When Less Is More: An Avenue for Academia–Industry Collaboration in Pediatric Cancer

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025; 46(03): 318-320

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0044-1800795

We read with interest the article by de Wilde et al that explores partnerships between academia and industry in conducting trials for pediatric cancer drug approval.[1] Cancers in the pediatric group have high cure rates and offer the possibility of significant gains in terms of years of life lived in the event of sustained remission. The pace of cancer drug development has traditionally been slower in children, with reported median lag periods of over 5 years for approvals in comparison to adult use.[2] Legislation mandating pediatric studies for drugs being tested in adults has helped accelerate this process over the last decade.[1] However, the global reach of such approvals is limited. Childhood cancer survival rates are reported to be as high as 80% in high-income countries (HICs), while low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lag behind.[1] [3] Treatment abandonment and social barriers to obtaining treatment are significant issues in LMICs, which may be further exacerbated by high costs of care.[4] Thus, drug approval is only an initial step in the process of translating drug development into survival benefits in childhood cancer. The role of academia–pharmaceutical collaborations in enhancing drug access remains unexplored.

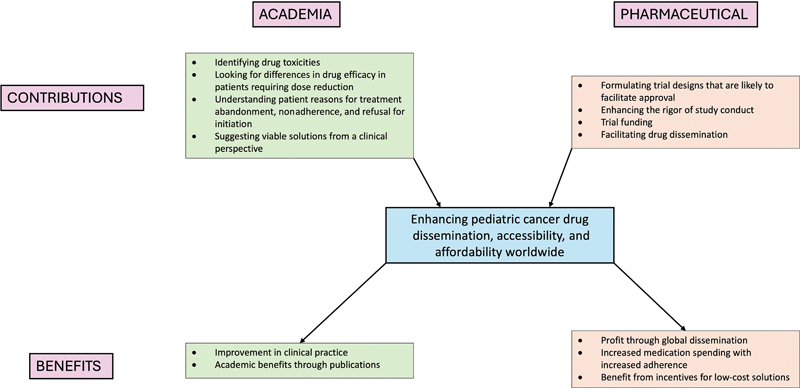

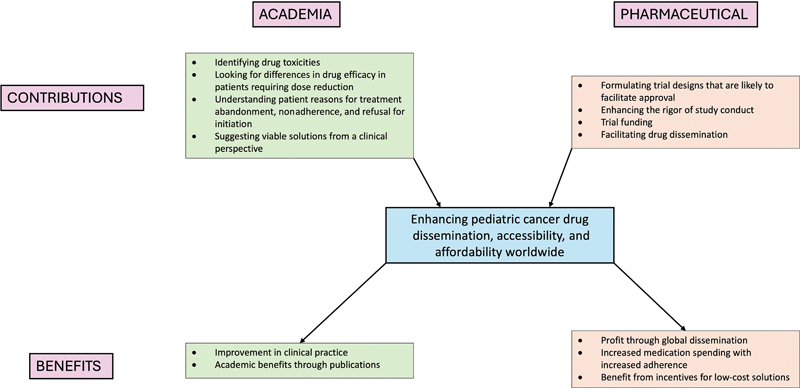

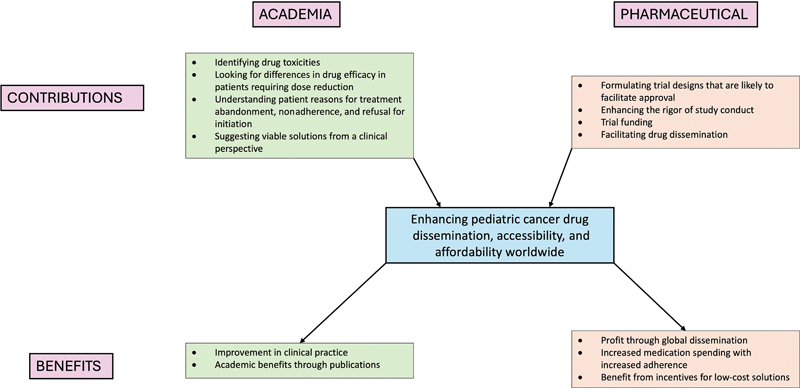

Traditionally, the degree of academic involvement in drug trials, as opposed to pharmaceutical company involvement, is higher in pediatric cancers than in adult cancers. The article by de Wilde et al has emphasized the vital role of partnerships between academia and industry in conducting trials for pediatric cancer drug approval.[1] Clinicians can access large hospital databases that provide real-world patient data about drug use patterns, efficacy, and toxicity. They also have more opportunities to understand the patient's perspective holistically regarding reasons for satisfaction with treatment, nonadherence, treatment refusal, and abandonment. Thus, they may be better placed to identify routine clinical problems and design patient-friendly and cost-effective solutions. On the other hand, pharmaceutical companies could provide funding and rigor to trial conduct and may be better equipped to steer trial protocols in a direction that facilitates approval. In India and other LMICs, drug trials are predominantly pharmaceutical driven.[5] The lack of academic involvement in clinical trials may be due to financial, technical, and regulatory constraints. It has been seen that randomized trials of cancer drugs conducted in LMICs are more likely to identify larger effect sizes and identify effective therapies in comparison to those in HICs.[6] Thus, collaborative ventures in LMICs are likely to reap rewards for both academicians and clinicians. [Fig. 1] shows how such collaborations may enable better drug access and benefit the partners involved.

| Fig 1 : Academia–drug manufacturer partnerships for enhancing cancer drug access: the contributions of and benefits to each partner.

