starting Ziehl Neelsen staining. Biopsy in our case proved fruitful in clenching the diagnosis of TB as necrotizing granulomatous inflammation was detected on histopathological examination, which was further confirmed to be of tubercular etiology by Ziehl Neelsen staining and polymerase chain reaction testing. Other causes of necrotizing granulomas, which could be considered in cases of noninfective cases, include vasculitis such as Wegener's granulomatosis, rheumatoid nodules, and sarcoidosis.

Frontal bone or calvarial TB was primarily treated through surgery, before the advent of modern antitubercular therapy. Surgery is now reserved for patients with large epidural collections, extensive bone destruction, and sequestrum formation or in cases of mass effect on the brain or focal neurological deficits. The sinus tract is removed along with the complete excision of the damaged bone and debridement of the granulation tissue. However, the treatment of tubercular osteomyelitis of the skull is antitubercular treatment with appropriate antibiotic cover for secondary infections. Current guidelines advocate five drugs for at least 24 months. The important differentials to be considered in cases of TB of the frontal bone are pyogenic osteomyelitis; Langhans cell histiocytosis, multiple myeloma, epidermoid/dermoid cyst, and metastases. [Table 1] shows differential diagnosis of osteolytic calvarial lesions that can mimic calvarial TB.

|

Pathology |

Age |

Radiograph |

CT |

MRI |

PET |

Additional features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pyogenic osteomyelitis |

Any age; however, more common in children and adolescents |

ACUTE: Ill-defined lucent area with or without periosteal reaction, usually associated with sinusitis/mastoiditis CHRONIC: Osteolytic lesion with or without sequestrum and/or involucrum |

An osteolytic lesion with or without dead necrotic bone / new bone formation |

T1: Isointense to hypointense lesion Cortical destruction T2: Hyperintense lesion with surrounding high SI edema T1c + : Enhancement of periphery of associated collections and surrounding soft tissue |

Hypermetabolic |

Constitutional symptoms Raised WBC count Blood cultures are positive for bacterial/fungal organisms |

|

Langhan's cell histiocytosis |

Children |

Geographic skull: Single (eosinophilic granuloma) or multiple osteolytic lesions without sclerotic rim Button sequestrum |

An osteolytic lesion with a “bevelled edge” appearance (due to asymmetrical involvement of the inner and outer tables) (“hole within a hole” sign) Button sequestrum |

T1: Isointense to hypointense T2: Heterogeneously hyperintense T1c + : Marked enhancement |

Hypermetabolic |

Asymptomatic or constitutional symptoms may be present depending on multisystem involvement. Histopathology shows “Langhans cells” and immunohistochemistry is positive for CD1a and/or CD207 |

|

Multiple myeloma |

>40 years, With maximum cases between 50 and 70 years |

Raindrop skull: Multiple, variable-sized well-defined punched out osteolytic lesions without sclerotic rim |

Osteolytic lesions throughout the skull Axial and appendicular skeletal involvement in the form of diffuse osteopenia, osteolytic lesions with endosteal scalloping, and vertebral compression fractures |

T1: Hypointense T2: Hyperintense T1C + : Post-contrast enhancement seen |

Hypermetabolic |

Monoclonal gammopathy (IgA and/or IgG) Reversal of albumin/globulin ratio Bence Jones protein proteinuria Hypercalcemia |

|

Metastasis |

Depend on primary cancer, however more common in the older age group. Commonly from neuroblastomas and Ewing's sarcoma in children |

Commonly osteolytic, maybe be mixed/sclerotic depending upon the primary malignancy. May show spiculated (“hair-on-end”) periosteal reaction |

Commonly osteolytic, maybe be mixed/sclerotic. |

T1: Isointense to hypointense T2: Hyperintense T1C + : Post-contrast enhancement seen |

Hypermetabolic |

|

|

Dermoid/epidermoid cyst |

Any age, however common in 3rd to 4th decades |

Well-defined osteolytic lesion with lobulated margins and sclerotic rim |

Well-demarcated osteolytic lesion with smooth/lobulated margins, affecting the inner table more affected than the outer table. Internal fat density and/or calcification |

T1: Both cysts appear hyperintense T2: Varying signal depending on content T1C + : Dermoid cysts may show peripheral enhancement Intradiploic epidermoid cysts do not enhance |

Variable metabolic activity |

Dermoid cysts develop along the midline Painless swellings with or without associated sinus tract Epidermoid cysts show restricted diffusion on DWI |

