Unilateral Interstitial Lung Disease with Contralateral Effusion: Unusual Case Report of Dasatinib Toxicity

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2022; 43(02): 216-222

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-1742334

Abstract

Dasatinib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) used in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). While pleural effusion due to Dasatinib is well described in the literature, interstitial lung disease (ILD) caused by it is rare. A 60-year-old gentleman was on treatment with 100 mg of tablet Dasatinib per day for chronic myeloid leukemia. He presented to the outpatient department with history of progressive breathlessness over 2 months. High-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) thorax revealed mild right-sided effusion and non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern of ILD in the left lower lobe. Thoracocentesis of the right-sided pleural effusion showed exudative and lymphocytic rich pleural effusion. The effusion was negative for malignant cells or infection. Biopsy of the left lower lobe was consistent with the diagnosis of ILD. He was started on prednisolone which was gradually tapered and stopped. At 3 months, there was a complete resolution of the ILD and pleural effusion. Clinicians need to be aware about the pleuroparenchymal toxicities of Dasatinib. Early diagnosis and treatment with steroids can lead to complete resolution of the signs and symptoms.

Declaration of Patient Consent

Patient consent is taken at the time of patient's registration at the Hospital for use of their anonymized data for research purpose.

Sources of Support

None.

Publication History

Article published online:

15 February 2022

© 2022. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Dasatinib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) used in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). While pleural effusion due to Dasatinib is well described in the literature, interstitial lung disease (ILD) caused by it is rare. A 60-year-old gentleman was on treatment with 100 mg of tablet Dasatinib per day for chronic myeloid leukemia. He presented to the outpatient department with history of progressive breathlessness over 2 months. High-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) thorax revealed mild right-sided effusion and non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern of ILD in the left lower lobe. Thoracocentesis of the right-sided pleural effusion showed exudative and lymphocytic rich pleural effusion. The effusion was negative for malignant cells or infection. Biopsy of the left lower lobe was consistent with the diagnosis of ILD. He was started on prednisolone which was gradually tapered and stopped. At 3 months, there was a complete resolution of the ILD and pleural effusion. Clinicians need to be aware about the pleuroparenchymal toxicities of Dasatinib. Early diagnosis and treatment with steroids can lead to complete resolution of the signs and symptoms.

Introduction

Dasatinib is an orally active tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) used as a second-line agent in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). It is 325 times more potent than the first-generation TKI, imatinib.[1] Like its predecessor, it inhibits the activities of BCR-ABL, c-kit, and PDGFR oncogenes. Also, it inhibits the activities of src (v-sarcoma) family kinases, tec, and Lyn oncogenes.1 Amongst the respiratory toxicities, pleural effusion is most common. Other pulmonary complications like interstitial lung disease (ILD), alveolar hemorrhage, pulmonary hypertension are rarely described in literature noticed on an average between 1 month and 25 months of therapy.[2] [3] [4] [5]

We report a case of concomitant and contralateral pleuropulmonary toxicity (ILD and pleural effusion) due to Dasatinib at 30 months after drug initiation.

Case Report

A 60-year-old gentleman, smoker, diagnosed with CML, was treated with 100 mg of Dasatinib daily. Patient was in CML biphenotypic blast crisis while starting Dasatinib therapy. The BCR/ABL Ph:t (9;22) report showed a signal pattern consistent with evidence of BCR-ABL fusion Ph:t(9;22) with 9q deletion in 190/200 (95%) of cells. Ph:t (9;22) was detected in 18/20 metaphase cells. He had no other documented comorbidities except hypothyroidism. Detailed smoking history and Sokal score were not available.