Tannock et al found in their review that drug doses used in adult clinical trials of new drugs are often higher than the effective doses identified in earlier phases.[7] Many investigator-initiated trials have explored the efficacy of lower doses of approved drugs ([Table 1]).[8] [9] [10] [11] [12] While some of these trials may have been conducted with the aim of reducing drug-related toxicities with the support of government funding sources, they have the collateral benefit of reducing treatment-related costs and health care resource utilization.[10] In general, cost-reduction strategies are perceived as not being in line with the commercial interests of pharmaceutical companies. However, a few pharmaceutical-funded trials have also attempted to seek out pharmacoeconomic strategies. A pharmaceutical-funded phase III study of low-dose nivolumab in India demonstrated significant improvement in advanced head and neck carcinoma outcomes.[8] This critical finding has opened up the possibility of expanding the use of immunotherapy for cancer patients in resource-challenged settings.

|

Sl. no. |

Drug |

Study |

Trial description |

Funding agency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Targeted therapeutics |

||||

|

1 |

Ibrutinib |

Chen et al[10] |

Pilot study of ibrutinib dose reduction in chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

Government |

|

2 |

Trastuzumab |

Earl et al[9] |

Phase III trial 6 vs. 12 mo of adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer |

Government |

|

Immunotherapy |

||||

|

1 |

Nivolumab |

Patil et al[8] |

Phase III randomized study evaluating the addition of low-dose nivolumab to palliative chemotherapy in head and neck carcinoma |

Pharmaceutical company |

|

Supportive care drugs |

||||

|

1 |

Rasburicase |

Vadhan-Raj et al[11] |

Trial of single-dose rasburicase vs. daily dosing for 5 d in adult patients at risk of tumor lysis syndrome |

Pharmaceutical company |

|

2 |

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

Clemons et al[12] |

Trial comparing 5- vs. 7- vs. 10-d schedules of filgrastim for primary prophylaxis of febrile neutropenia in early-stage breast cancer patients |

Academic collaboration |

We read with interest the article by de Wilde et al that explores partnerships between academia and industry in conducting trials for pediatric cancer drug approval.[1] Cancers in the pediatric group have high cure rates and offer the possibility of significant gains in terms of years of life lived in the event of sustained remission. The pace of cancer drug development has traditionally been slower in children, with reported median lag periods of over 5 years for approvals in comparison to adult use.[2] Legislation mandating pediatric studies for drugs being tested in adults has helped accelerate this process over the last decade.[1] However, the global reach of such approvals is limited. Childhood cancer survival rates are reported to be as high as 80%-in high-income countries (HICs), while low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lag behind.[1] [3] Treatment abandonment and social barriers to obtaining treatment are significant issues in LMICs, which may be further exacerbated by high costs of care.[4] Thus, drug approval is only an initial step in the process of translating drug development into survival benefits in childhood cancer. The role of academia–pharmaceutical collaborations in enhancing drug access remains unexplored.

