Investigating Diagnostic and Treatment Barriers in Cancer Care: A Rural Perspective from Western Maharashtra, India

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025; 46(04): 397-408

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0045-1804891

Abstract

Introduction Noncommunicable diseases, particularly cancer, are increasingly burdening India's health care system. Despite the implementation of various national cancer control programs, notable barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment persist, especially in rural regions.

Objectives This study aims to identify these barriers and assess diagnostic and treatment intervals among cancer patients in rural Western Maharashtra.

Materials and Methods A cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary cancer hospital from January to March 2024. Histopathologically confirmed patients with cancer (aged ≥ 18 years) who attended the radiotherapy and chemotherapy outpatient departments for treatment were included. Data was collected using structured interviews, focusing on sociodemographic factors, diagnostic intervals (from first symptom to final diagnosis), and treatment intervals (from final diagnosis to treatment initiation). Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc software.

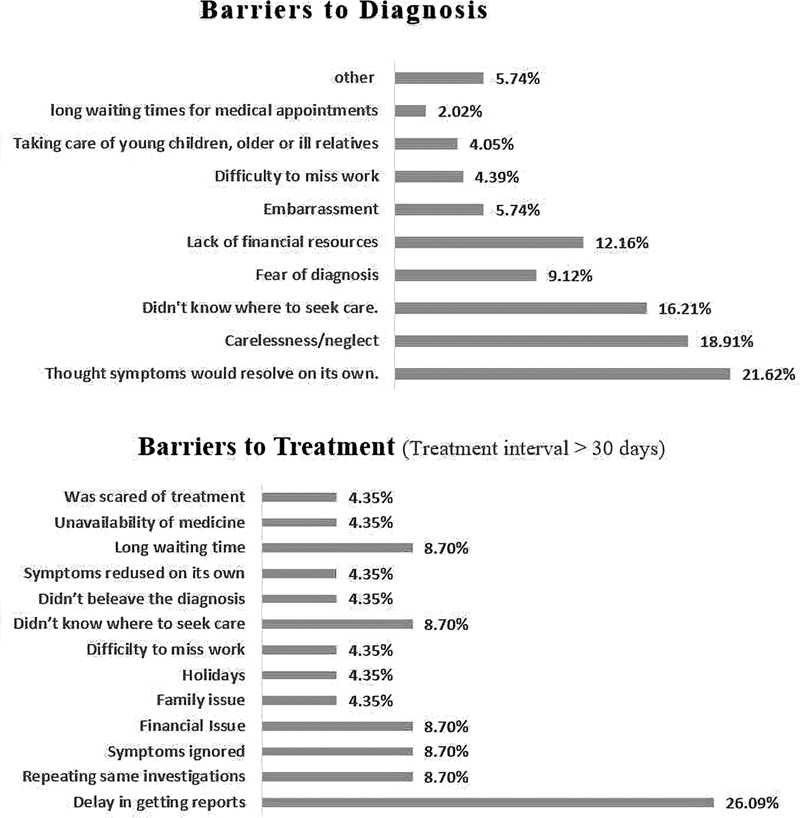

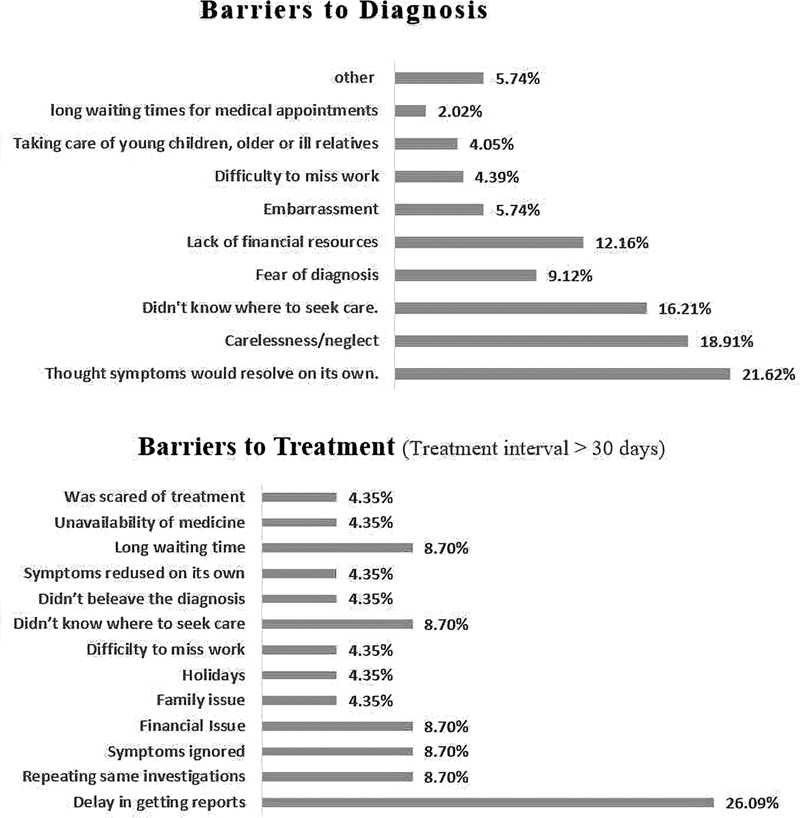

Results Out of 127 patients analyzed, the mean age was 53.4 years, with 68.5%. being female. The majority resided in rural areas (52.0%). Breast cancer (26.8%), lip and oral cavity cancer (15.0%), and cervical cancer (10.2%) were the most prevalent among patients. The median total interval in diagnosis was 86 days, with a median diagnostic interval of 61 days and a median treatment interval of 8 days. Substantial barriers to timely diagnosis included misconceptions about symptom severity, neglect, and lack of knowledge about where to seek care. Rural residency and diagnosis of the first doctor consulted were significantly associated with longer diagnostic intervals.