Thirty months after the initiation of therapy, he presented with complaints of progressive breathlessness over 2 months. On examination, he was afebrile, tachypneic at rest with a respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min and saturation of 92%-on room air. Fine end-inspiratory velcro crackles were appreciated in the left infrascapular area (ISA) with reduced breath sounds on the right ISA on auscultation. His leukocyte count was 4,800 cells/dL with 8%-myelocytes and 2%- metamyelocytes but no blast cells on peripheral smear. Hemoglobin was 12.4 g/dL and platelet count of 114,000/dL. The chest radiograph demonstrated reticular opacities in the left lower zone and a right-sided pleural effusion.

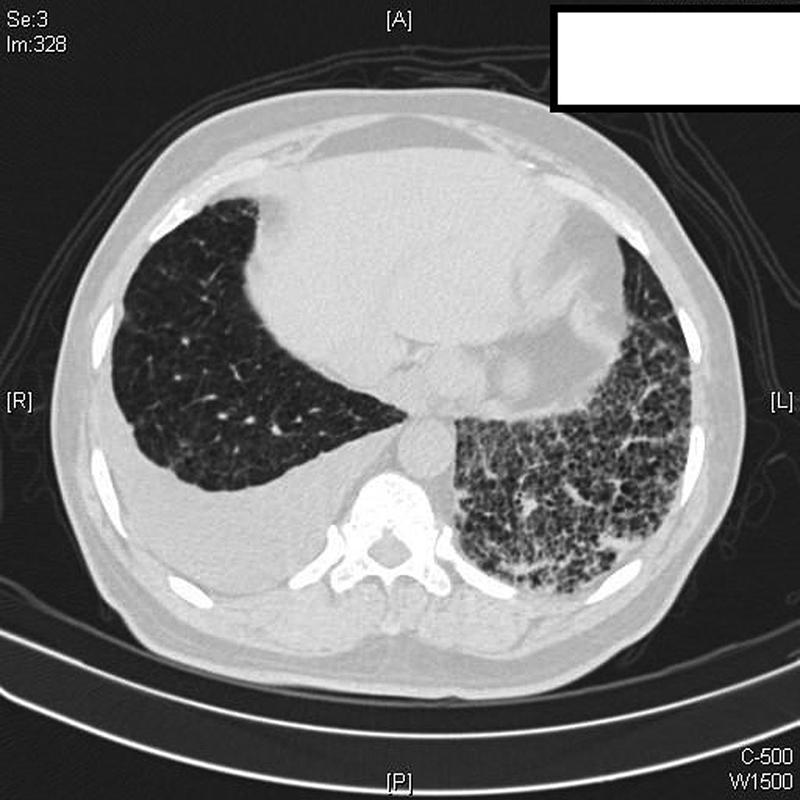

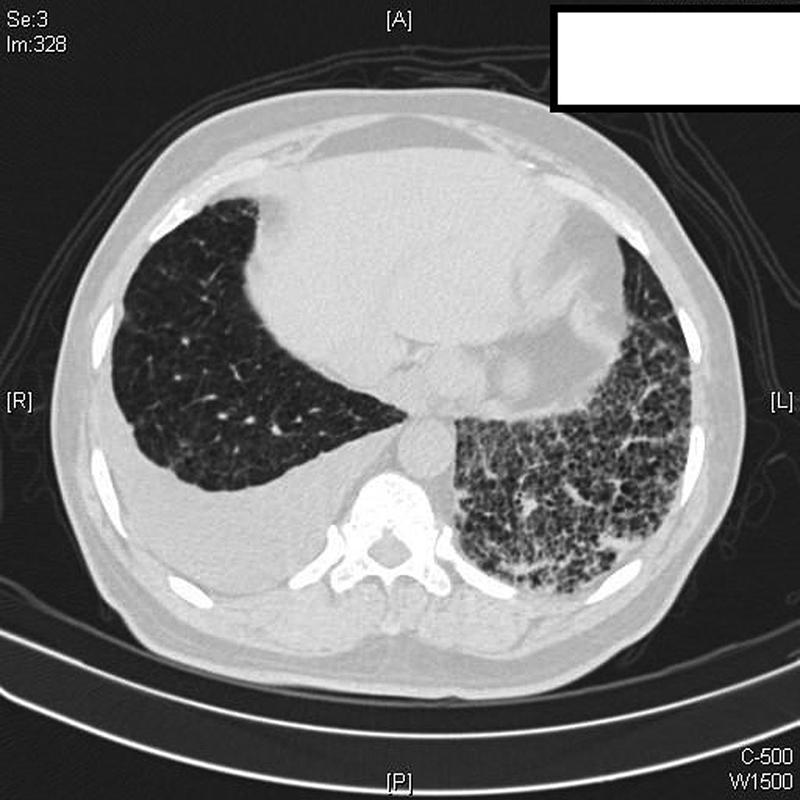

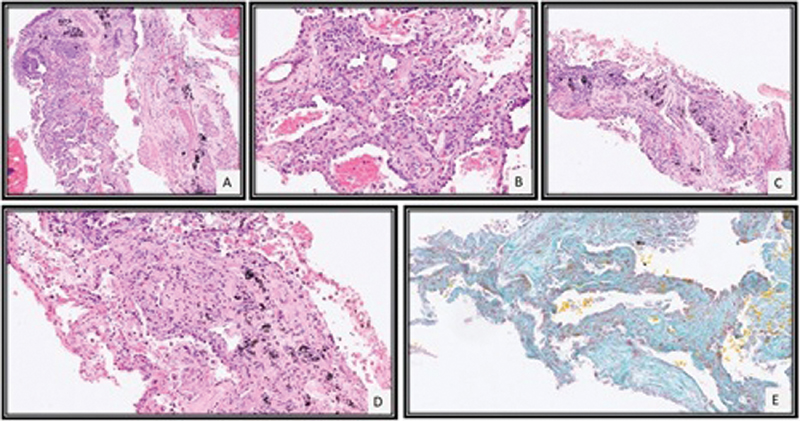

High-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) thorax ([Fig. 1]) revealed diffuse centrilobular emphysema, mild right-sided effusion and extensive reticular, interstitial septal thickening with ground-glass opacities and small patchy areas of consolidation in the left lower lobe favoring Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP) pattern. The pulmonary artery to aorta diameter was less than one. Two-dimensional echo showed a normal ejection fraction and no evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Diagnostic thoracentesis of the effusion showed an exudative, lymphocytic rich (91%) pleural effusion with low adenosine deaminase (ADA) (8 IU/L). The effusion cytology was negative for malignant cells. Cultures were negative for bacteria and fungi. Investigations for tuberculosis including Xpert MTB/Rif and cultures were negative as well. Pulmonary function testing revealed a moderate restriction (forced vital capacity [FVC]1,300 mL) in the lung capacity with severely reduced diffusion capacity (DLCO) of 36%. Rheumatological analyses like ANA, DsDNA, RA, anti-CCP, SSA, SSB, anti-Scl-70, and anti-Jo-1 were negative.

| Fig. 1High-resolution chest CT scan: interlobular septal thickening and ground-glass opacities in the left lower lobe along with right-sided pleural effusion on a background of centrilobular emphysema.