References

- Ram H, Kumar S, Atam V, Kumar M. Primary tuberculosis of zygomatic bone: a rare case report. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2020; May 1; 13 (05) 815-817

- Strauss DC. Tuberculosis of the flat bones of the vault of the skull. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1933; 57: 384-398

- Meng CM, Wu YK. Tuberculosis of the flat bones of the vault of the skull: a study of forty cases. J Bone Jt Surg 1942; 24 (02) 341-353

- Thomas ML, Reid BR. Cranial tuberculosis presenting with proptosis. Radiology 1971; 100 (01) 91-92

- LeRoux PD, Griffin GE, Marsh HT, Winn HR. Tuberculosis of the skull–a rare condition: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1990; 26 (05) 851-855 , discussion 855–856

- Raut AA, Nagar AM, Muzumdar D. et al. Imaging features of calvarial tuberculosis: a study of 42 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25 (03) 409-414

- Volkmann R. Die perforierende Tuberkulose der Knochen des Schädeldaches. . [Perforating tuberculosis of the skull bones] Zentralbl Chir 1880; 7: 3-7

- Mohanty S, Rao CJ, Mukherjee KC. Tuberculosis of the skull. Int Surg 1981; 66 (01) 81-83

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

26 September 2023

© 2023. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Primary mandibular tuberculous osteomyelitis mimicking ameloblastoma: A case report and literature review of mandibular tuberculous osteomyelitisChandrashekhar Chalwade, Archives of Plastic Surgery

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Frontal Sinus Presenting as a Pott Puffy Tumor: Case ReportNickalus Khan, Journal of Neurological Surgery Reports, 2015

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Frontal Sinus Presenting as a Pott Puffy Tumor: Case ReportNickalus Khan, J Neurol Surg Rep, 2015

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Frontal Sinus Presenting as a Pott Puffy Tumor: Case ReportNickalus Khan, VCOT Open, 2015

- Concurrent Inverted Papilloma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Intradural Extension Presenting with Frontal Lobe SyndromeAbdul Jaleel, Indian Journal of Neurosurgery, 2021

- UML modeling and development of airborne warning radar detecting process<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Predicting Walking Ability Following Lower Limb Amputation: An Updated Systematic Literature Review<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Geophysical approaches to the exploration of lithium pegmatites and a case study in Koktohay<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- MFCA extension form a life cycle perspective: Mechanisms, methods and case study<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- The Tax Characterisation of 'Earn-Outs'<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

| Fig 1 : (A) Axial computed tomography (CT) soft tissue window shows a lytic lesion in the frontal bone with associated soft tissue (red arrow). (B) Axial CT bone window shows soft tissue in the frontal bone associated with erosion of underlying bone. No periosteal reaction was seen. (C) The fused transverse image shows 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose avid lytic frontal bone lesion. Possibilities on imaging were Langhans cell histiocytosis, metastasis. Frontal bone lesion biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of tuberculous etiology.

| Figure 2: (A, B) Axial positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) shows a lytic lesion with associated soft tissue involving body of D10 vertebrae. (C, D) Axial PET-CT shows pleura and parenchymal nodules with associated mediastinal lymph nodes with foci of calcification within.

References

- Ram H, Kumar S, Atam V, Kumar M. Primary tuberculosis of zygomatic bone: a rare case report. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2020; May 1; 13 (05) 815-817

- Strauss DC. Tuberculosis of the flat bones of the vault of the skull. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1933; 57: 384-398

- Meng CM, Wu YK. Tuberculosis of the flat bones of the vault of the skull: a study of forty cases. J Bone Jt Surg 1942; 24 (02) 341-353

- Thomas ML, Reid BR. Cranial tuberculosis presenting with proptosis. Radiology 1971; 100 (01) 91-92

- LeRoux PD, Griffin GE, Marsh HT, Winn HR. Tuberculosis of the skull–a rare condition: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1990; 26 (05) 851-855 , discussion 855–856

- Raut AA, Nagar AM, Muzumdar D. et al. Imaging features of calvarial tuberculosis: a study of 42 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25 (03) 409-414

- Volkmann R. Die perforierende Tuberkulose der Knochen des Schädeldaches. . [Perforating tuberculosis of the skull bones] Zentralbl Chir 1880; 7: 3-7

- Mohanty S, Rao CJ, Mukherjee KC. Tuberculosis of the skull. Int Surg 1981; 66 (01) 81-83

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share