Conclusion The study identified critical barriers to timely cancer diagnosis and treatment in rural Western Maharashtra, highlighting the need for increased awareness, better access to health care, and streamlined diagnostic processes. Addressing these challenges through targeted strategies can potentially reduce delays and improve cancer care outcomes, enhancing survival rates and quality of life for patients in this region. This study highlights the urgency for health care policymakers to prioritize and address these barriers to improve cancer care in rural India.

Authors' Contributions

1. A.N.:

- Concept: Contributed to the initial idea and framework of the study.

- Design: Helped design the study methodology.

- Intellectual Content: Provided key insights and intellectual content throughout the study.

- Literature Search: Conducted a comprehensive literature review to support the study's background and rationale.

- Clinical Studies: Coordinated and supervised the data collection for the study.

- Data Analysis: Participated in the interpretation of the data.

- Statistical Analysis: Assisted in performing the statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed significantly to the writing of the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed and approved the final manuscript before submission.

2. K.V.:

- Concept: Contributed to the development of the study concept.

- Design: Assisted in the design of the study methodology.

- Literature Search: Assisted with the literature review.

- Data Acquisition: Collected data from clinical sources.

- Data Analysis: Assisted in data interpretation.

- Statistical Analysis: Helped with statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Assisted in writing the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Helped with manuscript revisions.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed the manuscript draft.

3. G.R.N.:

- Concept: Provided input on the study concept.

- Design: Assisted with study design.

- Intellectual Content: Contributed to the intellectual content of the study.

- Literature Search: Participated in the literature search.

- Clinical Studies: Involved in clinical data collection.

- Data Acquisition: Contributed to data collection efforts.

- Statistical Analysis: Participated in the statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed to drafting the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Assisted with manuscript editing.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript.

4. S.R.:

- Concept: Helped refine the study concept.

- Design: Contributed to the study design.

- Literature Search: Assisted in gathering relevant literature.

- Data Acquisition: Assisted in data acquisition.

- Data Analysis: Helped analyze the data.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed to manuscript writing.

- Manuscript Editing: Assisted with revisions.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed the manuscript.

5. A.R.:

- Concept: Contributed to the conceptual framework.

- Design: Assisted in designing the study.

- Literature Search: Helped with the literature review.

- Data Acquisition: Participated in data collection.

- Data Analysis: Assisted in interpreting the data.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed to drafting sections of the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Helped edit the manuscript.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed the manuscript draft.

6. D.M.:

- Concept: Provided input on the initial concept.

- Design: Assisted in the study design.

- Literature Search: Participated in the literature search.

- Data Acquisition: Assisted in gathering data.

- Statistical Analysis: Contributed to the statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Helped write the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Assisted with editing the manuscript.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed and approved the final draft.

Patient Consent

Patient consent is not required.

Publication History

Article published online:

24 February 2025

© 2025. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Study of socio‑demographic determinants of esophageal cancer at a tertiary care teaching hospital of Western Maharashtra, IndiaPurushottam A. Giri, South Asian Journal of Cancer, 2014

- In response to “Telemedicine: An Era Yet to Flourish in India”Neeraj Kumar, Annals of the National Academy of Medical Sciences (India)

- In response to “Telemedicine: An Era Yet to Flourish in India”Neeraj Kumar, VCOT Open

- Quality of Life of Primary Caregivers Attending a Rural Cancer Centre in Western Maharashtra: A Cross-Sectional StudyShubham S. Kulkarni, Indian J Radiol Imaging, 2021

- Financial Burden Faced by Families due to Out‑of‑pocket Expenses during the Treatment of their Cancer Children: An Indian PerspectiveLatha M Sneha, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2017

- Cancer in the elderly in India: Challenges, attitudes, and strategies for improvementAnmol Mahani, Annals of Geriatric Education and Medical Sciences, 2025

- Evaluation of spectrum of cervical lesions by PAP smear in rural medical college<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> Deepu Mathew Cherian, IP Journal of Diagnostic Pathology and Oncology, 2019 - Profile of deaths due to burn injuries: A retrospective study of eight years in a tertiary care centre in Western MaharashtraRashid Nehal Khan, IP International Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicological Sciences, 2020

- A descriptive study to assess the drug sensitivity pattern to antitubercular drugs in patients visiting department of respiratory medicine at a tertiary care ho...<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> HS Sndhu, The Journal of Community Health Management, 2020 - Advancing Cervical Cancer Prevention in India: Implementation Science PrioritiesSuneeta Krishnan, The Oncologist, 2013

Abstract

Introduction Noncommunicable diseases, particularly cancer, are increasingly burdening India's health care system. Despite the implementation of various national cancer control programs, notable barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment persist, especially in rural regions.

Objectives This study aims to identify these barriers and assess diagnostic and treatment intervals among cancer patients in rural Western Maharashtra.

Materials and Methods A cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary cancer hospital from January to March 2024. Histopathologically confirmed patients with cancer (aged ≥ 18 years) who attended the radiotherapy and chemotherapy outpatient departments for treatment were included. Data was collected using structured interviews, focusing on sociodemographic factors, diagnostic intervals (from first symptom to final diagnosis), and treatment intervals (from final diagnosis to treatment initiation). Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc software.

Results Out of 127 patients analyzed, the mean age was 53.4 years, with 68.5%. being female. The majority resided in rural areas (52.0%). Breast cancer (26.8%), lip and oral cavity cancer (15.0%), and cervical cancer (10.2%) were the most prevalent among patients. The median total interval in diagnosis was 86 days, with a median diagnostic interval of 61 days and a median treatment interval of 8 days. Substantial barriers to timely diagnosis included misconceptions about symptom severity, neglect, and lack of knowledge about where to seek care. Rural residency and diagnosis of the first doctor consulted were significantly associated with longer diagnostic intervals.