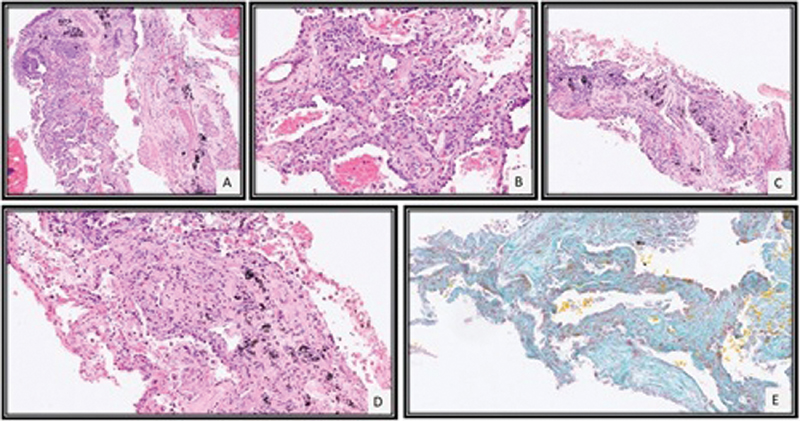

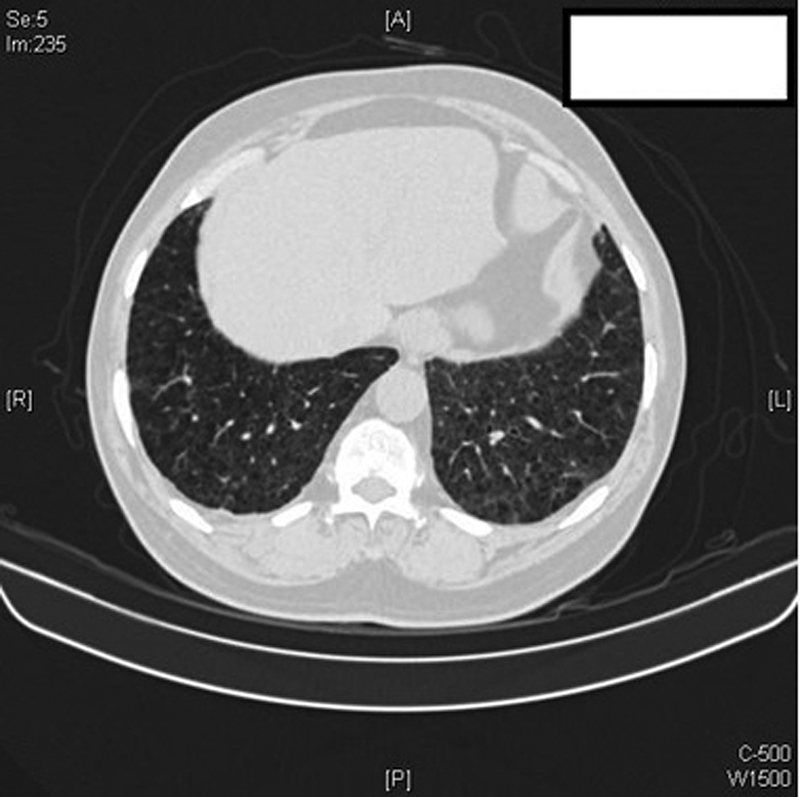

Image-guided biopsy of the left lower lobe showed focal interstitial lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, mild septal thickening, and fibrosis ([Fig. 2]). There was no evidence of infiltration by blast or myeloid precursors or granulomas. These features were consistent with NSIP like pattern of ILD.

| Fig.2:CT-guided lung biopsy revealed tissue core of alveolated lung parenchyma with mild interstitial lymphocytic inflammation (A), type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (B), and mild septal widening with fibrosis (C, D) which was highlighted by special stain for Masson Trichrome (E).