Traditionally, the degree of academic involvement in drug trials, as opposed to pharmaceutical company involvement, is higher in pediatric cancers than in adult cancers. The article by de Wilde et al has emphasized the vital role of partnerships between academia and industry in conducting trials for pediatric cancer drug approval.[1] Clinicians can access large hospital databases that provide real-world patient data about drug use patterns, efficacy, and toxicity. They also have more opportunities to understand the patient's perspective holistically regarding reasons for satisfaction with treatment, nonadherence, treatment refusal, and abandonment. Thus, they may be better placed to identify routine clinical problems and design patient-friendly and cost-effective solutions. On the other hand, pharmaceutical companies could provide funding and rigor to trial conduct and may be better equipped to steer trial protocols in a direction that facilitates approval. In India and other LMICs, drug trials are predominantly pharmaceutical driven.[5] The lack of academic involvement in clinical trials may be due to financial, technical, and regulatory constraints. It has been seen that randomized trials of cancer drugs conducted in LMICs are more likely to identify larger effect sizes and identify effective therapies in comparison to those in HICs.[6] Thus, collaborative ventures in LMICs are likely to reap rewards for both academicians and clinicians. [Fig. 1] shows how such collaborations may enable better drug access and benefit the partners involved.

| Fig 1 : Academia–drug manufacturer partnerships for enhancing cancer drug access: the contributions of and benefits to each partner.

Tannock et al found in their review that drug doses used in adult clinical trials of new drugs are often higher than the effective doses identified in earlier phases.[7] Many investigator-initiated trials have explored the efficacy of lower doses of approved drugs ([Table 1]).[8] [9] [10] [11] [12] While some of these trials may have been conducted with the aim of reducing drug-related toxicities with the support of government funding sources, they have the collateral benefit of reducing treatment-related costs and health care resource utilization.[10] In general, cost-reduction strategies are perceived as not being in line with the commercial interests of pharmaceutical companies. However, a few pharmaceutical-funded trials have also attempted to seek out pharmacoeconomic strategies. A pharmaceutical-funded phase III study of low-dose nivolumab in India demonstrated significant improvement in advanced head and neck carcinoma outcomes.[8] This critical finding has opened up the possibility of expanding the use of immunotherapy for cancer patients in resource-challenged settings

|

Sl. no. |

Drug |

Study |

Trial description |

Funding agency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Targeted therapeutics |

||||

|

1 |

Ibrutinib |

Chen et al[10] |

Pilot study of ibrutinib dose reduction in chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

Government |

|

2 |

Trastuzumab |

Earl et al[9] |

Phase III trial 6 vs. 12 mo of adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer |

Government |

|

Immunotherapy |

||||

|

1 |

Nivolumab |

Patil et al[8] |

Phase III randomized study evaluating the addition of low-dose nivolumab to palliative chemotherapy in head and neck carcinoma |

Pharmaceutical company |

|

Supportive care drugs |

||||

|

1 |

Rasburicase |

Vadhan-Raj et al[11] |

Trial of single-dose rasburicase vs. daily dosing for 5 d in adult patients at risk of tumor lysis syndrome |

Pharmaceutical company |

|

2 |

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

Clemons et al[12] |

Trial comparing 5- vs. 7- vs. 10-d schedules of filgrastim for primary prophylaxis of febrile neutropenia in early-stage breast cancer patients |

Academic collaboration |

References

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

10 February 2025

© 2025. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Surgery for Otitis Media with Effusion: A Survey of Otolaryngologists Who Treat Children in BrazilManoel de Nobrega, International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology

- Management of Pediatric and Adolescent Breast MassesRaelene D. Kennedy, Seminars in Plastic Surgery, 2013

- Management of Pediatric and Adolescent Breast MassesRaelene D. Kennedy, Semin Plast Surg, 2013

- Academic exchange in the COVID-19 eraArchives of Plastic Surgery, 2020

- Evaluation of Organisational Structures of Self-help Groups in the Field of Paediatric OrthopaedicsChristian-Dominik Peterlein, Zentralblatt für Chirurgie - Zeitschrift für Allgemeine, Viszeral-, Thorax- und Gefäßchirurgie, 2018

- A case for establishment of the Ferrous Materials Development Network (FMDN) in South Africa<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- A Vague Set Based OWA Method for Talent Evaluation<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Review of thermal conductivity in epoxy thermosets and composites: Mechanisms, parameters, and filler influences<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Robotic-assisted automated in situ bioprinting<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Cross-border issues and technology and management solutions during COVID-19<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

| Fig 1 : Academia–drug manufacturer partnerships for enhancing cancer drug access: the contributions of and benefits to each partner.

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share