Conclusion The study identified critical barriers to timely cancer diagnosis and treatment in rural Western Maharashtra, highlighting the need for increased awareness, better access to health care, and streamlined diagnostic processes. Addressing these challenges through targeted strategies can potentially reduce delays and improve cancer care outcomes, enhancing survival rates and quality of life for patients in this region. This study highlights the urgency for health care policymakers to prioritize and address these barriers to improve cancer care in rural India.

Keywords

barriers - cancer - diagnostic interval - noncommunicable diseases - treatment intervalIntroduction

Globally, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) account for 74%. of all deaths (∼41 million), with cancer being a leading cause, resulting in 9.3 million deaths.[1] In India, the burden of NCDs, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus, is rising rapidly and surpassing that of communicable diseases like tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection . In India, NCDs are expected to cause around 60% of overall deaths and result in a considerable loss of productive years of life. Premature deaths from NCDs, including cancer, are expected to increase over time.[2]

According to a recent report by the World Health Organization (WHO), in countries with a high Human Development Index (HDI), every 12th woman will be diagnosed with breast cancer, and 1 in 71 diagnosed women will succumb to it. Conversely, in low-HDI countries such as India, only 1 out of every 27th women will be diagnosed with carcinoma of the breast, but every 48th woman will die from it, primarily due to late diagnosis and restricted access to treatment options.[3] Additionally, a recent report by the National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research highlights a worrying decline in overall health and a sharp increase in cancer and other NCDs in India.

The report calls attention to a growing “silent epidemic” that demands urgent action, projecting cancer cases in India to escalate from 1.39 million in 2020 to 1.57 million by 2025, exceeding global growth rates.[4]

To tackle the issue, the National Cancer Control Program (NCCP) was initiated in 1975 and revised in 1984 to 1985 with an emphasis on primary prevention and early cancer detection.[5] Acknowledging the common risk factors between cancer and other NCDs, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India merged the NCCP with the NCD Program in 2008, resulting in the National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke (NPCDCS).[2]

The Tertiary Care Cancer Centres (TCCC) scheme—part of the National Program for Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NP-NCD; formerly known as NPCDCS)—aims to establish or improve 20 state cancer institutes and 50 TCCCs to provide comprehensive cancer care. Guidelines have been issued for early detection of common cancers (oral, cervical, and breast) through population-based screening by frontline health care workers within the primary health care system.

In 2015, member states of the United Nations embraced the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, encompassing 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 3 strives to guarantee healthy lives and enhance well-being across all age groups by diminishing the occurrence of debilitating illnesses. One of its cancer-related objectives is diminishing premature mortality by one-third from NCDs through prevention, treatment, and the advancement of mental health and well-being.

Additionally, it aims to achieve universal health coverage, ensuring access to quality health care services and affordable essential medicines and vaccines.[6]

The Innovative Partnership for Action Against Cancer survey examined common cancers in Europe, such as skin, prostate, breast, and oral cancers, identifying some common barriers including lack of evidence, cancer stigma, and poorly organized patient pathways.

Other notable barriers are unequal access to primary care, affordability issues, travel difficulties, and unavailability of services in certain areas—underscoring the need for better information on the benefits of early detection.[7]

India is encountering a substantial oncology predicament as the increasing prevalence of cancer is highly burdening the health care system. This challenge is complex, encompassing issues such as insufficient infrastructure, restricted availability of high-quality care, and elevated treatment expenses.

As only a few studies have been performed regarding the barriers in diagnosis and treatment of cancer, it was proposed to take up this study in rural Western Maharashtra to identify the barriers which affect the patient's diagnosis and treatment of cancer. This study will also assess the time taken between the first symptom and final diagnosis of cancers by health care facilities/practitioners (diagnostic interval), the time taken between final diagnosis and initiation of treatment of cancers (treatment interval), and provide recommendations based on the study findings.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2024 to March 2024, at a tertiary cancer hospital located in a rural part of Western Maharashtra, India. The study encompassed a comprehensive examination of patients aged 18 years and older who were visiting the radiotherapy and chemotherapy outpatient departments of the hospital for treatment.

Eligibility Criteria

Our research focused on all patients of cancer visiting the tertiary cancer hospital, belonging to any gender, aged 18 years or above, and giving consent for study participation. Patients or caregivers unwilling to give consent, patients with diagnosed mental illness, and pregnant females were excluded from the study.

Sample Size

The study conducted by Gulzar et al[8] revealed that “financial issues” accounted for 81%. of delayed breast cancer presentations among patients. Entering this data into Win-Pepi software version 11.65, with an allowable error of 7.5%. and a 95%. confidence level, the calculated sample size was calculated to be as 106. Considering a nonresponse rate of 5%, the total sample size was calculated to be 111. However, in our study, we managed to include 130 patients.

Data Collection and Variables

We selected all confirmed cases of cancer, meeting our inclusion criteria. Interviews were performed with either patients or their caregivers using a pretested structured questionnaire, which was developed after an extensive literature review and piloted with 10%. of the sample population. The questionnaire focused on the timeframe of symptoms, days to final diagnosis, and any further delays. Specific inquiries were made to ascertain the diagnostic interval (the number of days between the first symptom and the final diagnosis) and treatment interval (the number of days between the final diagnosis and the initiation of treatment). Patients who reported a perceived delay in diagnosis were further queried to identify the reasons (barriers) for their delay, as were those who experienced a treatment delay exceeding 30 days. Additionally, patients' sociodemographic factors were assessed. To ensure the questionnaire's comprehensibility among the target population, it was translated into local language, Marathi. Permission was obtained from the head of the institution to conduct the study, and ethical clearance from the institute's ethics committee was secured before its commencement.

Primary and Secondary Outcome

The primary objective of the study was to identify the barriers affecting patients' diagnosis and treatment of cancer. The secondary objective was to evaluate the time elapsed between the first symptom and the final diagnosis of cancer by health care facilities or practitioners, and to identify any subsequent delays in initiating treatment.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included all patients with cancer, aged 18 years or above, regardless of gender, caste, or religion. However, patients with diagnosed mental illness, patients or caregivers unwilling to provide consent, and all pregnant females were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

After reviewing, the gathered data was entered into MedCalc software version 18.2.1 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Belgium). To determine statistical significance, the variables were coded, the confidence interval was set at 95%, and a p-value of < 0.05 was established. Descriptive analysis of the study variables was noted in percentages and means. To assess significant correlations between variables, chi-square and Mann–Whitney tests were applied where deemed applicable.