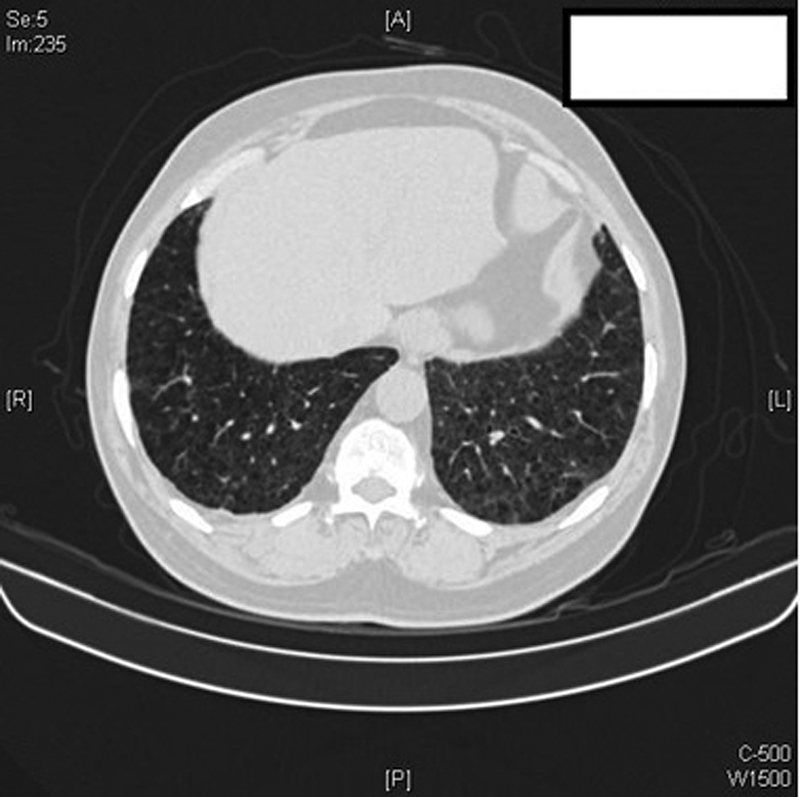

A diagnosis of Dasatinib toxicity was made and the drug was discontinued. The patient was treated with 40 mg prednisolone initially, tapered gradually and stopped. At the 3 months follow-up, the patient's resting room air saturation had improved to 98%, FVC increased by 600 mL (FVC 1,900 mL), which was within the normal range predicted for the patient with marginally improved diffusion capacity of 40%. HRCT thorax at 3 months revealed a complete resolution of ILD and effusion ([Fig. 3]). After Dasatinib discontinuation, patient was started on nilotinib 400 mg BD.

| Fig.3:High-resolution chest CT scan: significant clearing of left lower lobe interlobular septal thickening and ground-glass opacities with minimal residual right pleural thickening. Centrilobular emphysema is well appreciated here.

Discussion

Dasatinib is an orally active TKI, two logs more potent than its precursor, imatinib mesylate, and is indicated not only for imatinib resistant or intolerant cases of CML but also as a first-line option in CML, if clinically indicated.

Common hematological side effects of Dasatinib include myelosuppression with neutropenia and thrombocytopenia.[6] The significant cardiothoracic adverse effects are pleural and pericardial effusions.[7] Other side effects like pulmonary hypertension, alveolar hemorrhage, and ILD are rare in literature[3] [4] [5] [8] with most studies reporting an incidence of pleural effusion at 23 to 35% ([Table 1]). Summary of important studies of Dasatinib-induced pleural effusion is described in [Table 1].

|

Publication |

Total cases |

Pleural effusion no. (percentage) |

Median time for development of effusion (mo) |

Median dose |

Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Iurlo et al[16] |

853 |

196 (23%) |

16.6 |

100 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Cortes et al[17] |

259 |

73 (28%) |

30 |

100 mg/d |

Stoppage diuretic, steroid |

|

Shah et al[18] |

670 |

220 (34%) |

24 |

100 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Hagihara et al[19] |

52 |

17 (33%) |

9 |

100 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Kantarjian et al[20] |

316 |

93 (29%) |

15 |

70–140 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Kim et al[21] |

34 |

10 (25%) |

– |

100 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Cortes et al[22] |

157 |

45 (28%) |

2.4–3 |

140 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Apperley et al[23] |

174 |

47 (27%) |

4 |

140 mg/d |

Stoppage diuretic, steroid |

|

Hochhaus et al[24] |

387 |

106 (27%) |

– |

140–180 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Suh et al[11] |

81 |

28 (35%) |

6.3 |

100–140 mg/d |

Stoppage |

|

Fox et al[25] |

212 |

53 (25%) |

11 |

100 mg/d |

Stoppage diuretic, steroid |

|

Study |

Patient no. |

Symptoms |

Time interval (days) |

HRCT chest findings |

Other findings |

Treatment |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1.Bergeron et al[8] |