Ethical Approval

Before the study began, ethical clearance was obtained from the institute ethical committee. Permission was also secured from the institutional review board of Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Pune, Maharashtra, India, with approval number IESC/PGS/2022/209.

Survey responses were collected anonymously following the ethical guidelines as per the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring participant confidentiality through a system of codes and numbers. Participants were fully informed about the study's objectives and data collection methods to ensure transparency. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient or their caregiver before the study commenced.

Results

|

Age |

Mean |

SD |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall (N = 127) |

53.4 |

11.7 |

18 |

78 |

|

Female (N = 87) |

51.5 |

10.9 |

18 |

76 |

|

Male (N = 40) |

57.6 |

12.3 |

23 |

78 |

|

Distance from hospital |

Median |

IQR |

||

|

30 km |

16.5–106 |

1 km |

500 km |

|

|

Variable |

Counts |

% of total |

||

|

1. Religion |

||||

|

• Hindu |

119 |

93.7 |

||

|

• Jain |

1 |

0.8 |

||

|

• Muslim |

7 |

5.5 |

||

|

2. Sex |

||||

|

• Female |

87 |

68.5 |

||

|

• Male |

40 |

31.5 |

||

|

3. Place |

||||

|

• Rural |

66 |

52.0 |

||

|

• Urban |

61 |

48.0 |

||

|

4. Occupation |

||||

|

• Homemaker |

57 |

44.9 |

||

|

• Nongovernment employee |

9 |

7.1 |

||

|

• Retired |

8 |

6.3 |

||

|

• Self-employed |

43 |

33.9 |

||

|

• Unemployed |

8 |

6.3 |

||

|

• Government employee |

2 |

1.6 |

||

|

5. Education status |

||||

|

• No formal schooling |

37 |

29.1 |

||

|

• Less than primary school (< 1st> |

8 |

6.3 |

||

|

• Primary school (1–5th) |

24 |

18.9 |

||

|

• Secondary school (6–10th) |

22 |

17.3 |

||

|

• High school (11th-12th) |

21 |

16.5 |

||

|

• College/University |

7 |

5.5 |

||

|

• Postgraduation degree |

5 |

3.9 |

||

|

• Unknown |

3 |

2.4 |

||

|

6. Family history of cancer |

||||

|

• No |

110 |

86.6 |

||

|

• Yes |

17 |

13.4 |

||

|

7. Diabetes mellitus |

||||

|

• No |

113 |

89.0 |

||

|

• Yes |

14 |

11.0 |

||

|

8. Diet |

||||

|

• Nonveg |

82 |

64.6 |

||

|

• Veg |

45 |

35.4 |

||

|

9. Any addiction |

||||

|

• Yes |

57 |

44.88 |

||

|

• No |

70 |

55.12 |

||

|

10. Visit to GP prior to specialist |

||||

|

• No |

19 |

15.0 |

||

|

• Yes |

108 |

85.0 |

||

|

11. Means of problem identification |

||||

|

• Routine checkup |

34 |

26.8 |

||

|

• Screening |

3 |

2.4 |

||

|

• Self-discovery |

90 |

70.9 |

||

|

12. Patient's initial interpretation of symptoms |

||||

|

• Initial interpretation of cancer |

10 |

7.9 |

||

|

• Symptoms ignored |

48 |

37.8 |

||

|

• Initial worry |

69 |

54.3 |

||

|

13. Patient's reason for seeking medical care |

||||

|

• Appearance of symptoms |

38 |

29.9 |

||

|

• Persistence of symptoms |

24 |

18.9 |

||

|

• Worsening of symptoms |

65 |

51.2 |

||

|

14. Use of alternative medicine |

||||

|

• Ayurveda |

11 |

8.7 |

||

|

• Homeopathy |

6 |

4.7 |

||

|

• None |

110 |

86.6 |

||

|

15. Was there a delay in diagnosis (patient's perception) |

||||

|

• No |

34 |

26.8 |

||

|

• Yes |

93 |

73.2 |

||

|

16. First health service utilized |

||||

|

• Private |

109 |

85.8 |

||

|

• Public |

18 |

14.2 |

||

|

17. Number of different health services consulted before final diagnosis |

||||

|

• 0–1 |

31 |

24.4 |

||

|

• 2–3 |

80 |

63 |

||

|

• 4–5 |

12 |

9.4 |

||

|

• 6–7 |

4 |

3.2 |

||

|

18. Biopsy done before arrival to oncologist/cancer hospital |

||||

|

• No |

41 |

32.3 |

||

|

• Yes |

86 |

67.7 |

||

|

19. Diagnosis of the first doctor consulted |

||||

|

• Correctly diagnosed |

57 |

44.9 |

||

|

• Misdiagnosed |

49 |

38.6 |

||

|

• No diagnosis |

21 |

16.5 |

||

|

20. Has heard about screening |

||||

|

• No |

121 |

95.3 |

||

|

• Yes |

6 |

4.7 |

||

|

21. Knowledge about cancer |

||||

|

• No knowledge |

101 |

79.5 |

||

|

• Some knowledge |

26 |

20.5 |

||

|

22. Knowledge of the recommended age for first screening modality |

||||

|

• No |

125 |

98.4 |

||

|

• Yes |

2 |

1.6 |

||

|

23. Underwent chemo/radiotherapy |

||||

|

• No |

6 |

4.7 |

||

|

• Yes |

121 |

95.3 |

||

|

24. Did you choose to discontinue chemotherapy or radiotherapy at any point in time? |

||||

|

• No |

102 |

84.2 |

||

|

• Yes |

19 |

15.7 |

||

Fig 1: Barriers to diagnosis and treatment.

The most prevalent cancer types observed in the study were breast cancer (26.8%), followed by cancer of the lip and oral cavity (15.0%) and cervical cancer (10.2%) ([Table 2]). The most common cancers among men were cancer of the lip and oral cavity (35%), cancer of the rectum (15%), and cancer of the lung (10%), while in women carcinoma of breast (39.08%), cervix (14.90%), and ovary (13.70%) were the most common.

|

Diagnosis |

Counts (%) |

Common first symptoms |

|---|---|---|

|

Ca breast |

34 (26.8) |

• Lump in breast • Fullness in breast |

|

• Pain in breast |

||

|

Ca lip and oral cavity |

19 (15.0) |

• Ulcer on tongue • White patch on tongue • Tooth ache |

|

Ca cervix |

13 (10.2) |

• White discharge PV (per vagina) • Bleeding PV • Pain abdomen |

|

Ca ovary |

12 (9.5) |

• Pain abdomen • Abdominal distension • Anorexia, abdominal pain |

|

Ca rectum |

8 (6.3) |

• Pain in defecation • Bleeding per anus • Blood in stool |

|

Ca lung |

7 (5.5) |

|

|

Ca throat |

5 (3.9) |

|

|

Ca endometrium |

3 (2.4) |

|

|

Ca colon |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Ca esophagus |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Ca gallbladder |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Ca prostate |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Ca urinary bladder |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Ca vulva |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Cholangiocarcinoma |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Others |

12 (9.6) |

The median total interval in diagnosis was found to be 86 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 38–222). The median diagnostic interval was 61 days (IQR: 31–198), while the median treatment interval was 8 days (IQR: 3–20) ([Table 3]).

|

Diagnostic interval (d) |

Treatment interval (d) |

Total interval (d) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

N |

127 |

127 |

127 |

|

Median |

61 |

8 |

86 |

|

IQR |

31–198 |

3–20 |

38–222 |

|

Minimum |

7 |

1 |

12 |

|

Maximum |

3,134 |

545 |

3,148 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Note: Cancers with only a single case were excluded from this analysis.

Patients who initially sought care from private health services were associated with a median diagnostic interval of 61 days, compared with 91.5 days for those who utilized public services (p = 0.67). Patients who visited a general practitioner (GP) before seeing a specialist had shorter total intervals compared with those who did not (median: 76 vs. 117 days, p = 0.30) ([Table 5]). Moreover, the diagnosis of the first doctor consulted showed a significant association with diagnostic interval. There was also a significant trend toward longer diagnostic intervals with an increasing number of different health services utilized before the final diagnosis (p = 0.0361). Patients who initially interpreted their symptoms as indicative of cancer experienced shorter diagnostic intervals compared with those who ignored symptoms or expressed initial worry (p = 0.0003). Similarly, patients who sought medical care due to the worsening of symptoms had longer delay compared with those seeking care for the appearance or persistence of symptoms (p = 0.0052) ([Table 5]).

|

Variables |

Median interval |

IQR |

p-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnostic interval |

Rural |

106.5 |

31.00–214.00 |

|

|

0.026 |

||||

|

Urban |

31.0 |

30.00–122.25 |

||

|

Male |

31.0 |

30.00–234.50 |

||

|

0.37 |

||||

|

Female |

91.0 |

31.00–153.00 |

||

|

Addiction - Yes |

76.5 |

31.00–243.00 |

||

|

0.25 |

||||

|

Addiction – No |

36.0 |

31.00–153.00 |

||

|

No knowledge about cancer |

61.0 |

31.00–160.75 |

||

|

0.59 |

||||

|

Some knowledge about cancer |

31.0 |

30.00–258.00 |

||

|

First health service used - Private. |

61.0 |

31.00–153.00 |

||

|

0.67 |

||||

|

First health service used – Public |

91.5 |

30.00–334.00 |

||

|

Alternate medicine service used – Yes[a] |

153.0 |

29.25–372.75 |

||

|

0.58 |

||||

|

Alternate medicine service used – No |

61.0 |

31.00–153.00 |

||

|

Total Interval |

Visit to GP prior to a specialist – Yes |

76.0 |

37.00–205.00 |

|

|

0.30 |

||||

|

Visit to GP prior to a specialist – No |

117.0 |

47.500–323.25 |

||

|

Biopsy done prior to arrival to specialist/cancer hospital – Yes No |

74.5 |

37.00–163.00 |

0.14 |

|

|

100.0 |

43.50–423.50 |

|||

|

Diagnostic interval |

Patient's initial interpretation of symptoms ( n = 127) |

|||

|

Initial interpretation of cancer ( N ) |

Symptoms ignored ( N ) |

Initial worry ( N ) |

||

|

≤ 60 d |

8 |

12 |

39 |

0.0003 |

|

> 60 d |

2 |

36 |

30 |

|

|

Patient's reason for seeking medical care |

||||

|

Appearance of symptoms ( N ) |

Persistence of symptoms ( N ) |

Worsening of symptoms ( N ) |

||

|

≤ 60 d |

26 |

9 |

24 |

0.0052 |

|

> 60 d |

12 |

15 |

41 |

|

|

Diagnosis of first doctor consulted |

||||

|

Correctly diagnosed ( N ) |

Misdiagnosed ( N ) |

No diagnosis ( N ) |

||

|

≤ 60 d |

35 |

15 |

9 |

0.0062 |

|

> 60 d |

22 |

34 |

12 |

|

|

Number of different health services utilized before final diagnosis |

||||

|

0–1 ( N ) |

2–3 ( N ) |

≥ 4 ( N ) |

||

|

≤ 60 d |

18 |

37 |

4 |

0.0361[b] |

|

> 60 d |

13 |

43 |

12 |

|

Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; IQR, interquartile range; n, total participants; N, number of participants.

Note: Significant p-values are highlighted.

a Ayurveda or homeopathy.

b p-Value of chi-square for trend.