1 |

Dyspnea, cough |

256 |

Bibasilar GGO Right pleural effusion |

Exudate and lymphocyte rich pleural fluid |

Drug interruption and reintroduction at 80 mg/d (low dose) |

Resolution and no relapse after reintroduction |

|

2 |

Dyspnea, cough, myalgia |

29 |

Diffuse GGO |

– |

Drug interruption |

Resolution |

|

|

3 |

Chest pain |

463 |

Bibasilar septal thickening |

– |

Drug interruption and reintroduction at 80 mg/d (low dose) |

Resolution and no relapse after reintroduction |

|

|

4 |

Dyspnea, fever |

87 |

Bibasilar septal thickening, right pleural effusion, and left-sided consolidation |

Exudate and lymphocyte rich pleural fluid. Marked lymphocytic infiltration in surgical lung biopsy |

Drug interruption |

Resolution |

|

|

5 |

Dyspnea, cough and fever |

216 |

Mosaic pattern |

– |

Prednisone @ 1 mg/kg/d and tapered over 2 mo |

Resolution |

|

|

6 |

Cough |

500 |

Bibasilar GGO and septal thickening with right pleural effusion |

Exudate and lymphocyte rich pleural fluid |

Drug interruption and reintroduction at 80 mg/d (low dose) |

Resolution and no relapse after reintroduction |

|

|

7 |

Dyspnea, cough and chest pain |

33 |

Bilateral pleural effusion and left lower lobe GGO |

Exudate and neutrophil rich pleural fluid |

Drug interruption and reintroduction at 80 mg/d (low dose). |

Resolution but relapse after reintroduction |

|

|

2.Radaelli et al[3] |

1 |

Fever, dyspnea, |

27 |

Bilateral GGO and bilateral pleural effusion |

– |

Drug interruption with methyl prednisone @ 40 mg/d tapered over 1 mo |

Resolution |

|

3.Sakoda et al[2] |

1 |

Cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea |

365 |

Bilateral GGO with crazy paving pattern |

– |

Drug interruption and pulse methyl prednisone @ 1 g/d × 3 d and tapered over 1 mo |

Resolution |

|

4.Jasielec and Larson[4] |

1 |

Cough, fever, and dyspnea |

Several days (not specified) |

Bilateral GGO in middle and upper lobes |

Transbronchial biopsy showed non-specific focal lymphocytic aggregates |

Drug interruption and pulse methyl prednisone @ 1 g/d × 3 d and tapered over 1 mo |

Resolution |

|

5. Sato et al[12] |

1 |

Dyspnea |

730 |

Bilateral effusion with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates |

Transbronchial biopsy showed organizing pneumonia pattern |

Drug interruption and treatment with corticosteroid (dose not known) |

Resolution |

| Fig. 1High-resolution chest CT scan: interlobular septal thickening and ground-glass opacities in the left lower lobe along with right-sided pleural effusion on a background of centrilobular emphysema.

| Fig.2:CT-guided lung biopsy revealed tissue core of alveolated lung parenchyma with mild interstitial lymphocytic inflammation (A), type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (B), and mild septal widening with fibrosis (C, D) which was highlighted by special stain for Masson Trichrome (E).

| Fig.3:High-resolution chest CT scan: significant clearing of left lower lobe interlobular septal thickening and ground-glass opacities with minimal residual right pleural thickening. Centrilobular emphysema is well appreciated here.