Discussion

Future Prospects

Reducing the diagnostic interval could result in patients coming to medical attention earlier, potentially improving outcomes. Our study observed that not all educated patients sought help early, and similarly, not all patients with limited or no education presented at advanced stages. Thus, reflecting that knowledge alone is insufficient for promoting timely help- seeking. It is therefore crucial to address barriers to accessing medical care and here efforts at both the patient and provider levels are required. The study findings have important implications for clinical practice, policy, and public health interventions aimed at reducing diagnostic delays in cancer. Strategies to address disparities in health care access, improve health literacy, and enhance awareness of cancer symptoms are essential for facilitating early detection and timely diagnosis. Additionally, initiatives to strengthen primary care, streamline referral pathways, and expedite diagnostic testing are crucial for minimizing delays and improving patient outcomes. Efforts to improve health education and awareness among this demographic group are vital for facilitating early detection and prompt referral for diagnostic evaluation.

Limitations

The cross-sectional study conducted in rural Western Maharashtra, India, offers crucial insights into the complex landscape of cancer care in India, highlighting areas for targeted interventions and policy reforms to improve diagnostic timeliness and treatment outcomes. While the research provides significant findings, it is not without limitations. First, the study's reliance on self-reported data from patients or caregivers introduces potential recall bias, affecting the accuracy and reliability of the reported diagnostic and treatment intervals. Additionally, the study was conducted at a tertiary cancer hospital located in a rural part of Western Maharashtra, which may not be representative of the entire population. Patients seeking care at such specialized facilities may differ from those who do not, potentially introducing sampling bias. Finally, the study's focus on a rural tertiary cancer hospital may not fully capture the experiences and challenges faced by individuals accessing cancer care in urban or other health care settings.

Strengths

The strengths of this study lie in its comprehensive approach to identifying and quantifying barriers to timely cancer diagnosis and treatment in a rural setting, thus offering a holistic understanding of the challenges faced by patients throughout their cancer care journey.

Conducted at a tertiary cancer hospital, the study offers valuable insights into the real-world challenges faced by cancer patients in Western Maharashtra, an area that has received limited research attention. The study's focus on a rural population highlights specific regional barriers, contributing to the broader discourse on health care disparities in low-resource settings. Additionally, by identifying significant associations between diagnostic delays and factors such as rural residence and initial health care consultation type, the study provides actionable data for policymakers and health care providers to address and mitigate these delays. This focus on both patient- and system-level factors accentuates the multifaceted nature of cancer care delays and the need for targeted interventions. Overall, the study's findings have noteworthy implications for improving cancer care delivery, enhancing early detection, and streamlining diagnostic and treatment processes in resource-limited settings.

Conclusion

The study highlights significant barriers in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer in Western Maharashtra, India. The median diagnostic and treatment intervals indicate substantial delays, particularly influenced by factors such as rural residency and the type of initial health care service utilized. The findings highlight the critical need for enhanced awareness, better access to health care services, and streamlined diagnostic processes to improve cancer care outcomes. Overcoming these barriers through targeted strategies can potentially reduce diagnostic delays and improve timely treatment initiation, ultimately enhancing the survival rates and quality of life for cancer patients. This study serves as a call to action for health care policymakers and practitioners to prioritize and address the challenges in cancer care, thereby improving the outcomes for patients in rural Western Maharashtra.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Authors' Contributions

1. A.N.:

- Concept: Contributed to the initial idea and framework of the study.

- Design: Helped design the study methodology.

- Intellectual Content: Provided key insights and intellectual content throughout the study.

- Literature Search: Conducted a comprehensive literature review to support the study's background and rationale.

- Clinical Studies: Coordinated and supervised the data collection for the study.

- Data Analysis: Participated in the interpretation of the data.

- Statistical Analysis: Assisted in performing the statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed significantly to the writing of the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed and approved the final manuscript before submission.

2. K.V.:

- Concept: Contributed to the development of the study concept.

- Design: Assisted in the design of the study methodology.

- Literature Search: Assisted with the literature review.

- Data Acquisition: Collected data from clinical sources.

- Data Analysis: Assisted in data interpretation.

- Statistical Analysis: Helped with statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Assisted in writing the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Helped with manuscript revisions.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed the manuscript draft.

3. G.R.N.:

- Concept: Provided input on the study concept.

- Design: Assisted with study design.

- Intellectual Content: Contributed to the intellectual content of the study.

- Literature Search: Participated in the literature search.

- Clinical Studies: Involved in clinical data collection.

- Data Acquisition: Contributed to data collection efforts.

- Statistical Analysis: Participated in the statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed to drafting the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Assisted with manuscript editing.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript.

4. S.R.:

- Concept: Helped refine the study concept.

- Design: Contributed to the study design.

- Literature Search: Assisted in gathering relevant literature.

- Data Acquisition: Assisted in data acquisition.

- Data Analysis: Helped analyze the data.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed to manuscript writing.

- Manuscript Editing: Assisted with revisions.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed the manuscript.

5. A.R.:

- Concept: Contributed to the conceptual framework.

- Design: Assisted in designing the study.

- Literature Search: Helped with the literature review.

- Data Acquisition: Participated in data collection.

- Data Analysis: Assisted in interpreting the data.

- Manuscript Preparation: Contributed to drafting sections of the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Helped edit the manuscript.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed the manuscript draft.

6. D.M.:

- Concept: Provided input on the initial concept.

- Design: Assisted in the study design.

- Literature Search: Participated in the literature search.

- Data Acquisition: Assisted in gathering data.

- Statistical Analysis: Contributed to the statistical analysis.

- Manuscript Preparation: Helped write the manuscript.

- Manuscript Editing: Assisted with editing the manuscript.

- Manuscript Review: Reviewed and approved the final draft.

Patient Consent

Patient consent is not required.

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. 2023 . Accessed May 7, 2024 at: https://www.who.int/newsroom/factsheets/detail/noncommunicablediseases

- National Health Mission. National Programme for Prevention and Control of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases & stroke (NPCDCS). New Delhi: NHM, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Accessed May 6, 2024 at: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=1048&lid=604

- Dillinger K. Global cancer cases will jump 77% by 2050, WHO report estimates. CNN Health. 2024 . Accessed May 6, 2024 at: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/02/02/health/who-cancer-estimates/index.html

- Indian Council of Medical Research & National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. A decade of research: impacting NCD public health actions 2022. ICMR- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. 2022 . Accessed May 6, 2024 at: https://ncdirindia.org/All_Reports/Monograph_2022/ICMR_NCDIR_Monograph.pdf

- National Health Mission. National Cancer Control Programme. New Delhi: NHM, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2005 . Accessed May 7, 2024 at: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/4249985666nccp_0.pdf

- Ramani VK, Jayanna K, Naik R. A commentary on cancer prevention and control in India: priorities for realizing SDGs. Health Sci Rep 2023; 6 (02) e1126

- Innovative Partnership for Action Against Cancer. Lack of awareness is a major barrier to early cancer detection. IPAA Cancer Foundation. 2019 . Accessed May 7, 2024 at: https://www.ipaac.eu/news-detail/en/24-lack-of-awareness-is-a-major-barrier-to- early-cancer-detection/

- Gulzar F, Akhtar MS, Sadiq R, Bashir S, Jamil S, Baig SM. Identifying the reasons for delayed presentation of Pakistani breast cancer patients at a tertiary care hospital. Cancer Manag Res 2019; 11: 1087-1096

- Hansen RP, Olesen F, Sørensen HT, Sokolowski I, Søndergaard J. Socioeconomic patient characteristics predict delay in cancer diagnosis: a Danish cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8: 49

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. India fact sheet. Global Cancer Observatory. 2021 . Accessed May 19, 2024 at: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/356-india-fact- sheet.pdf

- Khan MA, Hanif S, Iqbal S, Shahzad MF, Shafique S, Khan MT. Presentation delay in breast cancer patients and its association with sociodemographic factors in North Pakistan. Chin J Cancer Res 2015; 27 (03) 288-293

- Pakseresht S, Ingle GK, Garg S, Sarafraz N. Stage at diagnosis and delay in seeking medical care among women with breast cancer, Delhi, India. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014; 16 (12) e14490

- Gyenwali D, Khanal G, Paudel R, Amatya A, Pariyar J, Onta SR. Estimates of delays in diagnosis of cervical cancer in Nepal. BMC Womens Health 2014; 14 (01) 29

- Sachdeva R, Sachdeva S. Delay in diagnosis amongst carcinoma lung patients presenting at a tertiary respiratory centre. Clin Cancer Investig J 2014; 3: 288-292

- Wahls TL, Peleg I. Patient- and system-related barriers for the earlier diagnosis of colorectal cancer. BMC Fam Pract 2009; 10: 65

- Mitchell E, Macdonald S, Campbell NC, Weller D, Macleod U. Influences on pre-hospital delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer 2008; 98 (01) 60-70

- Macdonald S, Macleod U, Campbell NC, Weller D, Mitchell E. Systematic review of factors influencing patient and practitioner delay in diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Cancer 2006; 94 (09) 1272-1280

- Simon AE, Waller J, Robb K, Wardle J. Patient delay in presentation of possible cancer symptoms: the contribution of knowledge and attitudes in a population sample from the United Kingdom. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19 (09) 2272-2277

- Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, Macdonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer 2009; 101 (suppl 2, suppl 2): S92-S101

- Hansen RP, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Søndergaard J, Olesen F. General practitioner characteristics and delay in cancer diagnosis. a population-based cohort study. BMC Fam Pract 2011; 12: 100

- Krishnatreya M, Kataki AC, Sharma JD. et al. Educational levels and delays in start of treatment for head and neck cancers in North-East India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014; 15 (24) 10867-10869

- Sharma G, Gupta S, Gupta A. et al. Identification of factors influencing delayed presentation of cancer patients. Int J Community Med Public Health 2020; 7: 1705-1710

- Vidhya K, Gupta S, Lekshmi R. et al. Assessment of patient's knowledge, attitude, and beliefs about cancer: an institute-based study. J Educ Health Promot 2022; 11: 49

- Cotache-Condor C, Rice HE, Schroeder K. et al. Delays in cancer care for children in low-income and middle-income countries: development of a composite vulnerability index. Lancet Glob Health 2023; 11 (04) e505-e515

- Lombe DC, Mwamba M, Msadabwe S. et al. Delays in seeking, reaching and access to quality cancer care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2023; 13 (04) e067715

- Gopika MG, Prabhu PR, Thulaseedharan JV. Status of cancer screening in India: An alarm signal from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5). J Family Med Prim Care 2022; 11 (11) 7303-7307

- Apollo Health of the Nation. 2024. Apollo Hospitals. 2024 . Accessed May 21, 2024 at: https://www.apollohospitals.com/apollo_pdf/Apollo-Health-of-the-Nation-2024.pdf

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

24 February 2025

© 2025. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Study of socio‑demographic determinants of esophageal cancer at a tertiary care teaching hospital of Western Maharashtra, IndiaPurushottam A. Giri, South Asian Journal of Cancer, 2014

- In response to “Telemedicine: An Era Yet to Flourish in India”Neeraj Kumar, Annals of the National Academy of Medical Sciences (India)

- In response to “Telemedicine: An Era Yet to Flourish in India”Neeraj Kumar, VCOT Open

- Quality of Life of Primary Caregivers Attending a Rural Cancer Centre in Western Maharashtra: A Cross-Sectional StudyShubham S. Kulkarni, Indian J Radiol Imaging, 2021

- Financial Burden Faced by Families due to Out‑of‑pocket Expenses during the Treatment of their Cancer Children: An Indian PerspectiveLatha M Sneha, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2017

- Factors Influencing the Adoption of Telemedicine for Treatment of Military Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress DisorderKruse, Clemens Scott, Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine

- Perceptions of Young Adult Central Nervous System Cancer Survivors and Their Parents Regarding Career Development and EmploymentDavid R. Strauser, Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education, 2014

- Relevance and Completeness of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Comprehensive Breast Cancer Core Set: the Patient Per...Khan, Fary, Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine

- The social and cultural consequences of infertility in rural and peri-urban Malawi<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

</svg> Kristan Elwell, African Journal of Reproductive Health, 2022 - Chapter 10 Smoking Cessation Interventions in Cancer Care: Opportunities for Oncology Nurses and Nurse ScientistsMary E. Cooley, Annu Rev Nurs Res, 2009

Fig 1: Barriers to diagnosis and treatment.