References

- Nam S, Kim D, Cheng JQ. et al. Action of the Src family kinase inhibitor, dasatinib (BMS-354825), on human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 2005; 65 (20) 9185-9189

- Sakoda Y, Arimori Y, Ueno M, Matsumoto T. A suspected case of an alveolar haemorrhage caused by Dasatinib. Intern Med 2017; 56 (02) 203-206

- Radaelli F, Bramanti S, Fantini NN, Fabio G, Greco I, Lambertenghi-Deliliers G. Dasatinib-related alveolar pneumonia responsive to corticosteroids. Leuk Lymphoma 2006; 47 (06) 1180-1181

- Jasielec JK, Larson RA. Dasatinib-related pulmonary toxicity mimicking an atypical infection. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34 (06) e46-e48

- Montani D, Bergot E, Günther S. et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients treated by Dasatinib. Circulation 2012; 125 (17) 2128-2137

- Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H. et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med 2006; 354 (24) 2531-2541

- Quintás-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, O'brien S. et al. Pleural effusion in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with Dasatinib after imatinib failure. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25 (25) 3908-3914

- Bergeron A, Réa D, Levy V. et al. Lung abnormalities after Dasatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia: a case series. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 176 (08) 814-818

- Qiu Z-Y, Xu W, Li J-Y. Large granular lymphocytosis during Dasatinib therapy. Cancer Biol Ther 2014; 15 (03) 247-255

- Nagata Y, Ohashi K, Fukuda S, Kamata N, Akiyama H, Sakamaki H. Clinical features of dasatinib-induced large granular lymphocytosis and pleural effusion. Int J Hematol 2010; 91 (05) 799-807

- Suh KJ, Lee JY, Shin D-Y. et al. Analysis of adverse events associated with Dasatinib and nilotinib treatments in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients outside clinical trials. Int J Hematol 2017; 106 (02) 229-239

- Sato M, Watanabe S, Aoki N. et al. A case of drug-induced organizing pneumonia caused by Dasatinib. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2018; 45 (05) 851-854

- Zitnik RJ, Matthay RA. Drug-Induced Lung Disease. 3rd ed. Interstitial Lung Disease. Hamilton, Ontario: Mosby Yearbook; 1998

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). 2017 . Available at: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/templates_applications.htm

- Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V. et al; INBUILD Trial Investigators. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N Engl J Med 2019; 381 (18) 1718-1727

- Iurlo A, Galimberti S, Abruzzese E. et al. Pleural effusion and molecular response in Dasatinib-treated chronic myeloid leukemia patients in a real-life Italian multicenter series. Ann Hematol 2018; 97 (01) 95-100

- Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM. et al. Final 5-year study results of DASISION: the Dasatinib versus imatinib study in Treatment-Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34 (20) 2333-2340

- Shah NP, Rousselot P, Schiffer C. et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic-phase, chronic myeloid leukemia patients: 7-year follow-up of study CA180-034. Am J Hematol 2016; 91 (09) 869-874

- Hagihara M, Iriyama N, Yoshida C. et al. Association of pleural effusion with an early molecular response in patients with newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia receiving Dasatinib: results of a D-First study. Oncol Rep 2016; 36 (05) 2976-2982

- Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Kim D-W. et al. Phase 3 study of Dasatinib 140 mg once daily versus 70 mg twice daily in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase resistant or intolerant to imatinib: 15-month median follow-up. Blood 2009; 113 (25) 6322-6329

- Kim D-W, Saussele S, Williams LA. et al. Outcomes of switching to Dasatinib after imatinib-related low-grade adverse events in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: the DASPERSE study. Ann Hematol 2018; 97 (08) 1357-1367

- Cortes J, Kim D-W, Raffoux E. et al. Efficacy and safety of Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant or -intolerant patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in blast phase. Leukemia 2008; 22 (12) 2176-2183

- Apperley JF, Cortes JE, Kim D-W. et al. Dasatinib in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase after imatinib failure: the START of a trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27 (21) 3472-3479

- Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Deininger M. et al. Dasatinib induces durable cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Leukemia 2008; 22 (06) 1200-1206

- Fox LC, Cummins KD, Costello B. et al. The incidence and natural history of Dasatinib complications in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv 2017; 1 (13) 802-811

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share