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. 2023 . Accessed May 7, 2024 at: https://www.who.int/newsroom/factsheets/detail/noncommunicablediseases

- National Health Mission. National Programme for Prevention and Control of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases & stroke (NPCDCS). New Delhi: NHM, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Accessed May 6, 2024 at: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=1048&lid=604

- Dillinger K. Global cancer cases will jump 77% by 2050, WHO report estimates. CNN Health. 2024 . Accessed May 6, 2024 at: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/02/02/health/who-cancer-estimates/index.html

- Indian Council of Medical Research & National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. A decade of research: impacting NCD public health actions 2022. ICMR- National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. 2022 . Accessed May 6, 2024 at: https://ncdirindia.org/All_Reports/Monograph_2022/ICMR_NCDIR_Monograph.pdf

- National Health Mission. National Cancer Control Programme. New Delhi: NHM, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2005 . Accessed May 7, 2024 at: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/4249985666nccp_0.pdf

- Ramani VK, Jayanna K, Naik R. A commentary on cancer prevention and control in India: priorities for realizing SDGs. Health Sci Rep 2023; 6 (02) e1126

- Innovative Partnership for Action Against Cancer. Lack of awareness is a major barrier to early cancer detection. IPAA Cancer Foundation. 2019 . Accessed May 7, 2024 at: https://www.ipaac.eu/news-detail/en/24-lack-of-awareness-is-a-major-barrier-to- early-cancer-detection/

- Gulzar F, Akhtar MS, Sadiq R, Bashir S, Jamil S, Baig SM. Identifying the reasons for delayed presentation of Pakistani breast cancer patients at a tertiary care hospital. Cancer Manag Res 2019; 11: 1087-1096

- Hansen RP, Olesen F, Sørensen HT, Sokolowski I, Søndergaard J. Socioeconomic patient characteristics predict delay in cancer diagnosis: a Danish cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8: 49

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. India fact sheet. Global Cancer Observatory. 2021 . Accessed May 19, 2024 at: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/356-india-fact- sheet.pdf

- Khan MA, Hanif S, Iqbal S, Shahzad MF, Shafique S, Khan MT. Presentation delay in breast cancer patients and its association with sociodemographic factors in North Pakistan. Chin J Cancer Res 2015; 27 (03) 288-293

- Pakseresht S, Ingle GK, Garg S, Sarafraz N. Stage at diagnosis and delay in seeking medical care among women with breast cancer, Delhi, India. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014; 16 (12) e14490

- Gyenwali D, Khanal G, Paudel R, Amatya A, Pariyar J, Onta SR. Estimates of delays in diagnosis of cervical cancer in Nepal. BMC Womens Health 2014; 14 (01) 29

- Sachdeva R, Sachdeva S. Delay in diagnosis amongst carcinoma lung patients presenting at a tertiary respiratory centre. Clin Cancer Investig J 2014; 3: 288-292

- Wahls TL, Peleg I. Patient- and system-related barriers for the earlier diagnosis of colorectal cancer. BMC Fam Pract 2009; 10: 65

- Mitchell E, Macdonald S, Campbell NC, Weller D, Macleod U. Influences on pre-hospital delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer 2008; 98 (01) 60-70

- Macdonald S, Macleod U, Campbell NC, Weller D, Mitchell E. Systematic review of factors influencing patient and practitioner delay in diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Cancer 2006; 94 (09) 1272-1280

- Simon AE, Waller J, Robb K, Wardle J. Patient delay in presentation of possible cancer symptoms: the contribution of knowledge and attitudes in a population sample from the United Kingdom. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19 (09) 2272-2277

- Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, Macdonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer 2009; 101 (suppl 2, suppl 2): S92-S101

- Hansen RP, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Søndergaard J, Olesen F. General practitioner characteristics and delay in cancer diagnosis. a population-based cohort study. BMC Fam Pract 2011; 12: 100

- Krishnatreya M, Kataki AC, Sharma JD. et al. Educational levels and delays in start of treatment for head and neck cancers in North-East India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014; 15 (24) 10867-10869

- Sharma G, Gupta S, Gupta A. et al. Identification of factors influencing delayed presentation of cancer patients. Int J Community Med Public Health 2020; 7: 1705-1710

- Vidhya K, Gupta S, Lekshmi R. et al. Assessment of patient's knowledge, attitude, and beliefs about cancer: an institute-based study. J Educ Health Promot 2022; 11: 49

- Cotache-Condor C, Rice HE, Schroeder K. et al. Delays in cancer care for children in low-income and middle-income countries: development of a composite vulnerability index. Lancet Glob Health 2023; 11 (04) e505-e515

- Lombe DC, Mwamba M, Msadabwe S. et al. Delays in seeking, reaching and access to quality cancer care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2023; 13 (04) e067715

- Gopika MG, Prabhu PR, Thulaseedharan JV. Status of cancer screening in India: An alarm signal from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5). J Family Med Prim Care 2022; 11 (11) 7303-7307

- Apollo Health of the Nation. 2024. Apollo Hospitals. 2024 . Accessed May 21, 2024 at: https://www.apollohospitals.com/apollo_pdf/Apollo-Health-of-the-Nation-2024.pdf

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share